[Editor’s note: The following story highlights a collaborative study released earlier this year called “The potential for income improvement and biodiversity conservation via specialty coffee in Ethiopia.” A lead author of that study was Pascale Schuit of Union Hand Roasted Coffee. An version of this story first appeared on the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, website. It has been adapted and republished here with permission.]

While the coffee sector has in many ways taken a leadership role in environmental sustainability, coffee farming continues to be a major cause of deforestation and biodiversity decline in tropical countries, from the Americas across the tropical belt to Australasia.

In some regions, the negative consequences of coffee production are worsening as the global demand for coffee increases.

Coffee and sustainability

The recent report Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review stresses that our relationship with the natural world requires fundamental change.

It argues that human societies could live sustainably by ensuring that the demands they put on nature do not exceed its resources.

Coffee farming is an example of how we need to change the way we grow our crops.

Instead of destroying natural habitats, it could serve to preserve forests and biodiversity, sustain beneficial ecosystem services, fix carbon, improve degraded landscapes, and provide a sustainable livelihood for farmers.

One of the difficulties of quantifying the impact of coffee farming on the natural world, both negative and positive, is the paucity of reliable data and research products.

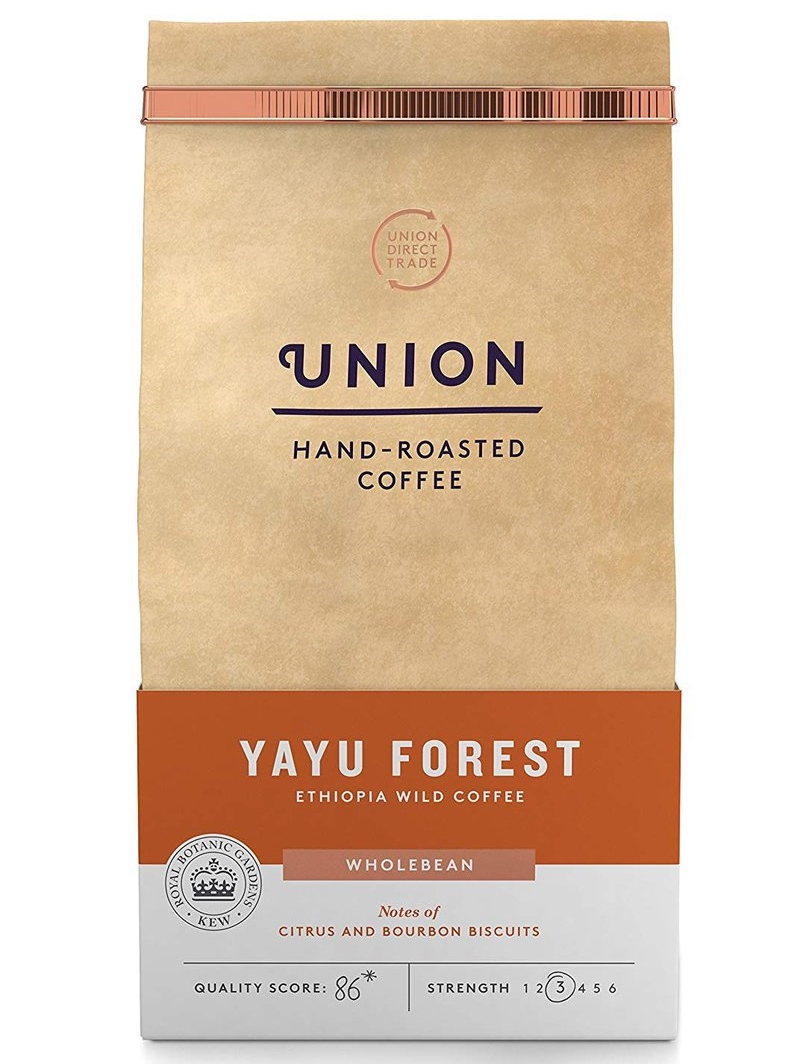

In 2014, we at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, began a project in the Yayu Coffee Forest Biosphere reserve in Ethiopia with the UK roasting company Union Hand-Roasted Coffee, to better understand the synergy between coffee farming and biodiversity, with the aim of gaining a more detailed understanding of the coffee supply chain (often referred to as the value chain).

Ethiopian coffee

The coffee sector is a multi-billion industry.

In Ethiopia alone, coffee provides about 25% of the total export earnings, and supports the income of an estimated 15 million people.

The humid, tropical forests of Ethiopia and neighboring South Sudan are the natural (wild) home of Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica).

These forests exist in a natural or semi-natural state, and some have been designated as reserves for the conservation of nature and livelihoods.

Home to large numbers of other plants, animals, and fungi, the forests play a key role in providing a livelihood for the people that live in and around them.

The Yayu Coffee Forest Biosphere Reserve is noted for its particularly high levels of natural (wild) Arabica coffee genetic diversity.

In its core area, the Yayu forest remains intact and largely undisturbed with many thousands of wild coffee plants mixed with other wild vegetation.

