The rise of specialty coffee over the decades has seen it evolve from guzzled commodity stuff into something more refined, traceable and, importantly, enjoyable beyond the mere function of caffeine delivery. Through this time, it’s taken innumerable cues from the world of wine.

Oftentimes for better and sometimes for worse, coffee and wine beg for comparisons: Both undergo transformative journeys from farm to cup before reaching their destination, where consumption of either beverage often remains a personal and emotional affair.

Arguably, no one to this point has compiled a more exhaustive comparison of the occasionally intersecting and often parallel worlds of coffee and wine as has Morten Scholer in his new book “Coffee and Wine: Two Worlds Compared.”

Published in October from UK’s Troubadour Publishing, the text spans more than 300 pages, providing a comprehensive and decidedly non-emotional overview of each beverage, from farm to cup — or, more accurately, from agricultural material to the finished, consumable product.

From Denmark, Scholer is an economist who served for 14 years as the senior director of United Nations’ coffee projects. While Scholer’s data collection on the worlds of coffee and wine have been ongoing since 2004, it was only upon his retirement from the U.N. in 2013 that Scholer was able to devote his full attention to the “Coffee and Wine” project.

We caught up with Scholer via e-mail to discuss the book, while naturally inviting him to share some of his own comparisons of these two enchanting beverages and the complex sectors that make their production possible.

Can you give us more on your professional background both in the worlds of coffee and wine?

Yes. I am an engineer and an economist by training from universities in my home country of Denmark. I’ve had jobs in private companies and public organizations, which all had one thing in common: They were related to developing countries, primarily in Africa and Asia. That experience gave me the opportunity in 1999 to join the International Trade Centre, a U.N.-agency in Geneva, Switzerland, where I coordinated coffee projects in many countries for 14 years. I also coordinated the publication of ITC’s extensive Coffee Exporter’s Guide, which is accessible online for free.

Wine has never been part of my profession. In my late 20s, I spent two holidays in the grape harvest in France and that stimulated my interest for wine. Now I pick grapes in the harvest in Switzerland where I live, and with friends who produce wine in Denmark.

What was the impetus for writing this book? What about these sectors or industries in your mind makes them so closely related?

While working with coffee projects I noticed that people often made references to the wine sector with admiration and sometimes envy. The references were to the sensory descriptions, the branding, the use of the term terroir and the high prices.

Out of curiosity I began to compare the two products and the two sectors at all stages from tree and vine to cup and glass.

The book describes one hundred differences between coffee and wine. When invited to present my findings at conferences, I have usually described just four fundamental differences.

First of all, for coffee, the value chain — the collaborative trail — is long and has many parties involved at different locations. For wine, it is short since the growing, the processing, the packaging and the sale usually happens at the same place.

Secondly, for wine, there are many options for quality enhancement — at least two dozen. There are few only for coffee — primarily related to pulping and drying.

Thirdly, some coffee companies are huge, holding fifteen percent or more of the world market. In the wine sector, the largest companies account for less than 3 percent of the world’s production.

