(Editor’s note: This is a preview of an article that appeared in the May/June issue of Roast magazine. Click here to read the full article.)

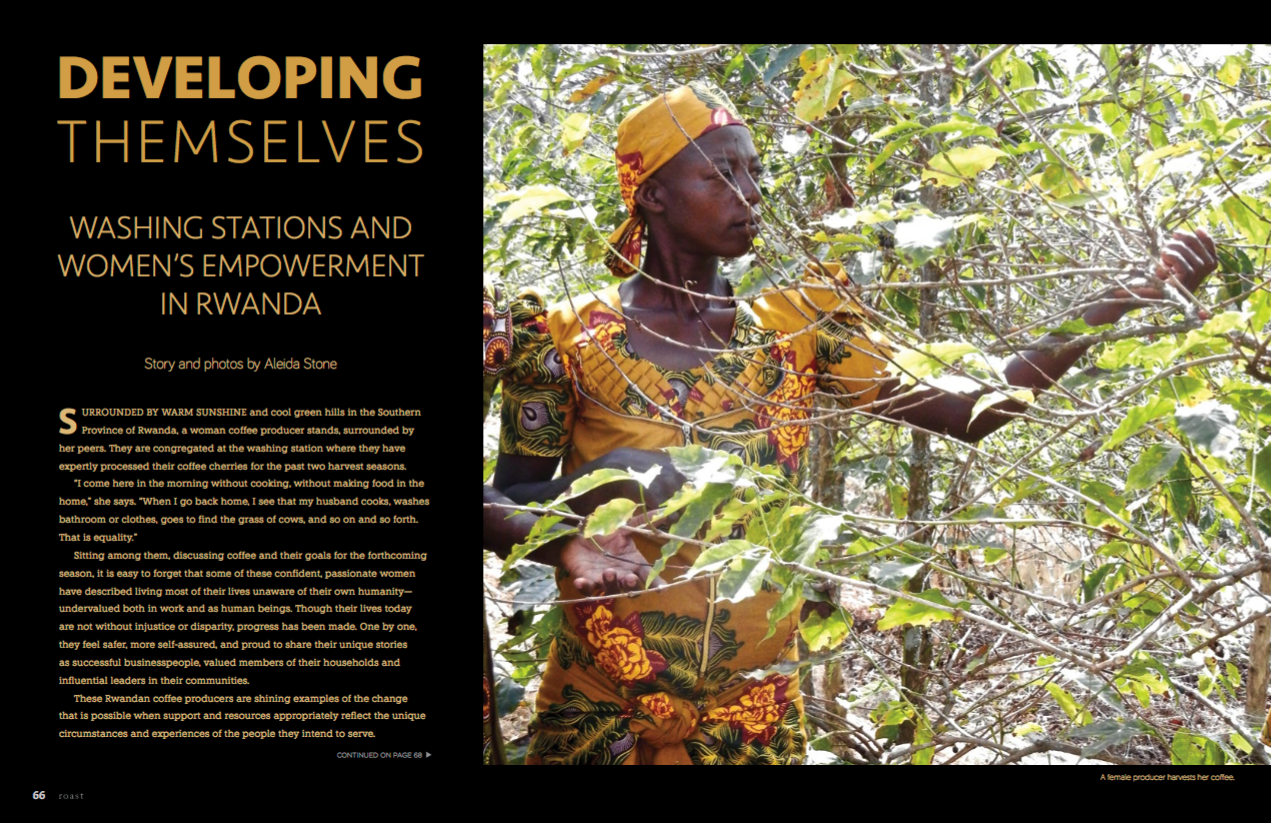

Surrounded by warm sunshine and cool green hills in the Southern Province of Rwanda, a woman coffee producer stands, surrounded by her peers. They are congregated at the washing station where they have expertly processed their coffee cherries for the past two harvest seasons.

“I come here in the morning without cooking, without making food in the home,” she says. “When I go back home, I see that my husband cooks, washes bathroom or clothes, goes to find the grass of cows, and so on and so forth. That is equality.”

Sitting among them, discussing coffee and their goals for the forthcoming season, it is easy to forget that some of these confident, passionate women have described living most of their lives unaware of their own humanity — undervalued both in work and as human beings. Though their lives today are not without injustice or disparity, progress has been made. One by one, they feel safer, more self-assured, and proud to share their unique stories as successful businesspeople, valued members of their households and influential leaders in their communities.

