[Note: This is Part 2 of a short series of stories by guest author Jonas Ferraresso exploring some of the intricacies of the Brazilian coffee market and Brazil’s outsize influence on the global coffee trade. Find all the stories here.]

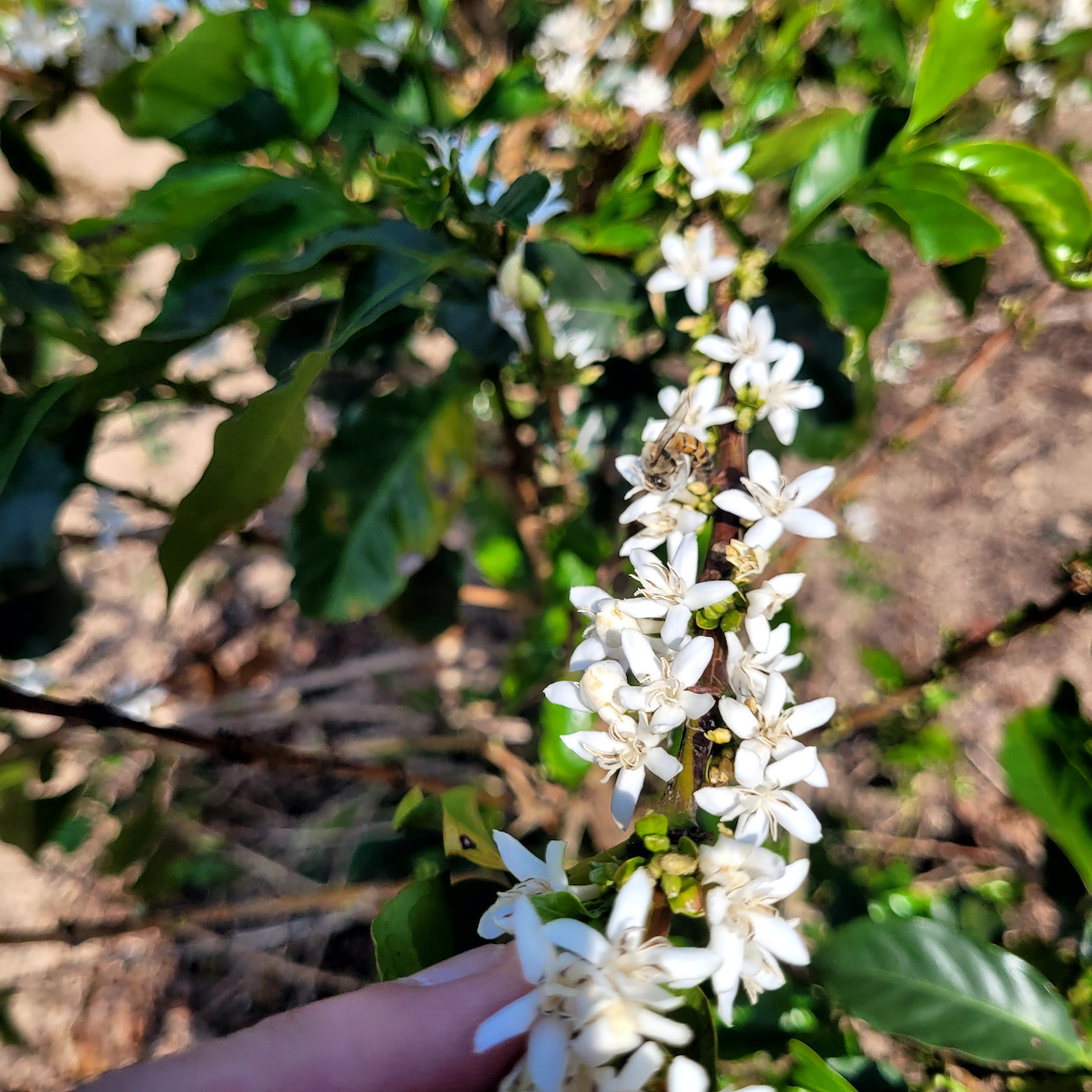

Coffea arabica (arabica) and Coffea canephora (robusta) are two plant species integral to the daily lives of billions. Together, they account for nearly all global coffee consumption. I say “nearly” because other coffee species are also consumed, though primarily in their regions of origin.

