When coffee beer enthusiasts mention some of their favorite brews, names like Founders’ Breakfast Stout, AleSmith’s Speedway Stout, and Lagunitas’ Cappuccino Stout are often repeated. It’s as if when considering this category, the mind jumps to these kinds of dark, thick, luscious, creamy brews that pour more like motor oils than pale ales. Several creative brewers say it’s high time to expand the mind.

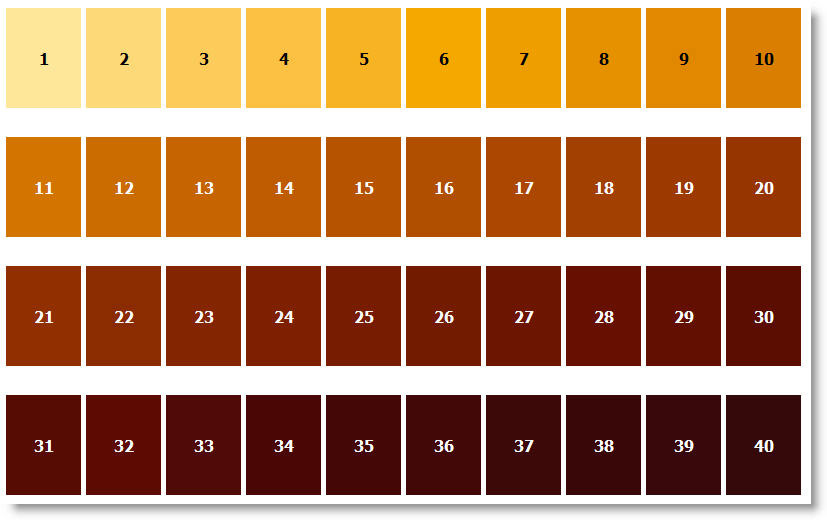

Coffee beers can actually span a huge spectrum of colors, ranging from dark walnut to light birch. Beer’s hue is measured on a scale called the Standard Reference Method (SRM), which is defined as “beer color intensity on a sample free of turbidity and having the spectral characteristics of an average beer is 10 times the absorbance of the beer measured in a 1/2-inch cell with monochromatic light at 430 nanometer.” In layman’s terms, it’s the color of the beer and how much light can pass through it.

Most of the time, coffee beers fall on the higher end, which goes from 1 (very light) to 40+ (the darkest dark). In competitions, however, coffee beers do not have an assigned SRM range, which actually allows them quite a bit of flexibility when it comes to brewing. This has led to some surprisingly light-colored but full-bodied beers.

Part of the fun of paler coffee beers is the mismatch of visual perception to flavor. When you see a light, bubbly, golden-colored pint, it’s easy to assume the flavor will be somewhat crisp and delicate. Most people’s mental image of coffee doesn’t match up to that.

“Folks are alway surprised by it,” said Aztec Brewing’s John Webster when discussing the brewery’s Coffee Blonde. “So many stouts and porters have natural coffee tones that it is not too surprising to get one with coffee added. But the Blonde… no one ever expects a light beer to have so much coffee flavor.”

Bay City Brewing Company’s head brewer Chris West agreed, saying, “Most of the time we get a positive response [to our Coffee Pale Ale], although people expecting a coffee stout are normally a little shocked.”

Many other craft brewers have enjoyed playing with this surprising combination for years, coming up with acclaimed “blonde coffee” beers like Three Daughter’s A Wake Coffee Blonde Ale and Old Forge Brewing Co.’s Coffee Kolsch. Brewers have even mixed coffee with hop-forward brews like India Pale Ales (IPAs) like Rogue Brewing’s Cold Brew IPA, or really flipped the tables with uber-malty beers like Sun King’s Java Mac or Cascade Lakes’ Blonde Coffee Stout.

Coffee roasts don’t follow such detailed consumer-facing color guidelines — coffee packages tend to promote simpler associations such as light, medium or dark — though roasters themselves pay strict attention to color using advanced analysis tools that pick up on the slightest change. Yet for beer, the color depends more on the malt used than the particular roast of any coffee added.

Chris Schooley, co-founder of Troubadour Maltings, an artisanal custom malt company in Colorado and a longtime professional roaster, is in a unique position to shed light on the differences between color in coffee and malt.

“The specialty malts used are, of course, the major contributor to the color of a beer, but the main difference between dark and light colored coffee beers is the function of the coffee itself in the recipe,” Schooley said. “In darker coffee beers, the coffee is mainly used as a bittering addition to add those roasty and cocoa notes. In lighter beers, the coffee is used more for aromatic properties to highlight more of the fruited notes of a particular coffee.”

Striking the right balance between coffee aromatics and flavor while maintaining a light appearance can require quite a bit of trial-and-error experimentation. When brewing his Coffee Blonde, Webster describes how the brewing technique evolved.

“We started out by what was in effect ‘dry hopping’ with coffee beans instead of hops. We used whole coffee beans, which imparted flavor but little color.” He goes on to describe the method as good, but inconsistent — something not generally acceptable for larger commercial batches. He then tried sourcing organic extracts, which yielded better consistency but at a high financial cost. Ultimately, Aztec Brewing settled on adding a blend of in-house cold brewed coffee on nitro to the beer.

“It adds a slight hint of color,” said Webster, “but remains a golden blonde and the flavor balance is excellent and consistent.”

The terroir of coffee beans used in coffee beers plays a huge part in how successful lighter coffee beers end up. Schooley explains how “clean and bright” washed coffees with tropical fruit flavors, as might be found from Kenya, lend themselves well to lighter beer styles. He goes on to describe how the dried fruit notes from natural-process coffees tend to work well for both light and dark coffee beers by “getting a lot of those deeper cocoa coffee qualities and the winey fruit notes… the aromatics are eye-popping.”

The difference in brewing process between dark coffee beers and light coffee beers is minimal, but the details that cause the stark visual divergence are key. And while blonde coffee beers haven’t yet caught on in mainstream beer culture, the symbiotic relationship between two of America’s favorite “vices” positions them as a real challenger for the next big brunch beverage.

Beth Demmon

Beth Demmon is a San Diego-based food and drink writer and aspiring BJCP judge. Check out her work at bethdemmon.com or on Instagram at @thedelightedbite.

Comment