Aymer Quinayas Ortiz uses shade to protect the native forests on his farm, Finca La Pelota, in San Agustín, Huila, Colombia. Photo by Mariana Reyes Serrano.

(Editor’s note: This article written by Jimmy Sherfey originally appeared in the September/October 2016 issue of Roast magazine.)

Consider the most exciting developments in coffee over the past few decades, and quality is most often the driving force. Specialty coffee professionals have looked beyond regions to explore differences by farm — and even by specific lots on a farm — by variety, by size, by processing method and more. Where and how microlots are grown and processed has an enormous impact on cup quality, and the variables seem to have no end.

This past decade, however, has brought something of a wakeup call. We’ve learned that for some of our most cherished regions, supply could well be finite. Regional drops in supply can be attributed to a number of problems: a global rise in temperatures, plant disease, and farmers abandoning coffee altogether.

Diversifying for a New World

To understand the most pressing problems — which appear to be exacerbated by rising temperatures, erratic rainfall patterns and other effects of climate change — the nonprofit World Coffee Research (WCR) commissioned the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT, by its French acronym) to classify global growing areas by climate condition, dividing regions into what is known in climate modeling as pixels. (Think of them as microlots, but for climates.) The pixels were grouped by common climate profiles, resulting in five agro-ecological zones: hot-wet, hot-dry, constant, cool-variable and cool-dry.

These zones are intended to help researchers focus on the different areas in which coffee currently grows, providing a more accurate forecast of where it might not grow in the future. Predicting how each zone would behave in response to 19 distinct climate-model projections shows that land suitable for coffee growing could drop by a staggering 50 percent over the next three decades.

“There is a key caveat with this kind of information,” CIAT senior researcher Mark Lundy noted during a presentation at the Specialty Coffee Association‘s Re:Co Symposium in April. “[Projections] are based on a range of climate models that often disagree. … They’re our best guess now, and these projections are what you can expect if we do absolutely nothing.”

Lundy added, “The work WCR is doing with varieties is a potential solution that could have a major impact, but it’s an arrow that is not yet in our quiver.”

Finca La Pelota, San Agustín, Huila. Photo by Mariana Reyes Serrano.

WCR multi-location variety trials currently underway across the globe will take some time to yield actionable information, and demonstrating the benefit of newly developed hybrids will add to the lead times. But as WCR Communications Director Hanna Neuschwander outlined in Roast’s March/April 2016 issue, if successful, these developments could help prevent potentially disastrous reductions in supply in the long term.

One particularly promising aspect of this hybrid development is a naturally occurring phenomenon of crossbreeding called heterosis, wherein the progeny of two genetically diverse parents perform better than either parent.

“With a hybrid, you’re picking parents based on the combination of desired outcomes,” Neuschwander explains. “If you know rust resistance is an outcome, one of the parents has to be rust resistant.”

While breeding for rust resistance has long been a goal for coffee breeders, WCR is working to expedite the development of new varieties, with quality as a key priority.

“The existing varieties had agronomic traits [breeders] wanted — high yield and resistance — but not necessarily quality,” says Neuschwander. “It’s our belief that it’s not a necessary trade-off. A big part of our breeding approach is bringing quality into the fore.”

She adds that existing high-performing, resistant varieties, which boast decent but not exceptional taste, began producing right around the time the market started focusing more heavily on cup quality.

“It takes 30 years to develop a variety through traditional methods,” Neuschwander says. “When rust showed up in Central America in the ’60s and ’70s, [breeders] started working on [new cultivars], and most of them didn’t get released until the late ’90s, but between 1970 and 1999, not many people cared about quality, except in a big, overarching way.”

“What many people used to keep in focus during the late 20th century was yield, and resistance to pests and diseases,” agrees Mario Fernandez, technical director at the Coffee Quality Institute, a nonprofit working to improve the livelihoods of coffee farmers by supporting increased quality. “That’s fair enough, because those were times when quality was not important, and when the specialty market was not as developed.”

Of course, the industry has changed dramatically since then.

“There is huge potential for new flavors, and huge potential for completely new surprises,” Fernandez continues. “The whole industry was surprised by geisha when it was rediscovered in Panama, but there is no reason we could not have another geisha in the next 10 years, when a new variety is developed and has a fantastic flavor in the cup.”

