The first time I stood in the presence of the 1927 Probat Perfekt roaster at Panther Coffee‘s Miami headquarters, it set my imagination alight. I had traveled there on the suggestion of a friend, merely hoping to experience the coffee and scope out the well-regarded shop and roastery. It must have looked strange when I darted away from my place in the middle of a long line of customers upon catching a glimpse of the Perfekt, a storied and prized machine in coffee roasting circles.

As someone who has roasted on Probats of various ages and sizes, these old machines appeal to me professionally as well as personally. And as an amateur historian, an interwar Perfekt was a marvelous discovery. Conceived at the tip of an engineer’s pen and cast from a factory’s mold, it has endured an unknowable number of relocations, and persevered through two world wars and the collapses of empires.

What went into building this behemoth, this coffee-roasting colossus? After years contemplating this question and finally standing face-to-face with the Perfekt, I set out for answers. What I discovered was the story of a humble casting facility on the banks of the Rhine River that, through plenty of innovation and adversity, would achieve mastery in the manufacture of coffee roasters.

My search began with an email in poorly constructed German to an industrial museum in Mannheim. “No, we do not have any manuals or documents for that machine,” was the reply. Perhaps Probat itself then? An equally poor email in German was answered by the PR and museum team. Tina Abbing and Iris Gerlach answered a string of questions and offered to dig into their archive. This time the results were encouraging. Advertisements, archived manuals and documents dating into the early 1900s allowed the search to begin. Attaining these documents led to an obscure and out-of-print book, and another email to the same industrial museum in Mannheim. Three months later, after hitting these walls, a confused librarian in Seattle called asking where to send a library loan from Germany. It was game on.

The 19th century was an extraordinary time, fraught with conflict and diplomacy as Germany carved its place into the fabric of great industrial nations. With this tumultuous backdrop, the Emmericher Maschinenfabrik & EisengieBerei company was founded in 1868, in Emmerich, Germany. Its founders, Alex van Gulpen, Johann Heinrich Lensing and Theodor von Gimborn, saw the task of roasting coffee as a dirty and difficult one that was nevertheless crucial to the provision of this universally savored beverage. By the late 1870s, Emmericher Maschinenfabrik had produced various metal products and other items of coffee equipment before Gimborn, an engineer, struck upon the design for its first commercially successful coffee roaster. It was the spark that would ignite a roaster empire: The Emmerich Spherical Coffee Roaster.

“671 units for 1880” was what Theodor von Gimborn recorded frankly in his log. “Thus 56 units per month.” The matter-of-factness of this report masks what was in truth a gargantuan success. Letters to the company from happy clients reveal the impact their machine was making in the coffee world, including praise for its wonderfully even roast, and feedback that customers would “only purchase coffee roasted on a machine from Emmerich.” The factory had created a viable and beloved product, and with sound financial footing they set off at a sprint to keep pace with demand.

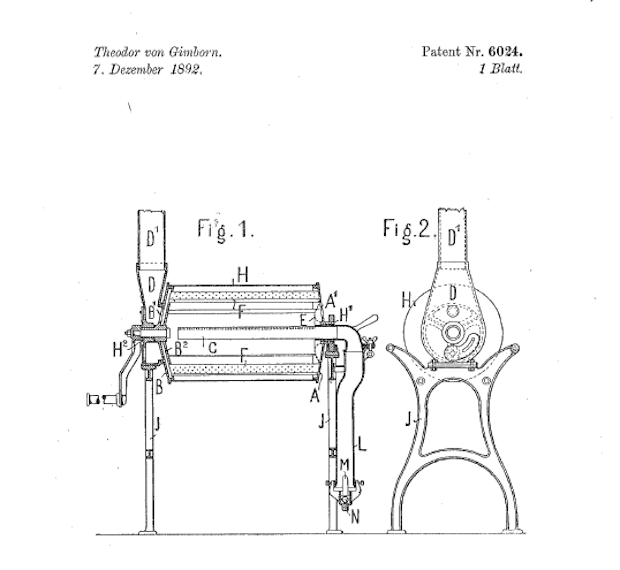

Competition from within the growing industry, spurred by the forces of industrialization, forced the proto-Probat company to improve, adapt and eventually move beyond its successful spherical roaster. Rapid revolutions of design yielded plenty of impractical ideas, as patent records from the late 1880s to the early 1900s show a series innovations that failed to reap commercial success. Various trier designs, heat shields and electrical heating systems were tested and abandoned. Improved gearing systems and electric belt drives were implemented. In the hope of tracing Probat’s progress in the era, I poured through the piles of patents that were issued and bought at a rapid pace throughout Germany at the time.

