The birth of American coffee. Today we have green coffee extracts pitched for weight loss, butter coffee pitched as a physical neurological booster, tenuous claims about the significance of “washed” coffee and all kinds of pseudoscientific hooey in the marketing of new coffee products.

In a piece on “the birth of American coffee,” Ozy reminds us that the industry has had its fare share of questionable science in marketing from the outset. But did you also know that the U.S. had a National Coffee Roasters Association? And that in one of the first ever truly scientific explorations in coffee quality, that association commissioned MIT researchers to come up with a recipe for the perfect cup? Here’s more from the must-read Ozy piece:

Wanted: someone to set the record straight on coffee’s health effects and work out the recipe for a perfect cup.

This was the National Coffee Roasters Association’s proposition to Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Samuel Prescott in 1920, in exchange for $40,000 worth of funding (half a million today). The public was fed up with snake-oil-style health ads and were newly protected from fraudulent pseudo-medical packaging by legislation. So coffee peddlers needed more precise, scientific advertising — and nothing embodied precision like MIT.

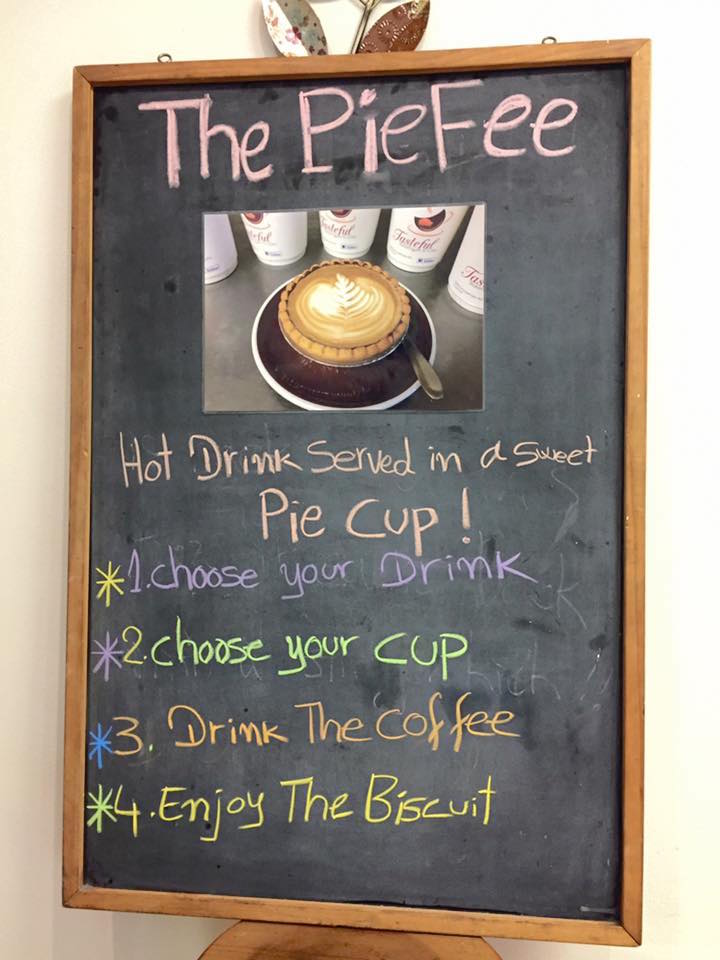

Put more coffee in ridiculous vessels. It’s just good business these days. Last month, the New Zealand café Tasteful Bakehouse posted a photo of a “Piefee,” involving a small pie crust with a chocolate liner filled with some combination of coffee and steamed milk. Naturally, like all coffee served in edible vessels, it became a sensation. To the credit of Tasteful Bakehouse and Piefee creator Chamnan Ly, the conconction seems infinitely more delicious than, say, the avo-latte, or even a tomato cortado. In a piece last week with SmartCompany, marketing expert Michelle Gamble says as retailers we ought to expect more goofy offerings like this:

“Everyone is going to try and reinvent food ideas, it’s just beginning. We’re nowhere near the peak,” Gamble says.

She later adds:

“Customers want to be entertained in all of our retail experiences, and businesses have got to make it exciting for them when they can. It’s easier than ever to do things in your home now, so it’s about getting people to act and creating more of an experience.”

Starbucks Irish franchisees have purchased an iconic coffee kiosk in Dublin. The Irish Times reported that brothers Colum and Ciarán Butler bought the hexagonal kiosk — which has served for decades as a high-foot-traffic coffee spot for commuters — at the intersection of Lansdowne, Pembroke and Northumberland roads:

The Butlers outbid several other investors for the tiny premises, paying €330,000 for what is possibly one of the most expensive commercial properties in the city.