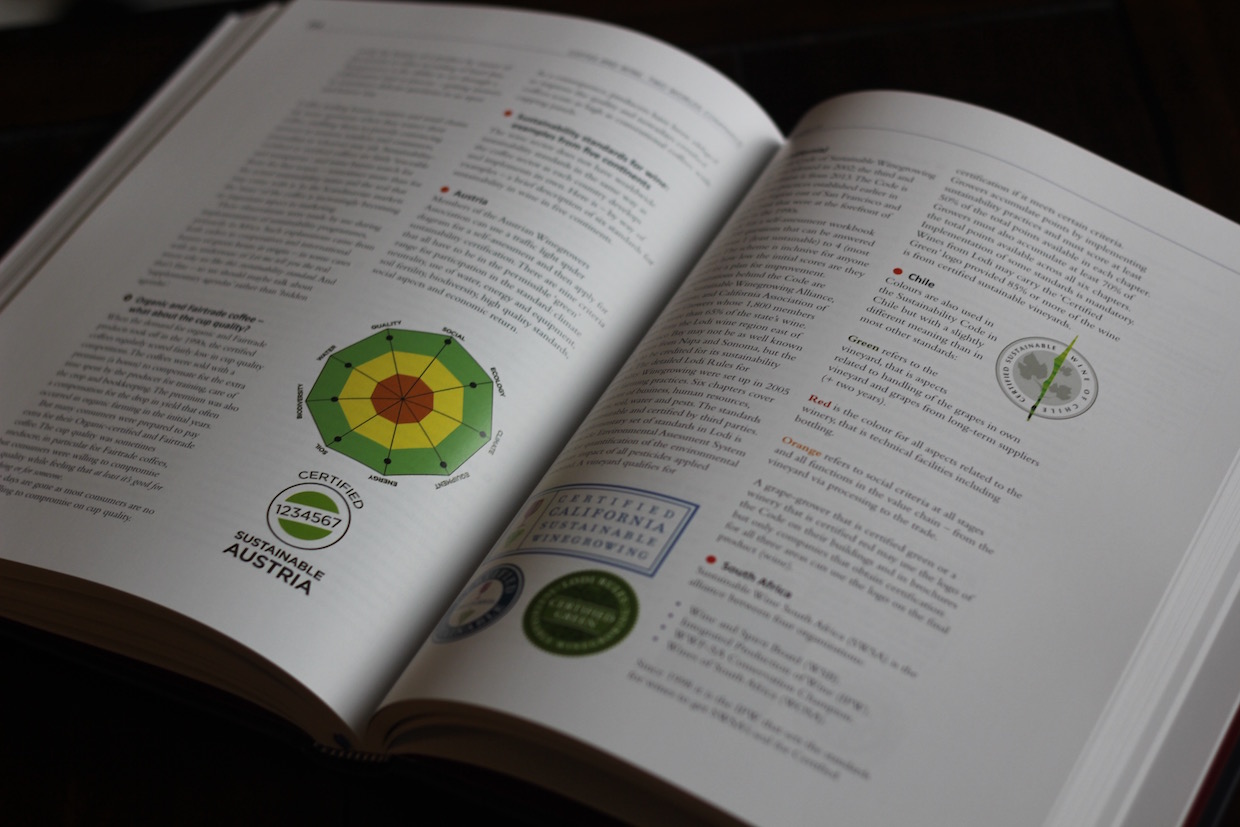

And, finally, the sustainability standards are in several ways more complex for coffee than for wine, which is not to say that the standards for wine are simple and easy.

In terms of marketing and approaches towards quality and professional development, it seems coffee has borrowed quite a bit from the wine world. What, if anything, has wine borrowed from the coffee world?

There is an area where the coffee world in a way is further developed than the wine world, and that is on harmonization of sustainability standards, despite the more complex conditions for coffee than for wine.

What do I mean by that? The coffee community has a handful of sustainability standards — primarily Organic, Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance (which now also includes UTZ) and the Global Coffee Platform with its 4C Code. These standards are the same worldwide, whereas the wine sector works with national or regional sustainability standards. In other words, each wine country can set the bar as high as it likes for all three dimensions: environment, social and economic.

What is impressive and admirable in coffee is that these global standards involve millions of people in long value chains with partners in several countries. And many of the partners, smallholders in particular, have very little education. It is a huge task to agree internationally on the conditions in these standards, to arrange training for millions of producers, to comply with the conditions and eventually to monitor and certify the long trails. I imagine that the wine world could learn something from this global cooperation and harmonization.

As mentioned, the coffee community admires the wine sector but the coffee community has good reasons to be proud of itself. Let me give you a couple of examples:

