Laty Keopiensy prepares a Jing Jhai pourover at the opening of Kafelao, a new specialty cafe in Vientiane, Laos, in February 2020. Photo by Timothy D. May/Winrock International.

“…A lot of cranberry…orange blossom, very plummy…really great raspberry, jackfruit…strawberry cream yeah! …honey-orchard-oolong-melon-almond-sugar cookie…dark chocolate notes…nice sweet vanilla…lower tones of nuts, nuttiness…”

Coming in rapid succession, these were some of the descriptors read aloud in real time by Tim Heinze, a specialty coffee expert and trader for a multinational coffee company who ordinarily lives and works in Papua New Guinea.

Standing apron-on in the dining room of his in-laws’ house in Dallas, Heinze nodded in agreement with many of the overwhelmingly positive assessments, several noting fruitiness, scrolling down his computer screen, while he occasionally offered his own rapid-fire sensory impressions.

The focus of all this simultaneous tasting was a selection of roasted coffees coming from Laos, an origin that despite a long history of arabica and robusta cultivation does not always have connections to international buyers.

The event itself was the first ever virtual cupping organized by the nonprofit Coffee Quality Institute

in partnership with USDA’s Creating Linkages for Expanded Agriculture Networks project, implemented by Winrock International. Most of the more than 50 participants in the cupping were tasting coffees from Laos for the first time.

A coffee farmer seeking ripe cherries at a coffee farm on the Bolaven Plateau. Photo by Phiengphaneth Chanthalansy/Winrock International.

The target audience, safely distanced by thousands of miles but tethered via live webinar, included two dozen United States-based specialty coffee roasters, cafe owners and buyers, each of whom has demonstrated a commitment to equitable, transparent and direct trade with farmers.

The tasters had previously received mailed boxes containing 50-gram packets of Lao coffee beans collected by the CLEAN project in Laos from three coffee cooperatives: Bolaven Farms, Jing Jhai and the Bolaven Plateau Coffee Producers Cooperative.

The packages contained 16-page booklets describing the CLEAN project and its market linkage goals; the history and composition of the coffee co-ops; and details of each of the coffee samples, including cultivars, farm elevations, and facts about the farmers and their growing and processing practices.

A strong score from any of the influential sniffers and sippers in the online group could go a long way toward helping raise the profile of coffee in Laos — the small, landlocked nation squeezed between the larger, better-known coffee-producing countries Thailand and Vietnam — or even help seal new export deals.

The U.S. coffee market is, after all, the world’s largest, with imports totaling more than $4 billion per year and rising. Why shouldn’t Lao coffee farmers benefit if they have good coffee?

A major hurdle, especially in this era of pandemic-related travel restrictions, is getting Laos’ unknown coffees into the cups and under the noses of prospective buyers to score them.

Ordinarily, high-end specialty coffee buyers, particularly those interested in sourcing single-origin beans, like to travel to the source to assess new coffees, to experience the region and culture, and to get to know the producers. CLEAN and CQI pitched the virtual cupping as an experimental workaround, receiving strong interest from U.S. buyers, as well as Lao producers and cooperative leaders.

The coffees were originally expected to be cupped at the 2020 Specialty Coffee Expo in Portland, Oregon — where USDA funds were also set aside to allow Lao coffee farmers to travel to the Expo — although that event was of course canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

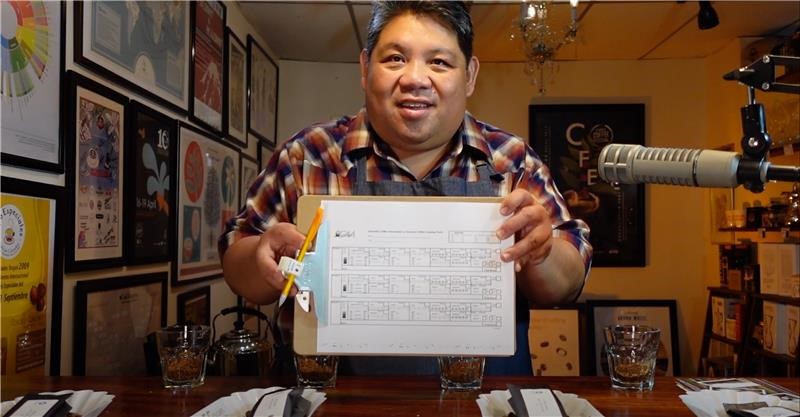

Jay Caragay, owner of Spro Coffee in Baltimore, cupped the Lao coffees while sharing the results through his YouTube channel. Screenshot.

“Farmers are crucially in need of new export opportunities, and I hope we can count you among those in the near future,” CLEAN Chief of Party Alex Dahan said in his opening remarks in the “Taste of Laos” virtual cupping. “We are thrilled to be working once again with CQI, with whom Winrock worked in Myanmar for nearly five years on a successful USAID project, with stunning results. We are working together again with some great local coffee farmers in Laos to bring you some very special coffees today.”

In between cuppings and shared sensory evaluations, the event also allowed roasters to hear directly from coffee growers about cultivation practices and common problems, while sharing their hopes for the future.

“Coffee is the main crop, the main income for the villagers,” Laty Keopiensy, co-founder of the Jing Jhai Coffee cooperative, said in a pre-recorded video from Jing Jhai’s cozy cafe in downtown Paksong, from which all profits go into sanitation, education and clean water projects for children in the coffee-growing communities.

In the end, most of the participating roasters and buyers said the interesting, fruity flavors and overall quality of the coffees prompted them to consider adding Lao arabica to their offerings. Several posed logistics and other practical questions about how to find and import the coffees, which CLEAN and CQI will address with producers. They encouraged CLEAN and its partner co-ops to keep the momentum going by organizing an annual, nationwide cupping competition, among other activities.

While the pandemic has caused much of the coffee world to shift to virtual settings, the hope is that Lao arabica can become a reality for many buyers, much to the benefit of producers and consumers alike.

Timothy D. May

Timothy D. May is a senior content manager for Winrock International.

Comment

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

i have an unknown single estate farm high in the Jamaica blue mountains

Blue Mahoe Estate 100% Jamaica blue mountain coffee

It is grown and processed in tve tradditional way with astounfing results

Would you line to cup

Traditional Lao Coffee is the real Lao coffee. You can buy a kilo of Coarse Grind Traditional Lao Coffee at the Kua Din Market behind the Talaat Sao in Vientiane. It costs 50,000 KIp, or US$5.20. Is prepared by pouring hot water through a cloth bag into a large metal cup. Allowed to steep a little and usually is poured through the bath again.. It is very strong, but delicious with sweetened condensed milk and a Lao breakfast. Usually is served in a small glass where you can see the layer of milk on the bottom. I love it.