The tiny floor area, a mere 37sq ft, works out to €8,918/sq ft even before purchasing costs are taken into consideration. But the kiosk’s key location was seen as a unique opportunity to promote the Starbucks operation in Ireland.

To this, some Dubliners say, “Ugh!”

In coffee, drones are most often associated with half-baked delivery schemes. Yet one impressive Lewis University student and entrepreneur on the outskirts of Chicago has a better idea: using drones in precision agriculture to provide actionable data to farmers. As Drone360 reports, Lyela Mutisya is the daughter of a Kenyan coffee farmer, a connection that has inspired her to help the plight of coffee farmers by using some practical applications she’s developed during her studies and extracurricular endeavors:

In August 2015, Mutisya started her own coffee importing company called Kahawa Yetu, Swahili for “our coffee.” Through Kahawa Yetu, Mutisya helps her father import and sell his coffee in the U.S. — and gains a working knowledge of the complex coffee importing, cupping, and roasting world.

When Mutisya speaks of coffee now, she’s well versed in the challenges that coffee farmers face: destructive pests, expensive fertilizers, and various diseases. These are all detriments to the production of high-quality coffee — and challenges that drones can help with. She explains that Kenya’s coffee production was highest in the late 1980s, but the country’s coffee production has sharply declined since.

“Ethiopia is the leading African nation in soil loss and degradation and, according to FAO country assessments, the resulting vulnerability to drought, crop failure and famine,” explains the lead to a blog post last week from the farmer-forward cooperative importer Coop Coffees. (Here’s a little reminder about the importance of soil health to coffee). With this in mind, the group has collaborated with Sidama Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union, while partnering with Soil & More Ethiopia, to launch a potentially replicable soil regeneration effort. Here’s more from Coop Coffees on the efforts in Sidama:

With the support and partnership of Soil & More Ethiopia and SCFCU, we were able to facilitate and sponsor a week-long visit and workshop on soils, composting and productivity with some 30 SCFCU producer representatives from Fero, Telamo, Taramesa and Shilicho cooperatives. We were joined by Elise St. Pierre, a Montreal-based biologist specializing in soils and biochar, Kevin Walters, co-owner of Alternative Grounds and BoD member of CoopCoffees, and European coffee colleagues from Roasters United.

The primary objectives of this first-of-its-kind workshop in the Sidama Region, included: hands-on learning, a shared understanding about the role of beneficial micro-organisms essential to healthy soil, the on-site construction of a 5 x 15 meter compost windrow, and the application of “regenerative” organic farming practices in farmers’ fields.

Honduras suffered some of the worst losses during the coffee leaf rust epidemic that spread throughout Latin America beginning in 2011, making it ripe for academic analysis regarding subsequent adaptation efforts. Those efforts took a major hit earlier this year when World Coffee Research confirmed that the previously rust-resistant variety Lempira — which has been planted in high numbers following the initial outbreak — had lost its resistance.

A newly released study awaiting official publication in the Journal Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems digs deep into resiliency efforts throughout Honduras, while exploring the attitudes of farmers who have been forced to adapt after devastating crop losses. A major takeaway from the research is that greater cultivar diversity is needed — that replacing one variety with another one leaves farmers susceptible should resilience fade for the new variety. The full study is here, but following is one of the more interesting passages (keep in mind that this research was conducted before Lempira’s susceptibility was proven):

Farmers were well aware of the vulnerability of commonly grown C. arabica varieties Caturra and Catuaí to CLR, which was expressed both through interview responses and the adoption of hybrid varieties—all cultivars planted between 2012 and 2015 were CLR-resistant hybrid varieties. However, farmer perceptions of cultivar diversity varied. Some denounced all non-hybrid C. arabica production, which to them represented the continued presence of CLR, and therefore continual degradation of CLR-resistance in hybrid varieties. Other growers expressed concern that coffee cultivation had simply shifted from Caturra and Catuaí towards the two most common CLR-resistant varieties, Lempira and Ihcafe-90. As one organic grower noted, “What they did was just leave Caturra, leave the coffee that gets this disease, and change to another” (translation by author). In other words, farmers worried that the continued reliance on a small number of varieties would maintain the same narrow range of diversity that brought a CLR crisis of such severity.

Both of these attitudes—concern for degradation of CLR resistance, and concern for the vulnerability to pest and disease outbreaks—point to the lack of resilience through cultivar diversity. Lempira and the rest of the Catimor progeny will likely lose CLR-resistance over time, just as the multi-line variety hybrid variety Colombia, released in 1981, which lost resistance to CLR in the early 2000’s (Alvarado and Moreno 2005).

Nick Brown

Nick Brown is the editor of Daily Coffee News by Roast Magazine.

Comment