In the tangled morass of design and technical jargon, through an obscure database in a dusty corner of the German government’s files, my eyes fell upon a description matching that of an old friend. “With solid walled drum…” it began. Unfolding in a series of documents from around the turn of the 20th century was the Perfekt roaster, an industrial mammoth compared to the spherical roaster that preceded it. Extravagantly mechanical, with belts, levers and gears exposed, it was a hulking marvel of ingenuity that, when contextualized from our perspective today, cast a sort of menacing foreshadow. It was fortified with impenetrable metal, whirring with obedient precision and harnessing the power of heat and flame — all these benign boons to the field of coffee roasting would soon be substantially less benign on the fields of battle.

History books documenting The Great War and the heavy years that it engulfed the whole of Europe tend not to dwell much on the coffee industry’s experience, specifically. What’s known is that Emmericher Maschinenfabrik co-founder Theodor von Gimborn died in 1916. Patent submissions, meanwhile, slowed to a crawl across the German Empire during that era. Information concerning roaster production was either lost in the general post-war tumult, or in the shuffle of the factory being conscripted for the production of war materials, stymied as it was by the Allied blockade.

Despite generous research and assistance from Probat’s own museum in Emmerich, the paper trail is sparse for the period of a defeated Germany’s transition into the Weimar Republic. It is at least known that the factory survived. In fact it hummed right along, despite occupying forces stationed just across the river. By the dawn of the 1920s, the name “Probat” became the imprint on the roasters, and the factory floor was abuzz once again, hard at the task of producing coffee roasters.

Advertisements and marketing materials from the Netherlands around 1921 indicate that production ramped up in the post-war years. With trade, demand, and competition on the rise internationally, Probat needed to adapt in order to remain an international power. The pressure was on from manufacturers in the United States, and so by purchasing patents, inventing new mechanisms, and upgrading previous designs with newer technology, Probat took a major stride forward with the Probat G Series roaster, so named for the word “groß” which in German means large or great. The G Series hit the market in 1930.

This machine will look familiar to those that roast on newer Probats today. Sadly, its production ground suddenly to a halt, and not by market-driven forces. The factory in Emmerich was exceedingly lucky throughout most of the Second World War, continuing to produce fine roasting machines while battles raged on both fronts a safe distance away. Yet when the war finally reached Emmerich, it did so with a vengeance.

On October 7, 1944, a squadron of 11 Lancaster Heavy Bombers left England bound for Emmerich. By this point the city had endured other bombings, though the factory still stood. Flak brought down one bomber, but the remaining 10 dropped their payloads on the remaining targets in Emmerich, including the factory. It was a complete ruination, save for a single standing smokestack. In a skirmish a few months later in 1945, the smoldering smokestack was feared to hold a sniper. Canadian Platoon Commander J.W. Keith reported, “Our artillery gave it some attention and knocked the top off. This was the final bit of destruction.”

The scene near the original Emmericher Maschinenfabrik factory. It is unknown whether the factory site is visible within this photo.

All of Europe, and Probat, too, needed to rebuild. The factory was indeed rebuilt and the brand charged forward. Like the rest of West Germany, Probat speedily rose from its own smoking ruins with intense focus on the quality of its engineering and manufacturing processes. By 1950, Probat’s exports surpassed its domestic sales, and the renowned, coveted G and UG series roasters leaving the factory were arguably among the best they’d ever produced. Maybe necessity was the mother of reinvention, or maybe Probat’s post-war triumph is pure testimony to both the dedication of a company passionate about its product and to the resilience of the human spirit overall. Maybe it’s a little of all three. Either way, the reconstructed brand continued to push forward, shipping world-class and universally admired machines everywhere from Australia to Alaska by 1959.

Now formally called Probat-Werke, the maker of these seemingly immortal machines remains a manufacturing pillar in the coffee industry. Probats from every era continue to transform unassuming greens into the invigorating coffees at the hands of skilled artisans, and it is humbling to consider the many lives that have, in ways big and small, been affected by these machines — The owners, of course, but also the generations of workers who built them, the farmers that grew the coffee purchased to be roasted in them, the untold millions of regular people who enjoyed the resulting brews. The 1927 Perfekt roaster I continue to admire at Panther Coffee in Miami is more than just a machine, and more than just an artifact. It is a living, breathing monument to the generations of people all around the world whose lives converge at the turn of that drum.

Andrew Russo

Andrew Russo is the Coffee and Strategy Specialist at Catalyst Coffee Consulting.

Comment