Matching Plants and Places

Perhaps the most pressing question for the future is, how will researchers place the most suitable varieties in the regions where they will be most resilient? WCR is running trials on molecular responses to various climatic conditions to identify the genes associated with different traits, which will assist breeders in deciding which parents to cross. (It should be noted that WCR’s work does not involve genetic modification, but rather traditional breeding techniques augmented by modern advances in computing, data science and genetic sequencing.)

“My job is to preserve the land, the nature, so the natural springs give life to my farm.” —Aymer Quinayas Ortiz, Huila, Colombia. Photo by Mariana Reyes Serrano.

“Molecular breeding is really common in other fruits and vegetables,” says Neuschwander. “The idea is that if you can identify up front some key genes and molecular markers that predict certain behaviors — one example is rust resistance — then you can take a sample of the leaf and screen it for presence or absence of that marker.”

That way, she explains, you can determine whether or not the plant will be resistant without waiting to find out in the field.

Alvaro Gaitán is director of Cenicafé, the research arm of the Colombian Coffee Growers Federation (FNC, by its Spanish acronym). If the FNC had not begun the breeding process for castillo in the 1980s, he says, Colombia might not have survived the subsequent rust outbreaks as well as it has, and could be in a situation similar to currently rust-racked countries in Central America.

“Many things in coffee have to be done way in advance, so you can avoid the problem,” says Gaitán. “For many years, coffee has been bred for rust resistance, and that’s still the world’s main problem. Rust is a fungus that changes all the time. It’s like a hacker. It’s always trying to find a way into coffee. So it’s a normal process in resistance that you have to overcome the pathogen continuously. We will always do plant breeding. You cannot stop at a particular variety and say, ‘This is it.’”

Once a new variety is developed, the challenge is to get significant quantities onto farms. This is where infrastructure is key. The FNC has set a sterling example when it comes to restoration efforts. With a massive network for understanding and interacting with Colombia’s 500,000 small farmers, the organization propagated disease-resistant castillo so rapidly and with such success that the 2013 and 2014 seasons produced pre-rust-outbreak levels, says Gaitán. Production grew by 83 percent from 2012 to 2015, according to FNC reports.

Colombia is “the only country I know that adopts a varietal en masse,” says Fernandez. “When the FNC develops and releases a new variety, it very quickly reaches thousands of farmers.”

In addition to infrastructure, Colombia enjoys some natural advantages over its Central American neighbors. CIAT’s agro-ecological zones characterize much of Colombia as constant, while the majority of the land from southern Mexico to northern Nicaragua falls into the hot-wet or hot-dry categories. A combination of rust and drought has plagued the region over the past five years. Much of the drought has been attributed to El Niño, which took a toll even on Colombia’s preferable conditions, halting four years of unabated growth and reducing the 2016 crop considerably.

Fruit trees provide shade for coffee shrubs and generate organic material for the soil. Photo by Mariana Reyes Serrano.

The FNC is working on a more nuanced understanding of its vast territory, taking into consideration terroir, biodiversity and elevation. Providing recommendations to smallholder farmers across 15 degrees of latitude, 80 different soil profiles and 86 unique microclimates is no easy task. For the time being, the organization offers design strategies and recommendations by location, based on the four prominent harvest periods.

“That’s basic, and for many things it works well,” says Gaitán, “but as you move into something more complex, like the ecotopes, where you look at things like watersheds, they are very particular and have their own characteristics. Are you going to give a specific recommendation for 80 separate regions? Four, OK, but 80, it’s really complex.”

To organize microclimates into a more manageable set, Cenicafé researcher Juan Carlos Garcia and his colleagues classified 12 regional “attitudes,” profiling behavior based on a number of metrics, including elevation, watershed, shade cover, weather and terroir, similar to the agro-ecological zones classified by CIAT. However, the federation is not ready to incorporate these classifications into its strategy just yet.

“It’s our first approach to understand the environment in a different way,” says Gaitán. “It’s important to think outside of the box a little versus what we did in the past, but we still need some time, a couple of years to land that idea into something that is practical.”