While drinking coffee feels like a natural habit, it’s also a daily decision-making process. Each consumer has unique preferences, seeking attributes like flavor quality, stimulation or affordability. These choices influence much more than an individual’s morning routine — they drive coffee production and research efforts on a global scale.

For over a century, researchers in Brazil and elsewhere have worked to meet the demands of the industry. Their focus has been on everything from innovative cultivation methods to the genetic improvement of coffee plants. While the term “genetic improvement” might sound technical, the concept is straightforward: selecting and developing plants with traits beneficial to the coffee sector.

For instance, improving beverage quality involves identifying plants with beans that exhibit greater chemical complexity, higher acidity or more sweetness. Researchers may also seek plants with higher caffeine content or, for decaf, lower caffeine. They may also prioritize plants based on their potential production volume per area.

However, genetic improvement tends to look beyond these individual attributes, instead seeking to combine the ideal mix of each of them in a single plant.

This work is neither quick nor cheap. Developing a new coffee variety often takes decades or even generations of dedicated research. Popular market-ready varieties like Bourbon, Geisha, Caturra and Arara are the culmination of years of scientific and agricultural effort.

The Untapped Potential of Other Species

While nearly all the world’s traded coffee comes from Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora, the Coffea genus includes at least 128 other species that remain largely untapped.

These species — such as Coffea liberica, Coffea racemosa, Coffea stenophylla and Coffea eugenioides — hold immense potential for future coffee breeding programs.

Coffea stenophylla is a particularly notable example. The West African species, cultivated in countries including Sierra Leone, gained attention in 2021 for its high-quality flavor and tolerance to heat and drought — traits that have become increasingly vital in the era of climate change. In Brazil, the Agronomic Institute of Campinas (IAC) has studied stenophylla for decades.

So, why hasn’t Coffea stenophylla become a commercial crop? There are several reasons. First, the species is not resistant to coffee leaf rust, a devastating fungal disease. Its productivity is also lower than that of current commercially grown varieties, making it less appealing to farmers. Additionally, the costs and risks of planting new coffee fields — which may take four or five years to bear fruit — deter widespread experimentation among farmers.

Climate Change and the Challenge of Adaptation

As climate change disrupts coffee production in Brazil and other regions, the industry faces a stark reality: no immediate or short-term genetic solutions exist.

Developing a new variety suited to today’s climate challenges could take decades. In the meantime, farmers and researchers must rely on management strategies. These include adopting proven varieties and implementing practices like regenerative agriculture and agroforestry systems, which require significant investment, regional studies and producer training.

It is important to note faster and more efficient genetic research methods for coffee cultivation currently exist, although traditional methods such as cross-pollination and selective breeding have historically had the most reliable results.

A New Phase in Coffee Research

However the next era of coffee breeding research unfolds in Brazil and beyond, it will reflect the industry’s changing priorities.

Early efforts focused on increasing production, then boosting productivity, followed by resistance to pests and diseases, and more recently, enhancing quality. Now, the most pressing challenge is to develop varieties capable of withstanding climate change.

This is no longer about producing more coffee or improving its flavor. It’s about ensuring coffee’s survival. Without urgent innovation and investment, the future of coffee as we know it could be at risk.

Publisher’s note: Daily Coffee News does not engage in sponsored content of any kind. Any statements or opinions expressed belong solely to the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Daily Coffee News or its management.

Comments? Questions? News to share? Contact DCN’s editors here. For all the latest coffee industry news, subscribe to the DCN newsletter.

Related Posts

Jonas Ferraresso

Jonas Leme Ferraresso holds an agronomy degree from São Paulo State University (UNESP). He has worked as a coffee farmer, a coffee agronomist and as an advisor for several farms in Brazil.

Comment