by Michael Sheridan of CRS Coffeelands Blog

This is the second in a two-part conversation with my friend “Alex,” a respected colleague in coffee, that explores the opportunities, limitations and impacts of microlots. Read the first part here.

ALEX: Are microlots a better alternative for livelihood resilience than diversifying farm production?

MS: In general, I would say no. But some of the data we have collected in connection with our Borderlands project in Colombia suggests that under some circumstances, it may be.

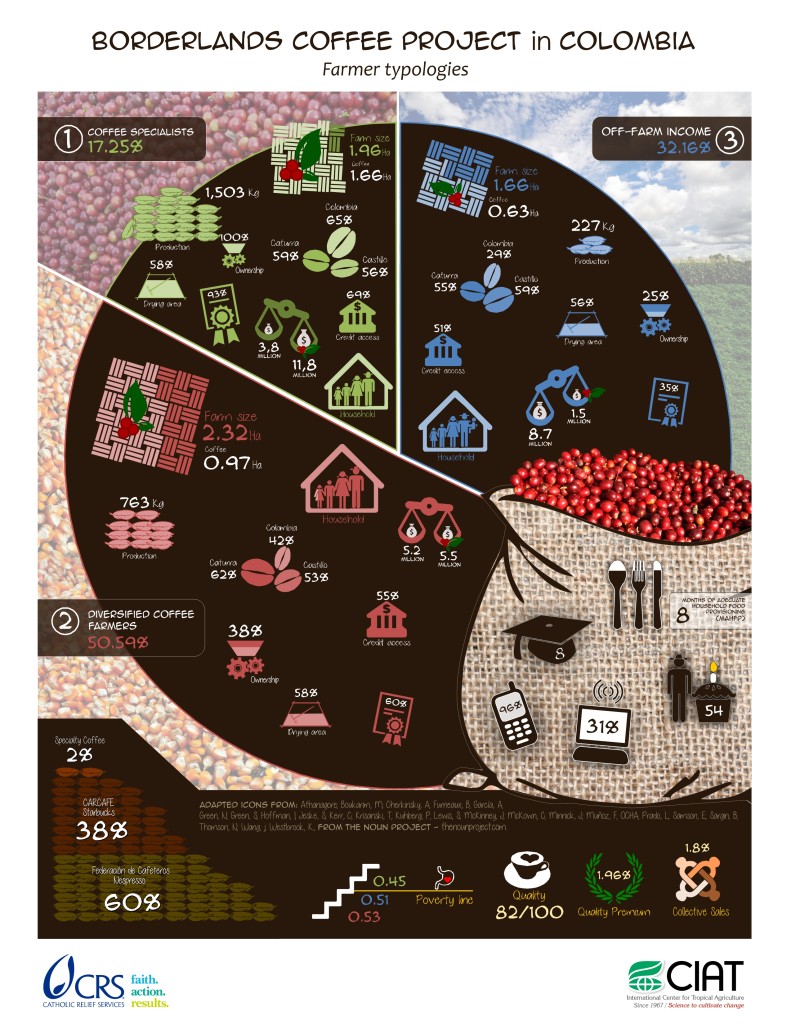

The baseline survey we conducted in Nariño helped us to identify three different types of coffee growers on the basis of the degree to which they rely on coffee for income: specialized coffee farmers, diversified farmers, and rural dwellers who derive most of their income from off-farm activities. This infographic compares the three farmer types across a range of demographic and economic variables:

The data show that specialized coffee farmers had the highest incomes, highest indicators of food security and highest rate of educational attainment. In other words, they suggest that the kind of specialization required to achieve microlots is in fact associated with better livelihood outcomes.

That is a challenging finding given how much energy we have collectively devoted to the (intuitively appealing) idea of farm diversification and investment in producing food crops to help address the issue of seasonal hunger in the coffeelands.