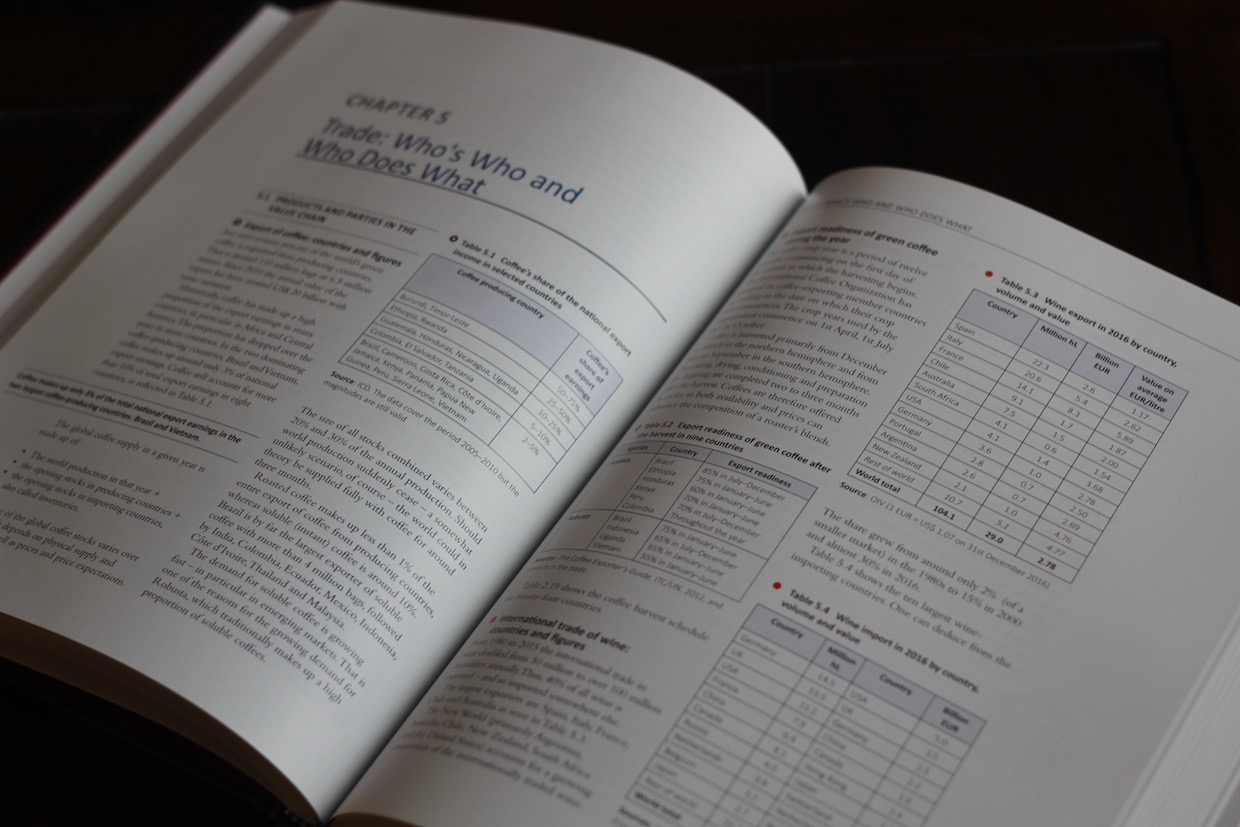

The world consumes more than two billion cups of coffee every day but only half a billion glasses of wine.

At farm level, the yield is high for coffee with an annual average production of beans for around 100,000 cups of coffee per hectare. On average you’ll get only 40,000 glasses of wine from one hectare with grapes.

The global consumption of coffee is growing at around 2 percent annually, whereas it has been stable for a decade for wine; and the wine consumption in Europe has even dropped significantly in the last 40 to 50 years.

The emission of CO2 from growing, processing, transporting, brewing and consuming coffee is around 60 mg per cup of coffee without milk and sugar, whereas it is around 240 mg per glass of wine.

As the specialty coffee sector has developed, we’re now seeing Cup of Excellence coffees or, say, highly prized Geshas selling for extremely high prices at auction. Could you have envisioned this? And is it necessarily a good thing for the coffee industry and/or the coffee trade?

I had the privilege of being associated with the first Cup of Excellence competition in Brazil in 1999… The idea was to show a link between producers’ efforts, cup quality and price, and to discover otherwise unknown small producers, often in remote areas. And it worked.

Nowadays, a high portion of the COE’s most expensive coffees go to Japan and South Korea — two countries that are known for not compromising on quality. However, giving and receiving famous brand products is connected with a lot of prestige in these countries, so it’s the name as much as the actual quality that sells. Overall, I think that’s fine for the coffee industry, not least because of the promotional effect the Cup of Excellence has for coffee in general in these countries where the consumption per capita is half of what it is in Europe and North America.

What do you see as the most pressing challenges currently facing the wine industry? And the coffee industry?

Both sectors are exposed to climate change, and things change fast. The spontaneous recommendation is the same for the two sectors: First of all, change to other varieties, and secondly, move to a higher altitude or further away from Equator; but for most producers, that’s not a real option.

It is great to see how much advice there is on options for a shift of varieties. In the case of coffee, I am impressed by the guidelines from World Coffee Research that has published a Coffee Varieties Catalogue, a guide for coffee farmers who plan to shift to an alternative Arabica variety.

There are somewhat similar guidelines for growers of wine grapes, but in their choice some of them are up against long-time established appellation criteria, which permit only a few grape varieties. That’s an obstacle in France and other countries in Europe, more [so] than in the New World of wine, which is more geared to trial-and-error experiments.

Nick Brown

Nick Brown is the editor of Daily Coffee News by Roast Magazine.

Comment