Mitigation Through Genetics and Agroforestry

Given the complexity of addressing climate change on an institutional level, what options exist for regions facing significant challenges related to global warming and pathogen spread? Adriana Villanueva, co-founder of the Colombian exporter InConexus, says chainwide awareness is key. Working in the coffee market for 15 years, InConexus began with business development programs in rural areas, with the goal of alleviating extreme poverty. While the firm trains smallholder farmers in quality production practices that have proven successful in the region, Villanueva says she and her colleagues have learned from farmers about sustainable agriculture and the proper tools for a given region.

“We began with the idea that we were going to develop these communities — ‘develop’ them, imagine the arrogance,” Villanueva quips. “We saw their incredible resourcefulness and realized they understood their local realities well, but what was missing was communicating global realities through the most efficient means.”

Respecting the farmers’ tools and knowledge is essential, she adds, as is understanding that solutions must be tailored for each microclimate and region.

“It’s the chemicals that have made us sick. The really good stuff we find in the earth, the organic [matter]. My job is to protect life.” — Julio Alberto Muñoz, Finca El Tabor, Huila, Colombia. Photo by Mariana Reyes Serrano.

“We certainly try not to preach, because in coffee there is no single solution,” he says. “On the contrary, if we preach anything at all, it’s that you need to understand your local context before you adapt any solution.”

While it will take time before the most valuable information related to molecular markers becomes available and its hybrid incarnations make it into production, there are promising, field-tested varieties now available through WCR’s variety catalog, first released in June 2016. Many of the hybrids recommended in the catalog were bred through international multi-stakeholder efforts, performing well in studies authored by Dr. Benoit Bertrand, a scientist with the French research institute CIRAD and the head breeder for WCR initiatives.

The main objective was to reveal the fitness of existing hybrids and varieties for a range of microclimates, but the studies often showed climate change mitigation measures and cup quality are not mutually exclusive. The most basic example is maintaining shade to reduce farm temperatures.

A 2012 CIRAD study conducted on Réunion Island, a small island east of Madagascar, measured volatile compounds associated with quality in coffees grown in different microclimates around the island. Results showed that “among the climatic factors, the mean air temperature greatly influenced the sensory profile,” suggesting that higher temperatures associated with climate change could have negative impacts on coffee quality.

“As the Earth warms up, adding shade can bring the temperature down on farms to cope with climate change,” says Fernandez. “This means in countries where shade is not used, such as Colombia, you still have a margin of flexibility by adding shade.”

Villanueva regards the Agustino Forest producer group in Huila, Colombia, as one of the most consistent producers of quality coffee that buck the full-sun trend, guaranteeing 25 shipping containers of coffee with the same cup profile scoring at least 86 points.

“In the past year, we had El Niño, and this affected the coffee, and the performances dropped terribly,” says Villanueva, referring to the averanado defect, a term commonly used in Colombia for coffee that has had its quality damaged by drought during the crucial seed-development phase. Farms also yield less as farmers are unable to fertilize coffee fields for lack of rain. “The only parts that took less of a hit were those that were under shade,” she adds.

Farmer Aymer Quinayas Ortiz on his coffee farm, Finca La Pelota, in Huila, Colombia. Photo by Mariana Reyes Serrano.

According to a 2012 CIAT policy brief on climate change, “Shade canopy benefits coffee production by maintaining soil moisture, protecting against erosion and landslides, and shading coffee plants from harsh daytime sun and heat,” reducing temperatures by approximately 4 degrees C.