It is important to point out that this and all my other answers to all your questions are highly contextualized and informed by data we have collected and analyzed in connection with the Borderlands project I lead in Nariño, Colombia, a place where extraordinary coffee quality and exceptional farmer support systems may make it a somewhat less-than-representative origin. The specialized coffee farmers here are concentrated in the La Unión region which is the source of two of every three pounds of coffee produced in Nariño. It has attracted an extraordinary amount of attention and investment from Colombia’s coffee insitutions, meaning that specialized smallholder coffee growers there are much different from specialized smallholder growers in places where the policy environment is less enabling for the coffee sector. The responses to questions like this one could very likely be quite different in other places where we are implementing projects in the coffeelands.

Even more important is recognizing that this is a snapshot based on data from one year. It doesn’t take into consideration market volatility over time. In the event that prices were to return to 2001 levels, or if there were to be a resurgence of the coffee leaf rust epidemic, diversified farmers may indeed be more resilient — less poor and less hungry — than specialized coffee farmers whose well-being is more dependent on coffee income. In summary, I would not be comfortable advocating in any generalized way for microlots over farm diversification as a resiliency strategy until I saw similar data from lots of other origins.

ALEX: Do microlots present risks, economically and socially, to a producer and a community? For example, earning 4x more than your next door neighbor because you scored a microlot deal one year and she didn’t – and then the tables are turned the following year – can these windfalls have unintended community repercussions?

MS: This is an important question, and one that our friends at Counter Culture have studied in much greater depth than we have. I am sure you have seen the extraordinary study on the social impacts of microlots the company did years ago in Peru, which was predicated on concern for precisely the kinds of social conflict you allude to in your question.

We have discussed that work with Counter Culture in great detail. And we have been mindful of the risk of social conflict in advancing the microlot model and working to help farmers organize around quality for the marketplace. In fact, I would say we have been acutely aware of this risk because we work in so many communities in Colombia where the social fabric has been stretched, if not torn, by armed conflict; we are determined to contribute to building social capital, not tearing it down. And we are, as you will see in my response to your next question, measuring farmers’ perceptions of fairness in trading relationships.

Fortunately, we have not seen this dynamic devolve into social conflict or disunity. But that is not to say it is not without its challenges. We have had individual growers try to sidestep the community-level processes as soon as their coffees were earn microlot premiums, and had to work hard to bring them back into the fold with conversations very similar to the conversations we are having here. We try to explain, with the help of members of the project’s Advisory Council, that a strategy built on single-farm lots isn’t likely to generate much impact or get very far. We advance the counter-intuitive argument that single-farm lots are only possible after we nail down the process of building community lots, since it is precisely that lot-building and segmentation discipline that enables farmer organizations to identify lots that would qualify for microlot premiums. It hasn’t been easy, but so far the center is holding.

I think part of the reason is that the disparity in prices isn’t as dramatic in practice as the “4x” and “windfall” references in your question may suggest. As I explained here yesterday, our approach means that some growers will get microlots while others don’t, but all growers will have a chance to earn some quality premium. When the approach works, growers get some premium every year even if it is not a microlot premium, which keeps people interested in continuing to apply the approach..

ALEX: Is microlot pricing fair and transparent (and therefore replicable)? Or is it too highly subjective?

MS: Funny you should ask. About the fair and transparent bit, that is — we just gathered data on this topic for the first time.

After we closed our CAFE Livelihoods project closed in Mesoamerica back in 2011, I was frustrated by our inability to report out with more rigor on changes in grower perceptions of transparency and fairness, and began searching for ways to that. Over three years of work in Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua, we built a vast dataset with metrics on yields, sales, income and other key perfomance indicators for over 4,000 households. We could speak to those outcomes with some level of rigor. But in describing what I considered the most important impacts of the project — the qualitative improvements we helped to facilitate in trading relationships — we were reduced to anecdotes. Story-telling. The journalistic treatment you often see in text boxes in documents that are otherwise dedicated to more robust data analysis.

Fortunately, this groundbreaking guide to measuring fairness in trading relationships, the LINK methodology we have been applying together with CIAT in the context of our Borderlands project, and the powerful new SenseMaker technology are giving us some tools to narrow the gap between the qualitative and the quantitative. More precisely, they are allowing us to quantify the qualitative — to make statistically robust correlations among the “micronarratives” that used to be consigned to text boxes.