These Rwandan coffee producers are shining examples of the change that is possible when support and resources appropriately reflect the unique circumstances and experiences of the people they intend to serve.

Background

It seems obvious today that women and men experience the world differently, yet it was only decades ago that scholars of international development began specifically highlighting this reality. In 1970, for example, Danish economist Ester Boserup shone light on the fact that, during the 18th and 19th centuries, as European colonialism spread throughout Africa, rulers dismantled women’s status as instrumental actors within the agricultural sector, based on the presumption that men were inherently more effective farmers, despite the fact that farming was traditionally part of the women’s role. Men received resources and training, while women became less informed and less equipped to engage gainfully in the sector. As modern commercial agricultural systems progressed, women became increasingly marginalized. International development scholars Ruth Pearson, Ann Whitehead and Kate Young expanded on Boserup’s work in the mid-1980s, shifting focus away from simply acknowledging the presence of women toward documenting their unique experiences and roles within development.

It seems obvious today that women and men experience the world differently, yet it was only decades ago that scholars of international development began specifically highlighting this reality. In 1970, for example, Danish economist Ester Boserup shone light on the fact that, during the 18th and 19th centuries, as European colonialism spread throughout Africa, rulers dismantled women’s status as instrumental actors within the agricultural sector, based on the presumption that men were inherently more effective farmers, despite the fact that farming was traditionally part of the women’s role. Men received resources and training, while women became less informed and less equipped to engage gainfully in the sector. As modern commercial agricultural systems progressed, women became increasingly marginalized. International development scholars Ruth Pearson, Ann Whitehead and Kate Young expanded on Boserup’s work in the mid-1980s, shifting focus away from simply acknowledging the presence of women toward documenting their unique experiences and roles within development.

Undoubtedly, remnants of this time are still widely experienced around the world. However, thanks in large part to these scholars and many who followed, there is growing acceptance by international agencies and private-sector stakeholders — including green coffee buyers and roasters — that gender matters.

While working through my post-graduate research in development studies at York University in Toronto, it came as little surprise that existing studies and theories on both women and coffee recognized them individually and jointly as “means of development,” or tools that can be used to precipitate change. Coffee, a commodity produced almost exclusively in developing nations, can be a source of income for millions of small-scale producer households and is a popular focus for third-party certifications. Similarly, there is an ever-growing value being placed on women as essential contributors to household well-being, sources of economic and political stability, and stewards of the environment.

Having said that, the label “means of development” can, in fact, be a source of harmful oversight. It provides the industry with unrealistic expectations to value coffee and women as silver bullets, laying responsibility on them to solve broad and deeply rooted development challenges. This label fails to recognize that coffee as a commodity still encounters volatile global market prices and is, in many ways, unsustainable both environmentally and as a profession for a majority of producers. Women, as essential contributors to agricultural supply chains and households, still face lower wages than their male counterparts, sweeping sexual harassment and, in many cases, a doubling of their workload, as they are expected to continue their traditional household responsibilities in addition to laboring outside the home. The fact that unequal political and legal rights in many places do not support women’s specific needs clearly exacerbates these issues.

Having said that, the label “means of development” can, in fact, be a source of harmful oversight. It provides the industry with unrealistic expectations to value coffee and women as silver bullets, laying responsibility on them to solve broad and deeply rooted development challenges. This label fails to recognize that coffee as a commodity still encounters volatile global market prices and is, in many ways, unsustainable both environmentally and as a profession for a majority of producers. Women, as essential contributors to agricultural supply chains and households, still face lower wages than their male counterparts, sweeping sexual harassment and, in many cases, a doubling of their workload, as they are expected to continue their traditional household responsibilities in addition to laboring outside the home. The fact that unequal political and legal rights in many places do not support women’s specific needs clearly exacerbates these issues.

In an attempt to begin addressing this oversight and expand on traditional development strategies, I conducted my own research, exploring some of the ways female coffee producers can be supported not solely as caregivers and economic stimuli, but as empowered human beings.

[Click here to read the full article]

Aleida Stone

Aleida Stone is passionate about linking practical and theoretical understandings of the coffee supply chain. Previously a barista, roaster, trainer and wholesale account manager, Stone is a 2017 master’s of arts graduate in development studies from York University in Toronto and a freelance development consultant. At present, she is working on projects in Rwanda, Colombia and Guatemala, using research to support sustainable partnership development between coffee suppliers and buyers

Comment