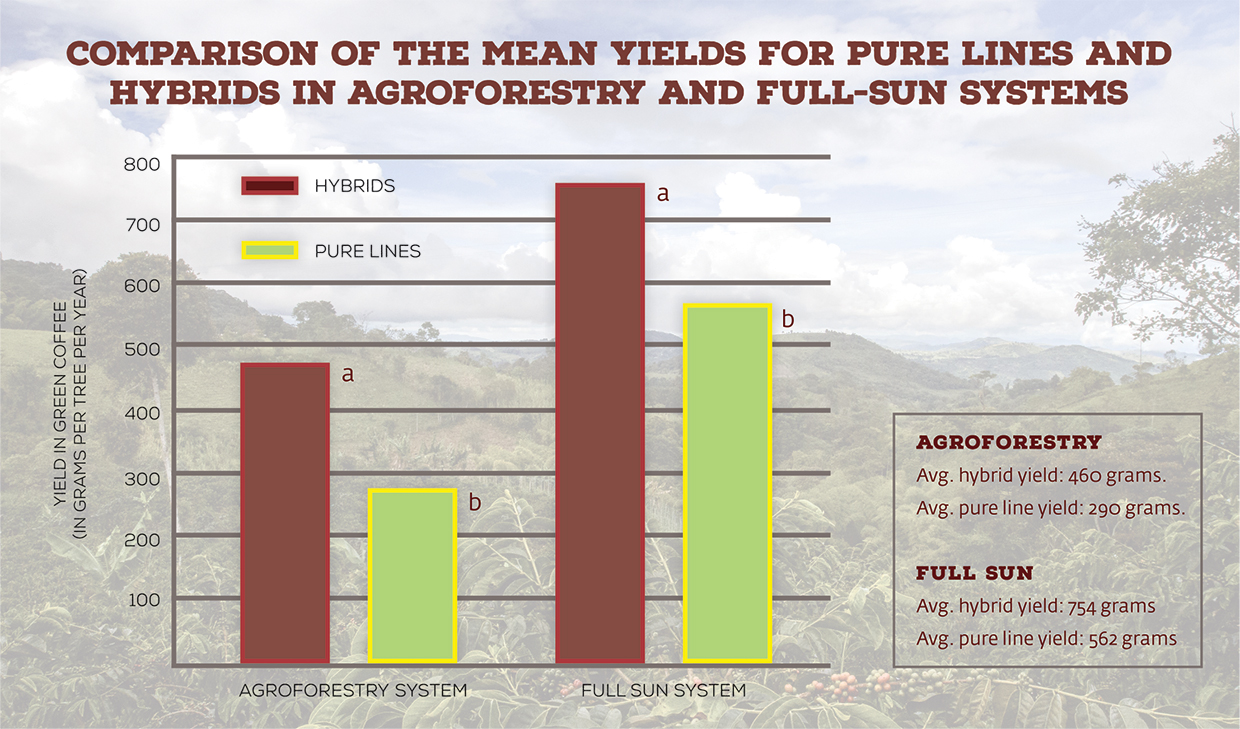

Although shade cover has been shown to reduce yields regardless of coffee genetics, the drop in productivity in hybrids under shade is not as drastic when compared to traditional cultivars in the same setting. A 2011 study by Bertrand demonstrated this, finding that hybrids possessing exceptional heterosis — like those being developed from the WCR core collection — performed better than their pure-line counterparts in shade-heavy agroforestry systems. (See chart below.)

In optimal conditions, yield from pure-line cultivars (such as bourbon, typica and caturra) was reduced by half when changed from full-sun to agroforestry systems — defined as anywhere from 20 to 50 percent shade cover on average, with variation in the number of trees at each site and the amount of foliage on trees across the year — whereas hybrids dropped by only 38 percent. The intense full-sun systems were located in Costa Rica and the agroforestry sites in El Salvador and Honduras.

Agroforestry plots also typically receive less fertilizer and pesticides. In addition to curbing applications that promote the growth of the plant, shade reduces the need for herbicides that inhibit the growth of weeds competing with the coffee tree for nutrition.

Dr. Robert Manson, a researcher at Mexico’s National Institute of Ecology, says agroforestry can improve quality for existing varieties, keeping on-farm temperatures down and prolonging the ripening process. Additionally, it can help countries meet preservation goals. As a country with ample shade cover, Mexico could benefit on both fronts.

“What makes Mexico different in terms of shade is the diversity and density, at 40 to 60 percent, with levels that Costa Rica, Panama, Brazil and a lot of other major coffee producers can’t hope to match with their low density [of shade],” Manson says.

Manson’s organization is partnering with CIRAD and WCR on a variety trial in Veracruz that includes 46 different altitudes spanning a range of microclimatic conditions and cropping systems on a number of farms.

“Some of the farms have more intensified and standardized management and others have more traditional management practices,” he says, “so we’re going to quickly see how these hybrids perform versus traditional varieties in these different contexts.”

Following drastic drops in production over the past three seasons, Mexico is scrambling for answers. It may boast more shade, but it also falls into a hot climate designation, as opposed to the temperate conditions of Colombia’s constant designation.