I tried to get some of the preliminary data ready in time for this post but couldn’t get them to a point where I was comfortable presenting them. When we have done more analysis we will surely share the results here. Meantime, what does seem clear from even a preliminary assessment of partial data is that growers in Nariño who apply the microlot approach successfully have different perceptions of fairness and transparency in their supply chain relationships than those who do not.

In response to your second question, I would say that everyone working on the Borderlands project would agree with that the process by which microlots are identified is still the source of confusion among growers. In fact, the word most we use most commonly to describe farmer perceptions of the procss is “mystifying.” Much of the visit of our Advisory Council this summer will be devoted to explicit efforts to “demystify” the process through intensive and direct interaction between roasters and the growers from whom they are buying coffee. A lot of this has to do with a gap in sensory capabilities but a lot of it is just a function of transparency: how the business works, what it looks for, how it makes decisions, the constraints and opportunities it faces in the marketplace that inform its decision-making at origin, etc.

This year, the first decisions being made about which lots will qualify and which lots won’t are being made by members of the community whom the project has trained as sensory analysts. Relying on community analysts who are fully dialed-in on the approach and moving that initial decision-point into the communities for the first time will help, although we expect it will take several years until the approach is fully digested at the community level.

ALEX: What effect, if any, do microlots have on prices for other qualities from the same region?

MS: On one level, I think I addressed this question in some detail yesterday. While microlots may fetch the highest prices, they tend to be, as their name suggests, very small. The real economic impact of a microlot approach lies in the larger volumes of lower-grade coffees (AAA, AA, A) that may not make the cut for microlots but still qualify for more modest premiums. The microlot prices anchor that quality hierarchy; the prices microlot buyers pay for other qualities in the same region are set against the microlot price. But that refers only to the growers who are connected to buyers in higher-value segments of the market, and only refers to coffees that have been separated on the basis of their quality.

On another level, I think it is fair to wonder whether introducing microlot prices in a conspicuous way in communities where they have been mostly absent has the potential to affect prices more broadly, even for coffees that are not being traded in the context of a microlot approach. In the case of Nariño, the volume of coffee the project has helped bring to market through the microlot approach is still exceedingly modest. Even combined with the coffees that were already being sourced directly from Nariño when our project started, we are not talking about enough volume to really influence the local market price. If there is a quality-oriented initiative affecting the price of coffee in Nariño, it would be more likely to be the Denomination of Origin work led by the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros than the small-but-growing segment of quality-differentiated coffees.

While this work may not have not had any discernible impact on prices in Nariño beyond those earned by participants in our Borderlands project, it may be skewing the expectations of other growers in the region around price and price discovery. That may be a topic for another conversation.

ALEX: Do microlots actually incentivize and properly reward production of specialty coffee over the long run for smallholder producers? Or is that just something that specialty coffee wants to believe?

MS: A good one to close on. Are the narratives we use to promote microlots self-serving? A convenient storyline that aligns prevailing sourcing practices with positive social impact at origin? A kind of social greenwashing? Or are they based on something real and durable? I think we need to acknowledge that you are asking the right question, and that no one has really provided robust evidence to answer it. I will be able to respond with data from Nariño as long as we have project funding to continue collecting and analyzing them, but then what? Who will take on that task? And if it is an industry actor, how can we ensure the credibility and integrity of the research they conduct is not compromised by commercial interest? As industry invests more in scientific research through collective-action mechanisms like World Coffee Research, I believe there is also an urgent need for investment in independent “social research” on issues like this one.

Today’s conversation with “Alex” was the second in a two-part series. Read the first part here.

Michael Sheridan

Michael Sheridan is the Chief Executive Officer of the Coffee Quality Institute, a nonprofit organization with a mission to improve coffee quality and the lives of those who produce it. Sheridan has been leveraging market forces to make coffee work for smallholder farmers and farm workers since 2004. Most recently he directed progressive green coffee sourcing activities and direct-trade partnerships at Intelligentsia Coffee. Prior to that he worked to deliver initiatives in the coffee sector in Central and South America on behalf of Catholic Relief Services.

Comment