By Michael Sheridan of CRS Coffeelands Blog

Back in September, I published this interview with my colleague Ivania, who was born as a landless worker on Finca Malacara, one of El Salvador’s most storied coffee estates.

I was moved by Ivania’s story. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one.

José Guillermo “Epe” Álvarez Prunera, one of the owners of Malacara, was so compelled by the interview that he invited us to his farm. It may have been one those polite invitations Epe expected us to graciously decline, but we took him up on it. I am glad we did.

Last week, Epe and his sister, María de los Ángeles Murray Álvarez, opened the gates of Malacara to Ivania and her family. And Ivania and her family opened the doors of her home to Epe and María de los Ángeles. Both parties were kind enough to invite me and a few colleagues along for what was amounted to an extraordinary reunion of the extended Finca Malacara family.

I have been working in coffee for more than a decade and have been to more farms than I can count. But I have never been part of anything quite like last week’s incredible “Malacara family reunion.”

I am still working to make sense of it, to be honest.

Almost 70 years ago, Epe and María’s father Samuel Álvarez received a visit at his Finca Malacara from Ivania’s grandmother María Isabel Repreza, who arrived with five children in tow. He made room for her and her family, converting a chicken coop to temporary lodging until more suitable arrangements could be made. When he did, he tied the two families together.

A generation later, Ivania and her family were living in modest workers’ quarters in a hollow and Epe and Maria de los Ángeles in a big house on the hill above. As the crow flies, the two houses are not more than a few hundred meters from one another. But the families occupied different universes, and they never met until last week. And even then, their meeting seemed to be the result of exceptional serendipity. If I hadn’t I published an interview with Ivania, or if Epe hadn’t read it, they may never have met.

But they did meet, and when they did, the conversation focused less on what kept them apart for so long than what bound them together.

People

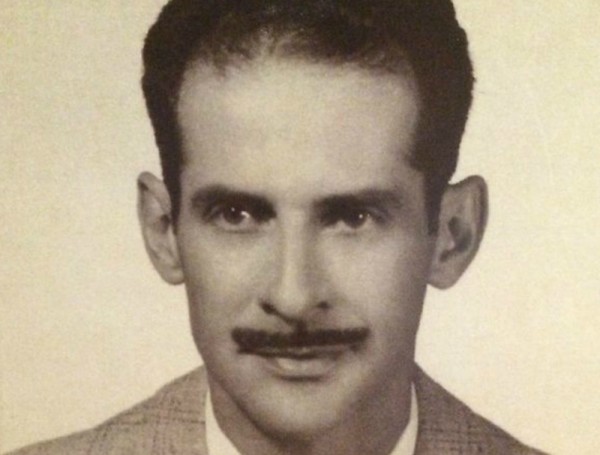

From the moment we picked up Ivania on the way to the farm to the time we said our goodbyes late in the evening, the conversation revolved largely around the great characters of Finca Malacara’s past — Don Raúl García, Chumpecuto, Maestro Andino — each one with a story. Nobody was more discussed — and clearly no one quite as beloved — as Don Samuel. He was Epe and María’s biological father and a kind of adopted grandfather to Ivania and her siblings, who never had a father or grandfather figure in their lives. Indeed, he seemed larger-than-life.

By the time his life was cut short at the age of 43, he had been a race-car driver, radio broadcaster, mayor, father, husband and charismatic patrón of Finca Malacara. My 43d birthday is right around the corner, and if I live twice as long as Don Samuel I will be lucky to achieve half of what he did. But what he did seemed less important to those who remembered him last week than how he did it. His humility, delight in the work of the farm, and kindness were threads that wove together the many reflections on his life offered last week. The memories of the Alvarez and Repreza clans are filled with many of the same characters from the sprawling cast in the drama that has unfolded over the past 50 years on Finca Malacara, starting with the man at the top.

Place

Finca Malacara is a magical place. It sits on the north face of the Santa Ana volcano in the Cordillera Ilamatepec, among the most celebrated coffee origins in the Americas, and has commanding views of Santa Ana and the valley that stretches out below from east to west. The histories of the Alvarez and Repreza clans aren’t just bound up inextricably with one other’s, but also with this landscape. They know it differently, of course, but both hold the memories of the place close.

Ivania’s oldest brother said that when civil war broke out in El Salvador he couldn’t understand what people had to fight about, since all he knew of El Salvador was Finca Malacara — a place that seemed to him like “paradise.” (As an aside, the fact that a revolution calling for land reform and radical redistribution did not resonate with a landless worker on a large coffee estate is extraordinary testimony to the quality of relations between labor and capital on Finca Malacara, and perhaps to the leadership and vision of Don Samuel.)

Commitment to Progress

Ivania’s family seems to share three firm convictions: Don Samuel was “a great patrón,” Finca Malacara was “a paradise,” and their best chance at upward mobility required them to get off the farm. The fact that Ivania and her siblings have found professional success is a great testament to their mother, who insisted on their continued education and sacrificed to make it happen. Epe and María de los Ángeles, for their part, delighted in Ivania’s story, the success that she has found off the farm and the role the farm played in her life. They understand the challenges and limitations of farm work, and they are committed to expand the opportunities available to farmworking families in and around Finca Malacara, first through the way they run their business then through projects to address needs in the broader community.

Epe recalls that when Finca Malacara placed second in El Salvador’s 2003 Cup of Excellence, it didn’t invest the proceeds from the auction in boosting yields or improving cup quality. The first investment he made was fixing the leaky roofs of workers’ houses. An acquaintance suggested to Epe that was no way to run a business, but Epe sees Finca Malacara as much more than a business. It is an institution in Santa Ana that has forged a social contract with the community–one he wants to honor in the way he runs the farm. As the day ended, we had only just begun to explore the ideas María de los Ángeles and Epe have for community projects.

I hope those conversations can continue. There are lots of big questions there. About farmworkers. About the role of coffee estates in the communities where they are located. About the limitations of agricultural labor in a world that is increasingly urbanized and a knowledge-based economy that is increasingly oriented toward the service sector. I can’t think of a better starting place than a meeting between farmworkers and farm owners bound together by so much history and so much goodwill.

In the meantime, I want to thank Epe and María de los Ángeles for being such gracious hosts, Ivania for being so generous with the details of her life, and all three for including me in last week’s amazing Malacara reunion.

Michael Sheridan

Michael Sheridan is the Chief Executive Officer of the Coffee Quality Institute, a nonprofit organization with a mission to improve coffee quality and the lives of those who produce it. Sheridan has been leveraging market forces to make coffee work for smallholder farmers and farm workers since 2004. Most recently he directed progressive green coffee sourcing activities and direct-trade partnerships at Intelligentsia Coffee. Prior to that he worked to deliver initiatives in the coffee sector in Central and South America on behalf of Catholic Relief Services.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Amazing stories of an honorable man. I heard plenty of stories by my grandpa who was born and raised there and witnessed Don Samuel Alvarez kind heart and enthusiasm for social progress. The school and catholic temple of Buenos Aires is his legacy…