As rust proliferates across Mexico’s generally lower altitudes, many are clamoring for institutional support. The country lacks the infrastructure of the FNC, which financed the renovation of 50 percent of Colombia’s farms from 2008 to 2013, mainly with rust-resistant plants. That effort successfully restored production in only five years.

Given the production capacity of countries like Brazil and Colombia, a drop in Mexican supply does not necessarily mean a rise in Mexican prices. On the contrary, prices in Mexico have fallen significantly — from $1.80 per pound in 2015 to $1.25 in 2016, reports El Mundo del Cafe, a Mexican coffee trade magazine. This 30 percent drop has been attributed to the global surplus, coupled with a damaged market reputation.

Organic fertilizer made from coffee cherry pulp, cow manure and earthworm castings at Finca Buenos Aires in Huila, Colombia. Photo by Mariana Reyes Serrano.

In a parliamentary address, Jorge Alejandro Carvallo Delfin, a Mexican legislator from Veracruz, reported that some of his coffee-farming constituents have seen as much as a 70 percent decline in yields over the past three harvests. Without a change, this could pose further risk to Mexico’s imperiled coffee fields and their unique shade cover.

CIAT projections cite a 2006 study that predicted Veracruz production could fall out of economic viability by 2020, pointing to the damaging effect of higher temperatures and labor costs on yields. With labor accounting for 80 percent of production costs, a 30 percent drop in price — like the one reported this year — would spell disaster.

A 2012 CIAT brief goes a step further, reporting that market pressures could cause a drop in Mexico’s biodiversity.

“As unprofitable coffee farms abandon the crop, land will likely be converted for other uses, leading to fragmentation and loss of agroforest habitat,” the report states.

As an example, Manson points to sugarcane.

“When prices go down, sugarcane companies come in and talk to coffee growers, saying, ‘If you let us use your land, we’ll guarantee a rent paid to you, a certain percentage of profits. You don’t have to do anything. We’ll cut everything down, plant the sugarcane, even provide health insurance to you and your family,’” he says. “For a lot of coffee growers, that’s a really attractive deal.”

Helping Farmers Where They Are

While CIAT projects a decline in suitability for existing coffee lands, that does not mean that other areas, particularly at higher elevations, will not be viable for coffee production in the future. Currently, coffee is grown only in 2 percent of the total arable land suitable for the crop, and 60 percent of the area that will be suitable for coffee production by 2050 is currently covered by forest. In addition, the coffee industry will need to produce anywhere from 4 to 14 million additional pounds each year to meet growing consumer demand, according to a recent report by Conservation International.

As production declines in biologically diverse areas such as Mexico, there is pressure for growers to migrate up the mountain in search of the lower mean temperatures that play such a large role in quality and production. The resulting deforestation, however, would only exacerbate the problems of climate change. Deforestation rates are alarming in Chiapas, accounting for more than half the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to an earlier Conservation International report.

“Right above coffee farms are some of the last remnants of neotropical mountain cloud forest, a biodiverse but threatened type of forest in Mexico,” Manson says. “The risk is that coffee farmers could want to move up the mountain with climate change to be in the new sweet spot of production.”

While there are examples of coffee farms at higher elevations that have helped transform land from intensive agricultural operations with little shade to well-managed farms with extensive shade cover, the concern is that coffee farmers will be tempted to move into previously undeveloped, endangered forests.

“We have to help the farmers where they are,” Manson says.

The income produced from coffee alone does not appear to be keeping farmers in the game, but other income streams could help keep them afloat. Furthermore, the ecosystem services preserved by agroforestry models could provide incentives for avoiding full-sun production or resisting conversion to more intensive crops such as sugarcane. Shade trees can improve soil structure, for example, preventing erosion and potential landslides during extreme precipitation events. Leguminous shade trees fix nitrogen to the soil, reducing the need for fertilizers and producing organic matter that traps carbon in the soil.

The Colombian Coffee Growers Federation has had remarkable success with restoration efforts, including the development and dissemination of rust-resistant castillo. Photo by Mariana Reyes Serrano.

Because of this carbon-capture effect, agroforestry could reduce emissions that might occur in full-sun production. Capitalizing on carbon sequestration capability, however, has proven challenging, as the majority of carbon markets are still voluntary. To make coffee farming more attractive, Mexico’s National Institute of Ecology has data collection projects in place to remunerate traditional coffee farmers who preserve diverse shade cover on their farms.

