Despite what may be the best intentions of both parties, a natural gap in communication often exists between U.S. coffee companies and nonprofits, NGOs and others working to improve conditions in the coffeelands.

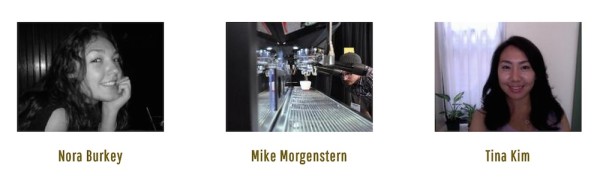

The Chain Collaborative, a new venture led by three coffee-minded people currently based in New York, hopes to eliminate that gap by serving as an intermediary between farmers, cooperatives, nonprofits, other origin-focused organizations and people working stateside in the specialty coffee industry.

(related: Revising the Record of Coffee’s History to Include Farmworkers)

The group incorporated last month and is hoping to achieve nonprofit status by summer 2015. In the meantime, The Chain Collaborative is hitting the ground running with numerous partnership-driven events, including benefit concerts and the group’s first “residency” program, involving Irving Farm Coffee Roasters and their wholesale partner Daily Press Coffee. Beginning today for the next three months, $1 for every 12-ounce bag of coffee sold at Daily Press’s two New York locations will benefit Pueblo a Pueblo, which works to improve conditions among coffee farming families in the Santiago Atitlan region of Guatemala.

(related: How Beekeeping is Helping Farmers Cope with La Roya in the Guatemalan Coffeelands

)

Chain Collaborative founder Nora Burkey, who has contributed multiple stories related to the coffee trade for Daily Coffee News, says she hopes the residency will be the first of many, as the group expands its network of relationships connecting roasters and retailers to the coffeelands. We asked Burkey more about the Chain, how it came to be and relationship issues in coffee:

What was the thinking behind the residency concept?

We want our residencies to be three months long, so as not to put too much strain on one company. Not running a company myself, I listen to what people say, which is that specialty coffee is often not all that lucrative. I think that’s mostly true, but I also get the sense people might have at least a couple hundred, so three months seem to us like a good length of time. It allows companies to become involved, get their customers more involved with what specialty coffee is capable of, be creative with their own ideas, and use their space for community events — what a coffee shop is all about — while at the same time not exhausting their resources or tiring people out with the same initiative month after month, year after year.

How are you connecting with your partners working at origin?

I met Planting Hope before starting the nonprofit. The executive director and I had a Vermont connection, not anything coffee-related, but I wanted to hear more about them and they wanted to learn more about my work in Nicaragua. After sharing my work and then becoming so enthusiastic about their connection to children of migrant coffee laborers in Matagalpa, I said I’d love to come back to Nicaragua and help their coffee camps expand into more communities. The organization was at a bit of a crossroads regarding their own next steps, and the staff in Nicaragua were thrilled about that idea. So we all started talking more about possibilities, and we’ve been collaborating ever since.

[Chain Collaborative founding board member Tina Kim] used to work for Pueblo a Pueblo, so that’s how we learned about them. She had 2 years with them, so a huge personal connection. So we’ve been lucky in how easily we’ve been able to “vet” the two non-profits we’re teaming up with.

I also spent time with the cooperative in Peru we’re supporting, down to trusting them with my life on some most epic motorbike adventures, so I also got lucky in finding such great partners in Peru. In terms of supporting their women’s committee, I asked the coop what initiatives they would most likely want companies to support. They told me their women’s committee, so we agreed. We then set out to find companies who might be able to contribute.

Can you talk about the relationship gap?

I became so inspired to do this after meeting the struggling non-profit in Nicaragua, Planting Hope. They work in coffee-growing communities, but have trouble connecting to the coffee industry. Their skill is development work and education of children, not coffee. When I met them, they informed me they were worried they wouldn’t get funding for their coffee camps initiative for the coming year. They also were not well connected to cooperatives in Nicaragua. In one day I got them a meeting with CECOCAFEN, and they were amazed. They have written me into their grant for the next year to develop a monitoring and evaluation program for their coffee camps initiative for the coming year. They felt they needed a coffee professional in order to produce a lot of things their granters wanted them to produce, like a manual for other coffee growing communities.

Coffee companies ask for coffee-related proof that things are working for the coffee industry. Planting Hope can tell you how well kids are reading and what they are eating, but they don’t know how to talk about coffee or what is important to coffee people. They don’t know much about the supply chain and have focused their fundraising efforts on other things. The coffee industry is one they haven’t tapped into all that much, and they don’t feel confident talking to coffee people. We can be an intimidating bunch. But my sense is that they are really grateful to us for the support and connections in the coffee world that they 1) didn’t know existed and 2) couldn’t make even if they tried. I think there needs to be a resource out there for them that lets them keep spending all their time focusing on their area of expertise: education for kids in one tiny area of one small coffee-growing country. Let someone else be the expert in talking to the coffee world.