The actual coffee farming occurs at the forest edges and transition zones of the reserve, where it provides up to 70% of the cash income for over 90% of the local population.

Specialty coffee

In our recent study, we looked at the potential for income improvement and biodiversity conservation via specialty coffee.

Specialty coffee is a high-quality product, which like fine wine, commands higher prices.

Over the last two decades, demand for specialty coffee has increased and continues to grow.

Its higher quality status is achieved by implementing best-practice farming, harvesting and processing methods, and high levels of quality control.

In an ideal model, the extra income generated by speciality coffee is distributed throughout the supply chain, including the coffee farmers.

In the study, we found that even moderate participation in the specialty coffee market positively influenced income for the smallholder coffee farmer.

If farmers sold just a proportion (c. 25%) of their harvest for use as speciality coffee, their annual income from coffee increased by 30%.

Based on these findings, we projected a scenario where, if farmers were to sell all their harvest as speciality coffee, their income from coffee could increase by 120%, although this would require optimum operating efficiency of their farms and the cooperatives.

In both cases, the additional income was achieved by receiving a higher price for the coffee.

Due to a dramatic increase in the quality of the coffee, brought about by interventions undertaken during the project, the price achieved was $2.80 per pound, twice the Fairtrade minimum price paid for Arabica coffee at that time.

Importantly, the increases in income via speciality coffee were achieved without the need for more land, or increased inputs, such as artificial fertilizers, irrigation, herbicides and pesticides.

Once sold on, the Yayu Forest project coffee was purchased in sufficient volumes for it to be placed in two major UK supermarkets (Sainsbury’s and Waitrose), and sold at Kew retail outlets and online.

Between 2015 and 2018, a total of £924,751 (approximately US$1.26 million) of speciality coffee was purchased from across the five Yayu cooperatives, much of this constituting additional revenue for the community.

Yayu Forest Coffee is now in its seventh year and continues to sustain strong consumer demand.

The 20 cents per pound forest conservation premium, which has been translated into a 34-cent donation (per pack) of retail coffee, goes to the Yayu community and ongoing research.

Environmental monitoring

Another key element of the study was to demonstrate that the coffee being sold as Yayu Forest Coffee was actually associated with forest.

Using satellite imagery, we were able to show that the Yayu coffee farms had tree cover levels and canopy health approaching undisturbed, wild forest.

In addition, we were able to show that the Yayu area has undergone only minimal deforestation over the last two decades.

Sustainable sipping

While the aspirations of biodiversity conservation and agriculture are often in contradiction, there can be common ground, to provide opportunities for both biodiversity preservation and livelihoods from farming.

We have made progress in understanding and developing the value chain in Yayu, in such a way that supports and sustains these relationships.

While even the most sustainable forest coffee production can have some negative environmental consequences, they are substantially less impactful than many types of coffee farming, such as those involving recent, wholesale deforestation, and large-scale monoculture with environmentally harmful inputs.

The problem for the consumer is that they have no means of understanding the environmental impact, good or bad, caused by their purchasing choices.

A good starting point would be for consumers to have more awareness of how their purchasing decisions actually impact the natural environment thousands of miles from where they sip their morning coffee.

For example, we now have the technology to add environmental metrics, such as the amount and quality of forest cover where a coffee was grown, to individual bags of coffee.

Aaron P Davis

Aaron P. Davis is the Senior Research Leader of Crops and Global Change, and Head of Coffee Research at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Comment

3 Comments

Comments are closed.

I’ve been in the specialty coffee extraction business for many years, providing high grade liquid coffee extracts as a food flavoring to RTD coffee beverage manufacturers and ice cream producers to name a few.

Since we do not hydrolyzes any cellulose in the process, we have 20 tons of dry spent coffee grind waste per shift resultant from the process of extraction.

Basically coffee beans are about 85% wood fiber and 15% flavor and fragrance removed as extractables.

May i suggest that spent coffee grinds be used as a biomass boiler fuel to heat process water and meet factory heat needs, with the resultant ash ( about 1.5% wt/wt) be shipped back to the country of origin to be used as an organic fertilizer.

Basically, every 100 shipping containers of green coming from country would result in 1.5 containers of soil nutrient specific to the needs of coffee plantations.

When wood is burned, the resultant ash contains all the nutrients, since only the carbon is burned.

Vast amounts of green coffee are turned into extracts for many uses, factories like mine could become much more “in balance” if such recycling could be promoted

Great idea, you’d have to find a carbon friendly way of shipping the ash back, but yeah, every time you take a cherry from the tree, you are stealing nutrient from the soil.

Definitivamente , estos artículos quieren soslayar el hecho de que el 90% de los CAFICULTORES en latinoamerica, son pequeños productores; por consiguiente están sometidos al juego infame de los intermediarios en el mercadeo de su producto. Solo será posible implementar unos cultivos amigables con el medio ambiente, cuando los cultivadores tengan un precio retributivo verdaderamente digno. El negocio del café , empieza a partir de los intermediarios; el productor aguanta hambre si solo vive de su cultivo.