“We introduced a legal reform to classify shade coffee as an agroforestry system that should provide double bene t to growers,” Manson says.

These reforms would make the farmers eligible for financing from the National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR) to help generate additional revenue. A typical ecosystem service payment is about 1,000 pesos per hectare per year, Manson explains. CONAFOR provides landowners with about 8,000 pesos per hectare per year to set up tree plantations, but coffee farmers currently are not eligible for these funds because they are considered strictly agricultural, which falls under the responsibility of a different government agency.

Manson adds that receiving payments from local municipalities benefiting from ecosystem improvements provided by coffee-farming communities, such as watershed management, is another possible strategy. As an example, he points to perennial Cup of Excellence contender Roberto Licona, whose farm La Herradura in Veracruz employs a highly efficient closed-system process for washing coffee that does not pollute the local water supply.

Farms also could receive financial assistance through certifications such as Rainforest Alliance and Smithsonian Bird Friendly. According to Bertrand’s cropping system study, agroforestry could benefit overall environmental preservation.

“Coffee agroforests, with shade trees interspersed amongst the coffee plants, are often the only habitat with remaining tree cover within these areas for migratory birds in the Mesoamerican biological corridor, as almost all forests have been removed at the elevations where coffee is grown,” the study reports.

Will There Be a Next Generation of Smallholder Coffee Farmers?

With new climate-smart technologies and improved varieties on the horizon, farmers could have a fighting chance at producing better quality coffee more profitably in the decades ahead. Nonetheless, even if the new class of hybrids is able to maintain adequate supplies amidst a changing climate, coffee has an existing labor crisis, most notably in Colombia, where production rebounded quickly following the rust outbreak but currently lacks an adequate number of harvesters to comb its fields.

Finca El Tabor, located at 1,800 meters above sea level in Huila, Colombia, uses shade trees to preserve the soil. Photo by Mariana Reyes Serrano.

While it’s easier for farmers in Brazil to handle large volumes — with less mountainous terrain, large harvesting machines can drive over rows of coffee, jostling ripe fruit loose — quality at this scale requires industrial sorting and processing equipment. It is a model that Colombia has reportedly experimented with despite its more mountainous terrain.

If the wider industry moves in this more technology-driven direction, the newer hybrids could be used to maintain supply in intensive systems currently operating in precarious agro-ecological zones, namely the Cerrado region of Minas Gerais, Brazil. However, a 2006 CIRAD report warned that there could be “negative ecological impacts” in full-sun systems such as Brazil and Colombia “because higher yields would have to be compensated by additional fertilizer applications.”

Already squeezed by the global market, smallholders — who represent coffee’s current bedrock of quality — likely will not be able to shoulder the cost of added inputs without passing these costs on to the buyers, particularly if institutional support in their country is low. This leads one to wonder: Will the less-productive but more ecologically sound methods of agroforestry become a viable model for quality coffee to rally around?

Whatever the answer, the trend of high global production and bottom-floor pricing does not appear to be working for the smallholder farmer.

“What about the price? Do we keep driving the market to the New York ‘C’ price?” posits Villanueva. “Nature is going to answer the question. The extreme weather in recent years is a affecting the quality of the coffee. … The solution is not grow more coffee, it’s grow better coffee.”

As long as high yields shackle the “C” price to the ground floor, poorly remunerated, quality coffee production will continue to be an unattractive proposition for the next generation of smallholder farmers, and the reality of sugarcane stealing the show from quality coffee at origin, as it too often does in the cafe, could become even more common.

Finding a more thorough definition of quality — the very thing that separates specialty coffee from commercial — will be crucial to the industry’s survival. In the years ahead, we will have to discuss, debate and ultimately answer some challenging questions. What are the different levels of quality? How do factors such as genetics, yield and efficiency affect the cost of producing quality coffee? Who are the stakeholders in specialty coffee, and are they willing to pay the costs at each level.

Jimmy Sherfey

Jimmy Sherfey is a freelance journalist and licensed Q-grader interested in specialty coffee production and the triple bottom line of sustainability. His blog, abeja.coffee, studies the ongoing struggle of good coffee and how strong, transparent relationships between producer and roaster can help. Find him at one of the many new, quality cafes of Orlando, Florida.

Comment