The same goes for Pueblo a Pueblo. They are a bit more connected to the coffee world but are also really small and therefore strapped for resources. By raising money for them, we offer free developmental support like free fundraising. Nonprofits love that.

Isn’t there a kind of redundancy in a nonprofit connecting other nonprofits to the industry?

All money we raise for these nonprofits goes to these nonprofits. We take none for ourselves. That might be more than most small nonprofits can even say for themselves. We also hope that our residencies, though short-term, will inspire companies to make personal connections with the nonprofits they choose to support. We hope it encourages consumers to make personal connections. I think that’s a valuable and free service smaller non-profits appreciate.

Also, we raise money for other initiatives that are not nonprofits. CAC Pangoa is not a nonprofit, for example, but they are a cooperative. We know that coffee companies can make their own connections with both coops and nonprofits and start their own projects. But companies do not always seek out nonprofits to support, they seek out farmers to support. Helping farmers is great, but couldn’t we encourage more folks to help farmers if there existed a nonprofit to channel funds through? That could make donations tax deductible for one thing, but the other thing is that a lot more can be done the larger our networks are.

The more you visit farms, the more you learn that many people are helping the same farm in the first place. We’re rarely as special as we think. If we came together more and acknowledged that other companies have their helping hands out, our impact could be larger because we’d be doing things together and not wasting resources, such as travel to origin.

I also think there does need to be a professional resource for coffee companies who want to do good work. I love that many coffee people are a passionate and genuinely concerned bunch. But they are not development professionals. I do believe we need to include development professionals when we work with farmers. Otherwise coffee companies run the risk of creating unsustainable projects that fail. DIY is great. DIY plus working with someone who knows way more about public health than you do creates a better public health project.

What about this work appeals to you personally?

One day I asked myself what job I wanted in my life, and the answer was that I wanted to ask people what they wanted, and find a way to give it to them. I guess I didn’t feel that job existed, so I decided to create it myself. I also love coffee. My bigger passion, though, is development. My experiences in Cambodia taught me that development is not about thinking about how many people you’re affecting; t’s about trying to help as many as you can, even if that’s just one person. I see so many issues at origin that I can’t even begin to name them, but I can’t be daunted by how much I won’t do, or I’ll never do anything.

I also sometimes think about the nuances and condescension involved with being at origin. That’s why I don’t go looking for farmers to work with and work with those who come to me. That’s how I square that. I am also very angered by how we trade. I read extensively about trade, and it’s my study of sustainable development that makes me want to disrupt the way things are.

Speaking of some of the unlimited issues at origin, what are some that you feel deserve most immediate attention from the industry?

Many people are focusing on issues like water or food security. Climate change is obviously a real issue and the climate and environment are hugely important topics. But I am much more personally interested in trade. There are so few people disrupting trade, and when you don’t do that, you don’t advocate for farmers. I don’t see enough farmer advocacy and I don’t see enough people helping shift some power from the North to the South. If we did that, maybe climate change and food security initiatives wouldn’t be just the at the whims of donors and organizations, their support could be demanded in transactions. As an industry we allow ourselves to do so little and call it normal, but I don’t think normal ever made change.

Nick Brown

Nick Brown is the editor of Daily Coffee News by Roast Magazine.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Nick,

This is an interesting development in Coffee organizing.

As you must know , Thanksgiving coffee has been building its own bridges to coops for a long time and has in fact, worked with cECOCAFEN for 20 years . The Cupping Lab at SOLCAFE, their dry mill was built as part of a TCC/USAID project in 2000.

These three people have discovered a need that I have been working on for 28 years , but not as expansively, having my own business with its needs. But over the years my strategies to become an exclusive buyer of a coops coffee has changed to include other roasters once I found and made the connection with the farmers and helped them bring their coffee up to a specialty standard if it was necessary. Now I seek other roasters to share the coffee with.

Right now I am looking for 10 roasters to commit to 10 sacks per year for the only Laos coffee in the USA . It is a coffee that benifits 10 villages of the Jhai cooperative. Each ten sacks will generate enough to provide a new well for clean drinking water in the village. I was hoping to share this story with the roasters, provide the media so we could all tell the same story and become a collaborative that supports the Lao coffee farmers cooperative . The coffee is imported by Nicholas Hoskyns, a Nicaraguan Brit living in Nicaragua and who has worked with me as an ethical coffee importer for 15 years. He has deep roots in Nicaragua and is well connected to all the Cooperatives in Nicaragua and in fact, worked with the Government Ministry that handled the Venezuela/ Nicaragua trading during Chavez’s tenure.

We have the coffee in Oakland and the sacks are separated by village so each roaster can select a village to support and develop a relationship with. I will be (thanksgiving coffee ) will be just one of the ten roasters who join the collectiive and we all can work together as friends of Laos , refer consumers to the same web site for information, and build something together.

Paul katzeff

CEO Thanksgiving coffee Company