The specialty coffee industry relies heavily upon the trained and calibrated palates of certified Q-graders and professional tasters, while sensory experts have made important gains in recent years in attempting to unify the language used to describe coffee and its complex, interwoven qualities of flavor, aroma, feel and finish.

The extent to which the coffee world’s largest commodity-grade goliaths depend on these very human methods is hard to know, though we do know that it’s not solely a legion of experienced, pink tongues that they depend upon.

At the upcoming SCA Expo event in Seattle, the U.S. specialty coffee industry will get its first glimpse at one of the more advanced solutions applicable to massive-scale coffee blend production and quality assurance: The Insent TS-5000Z Taste Sensing System, also known in the sensory analysis world as an electronic tongue, or e-tongue for short.

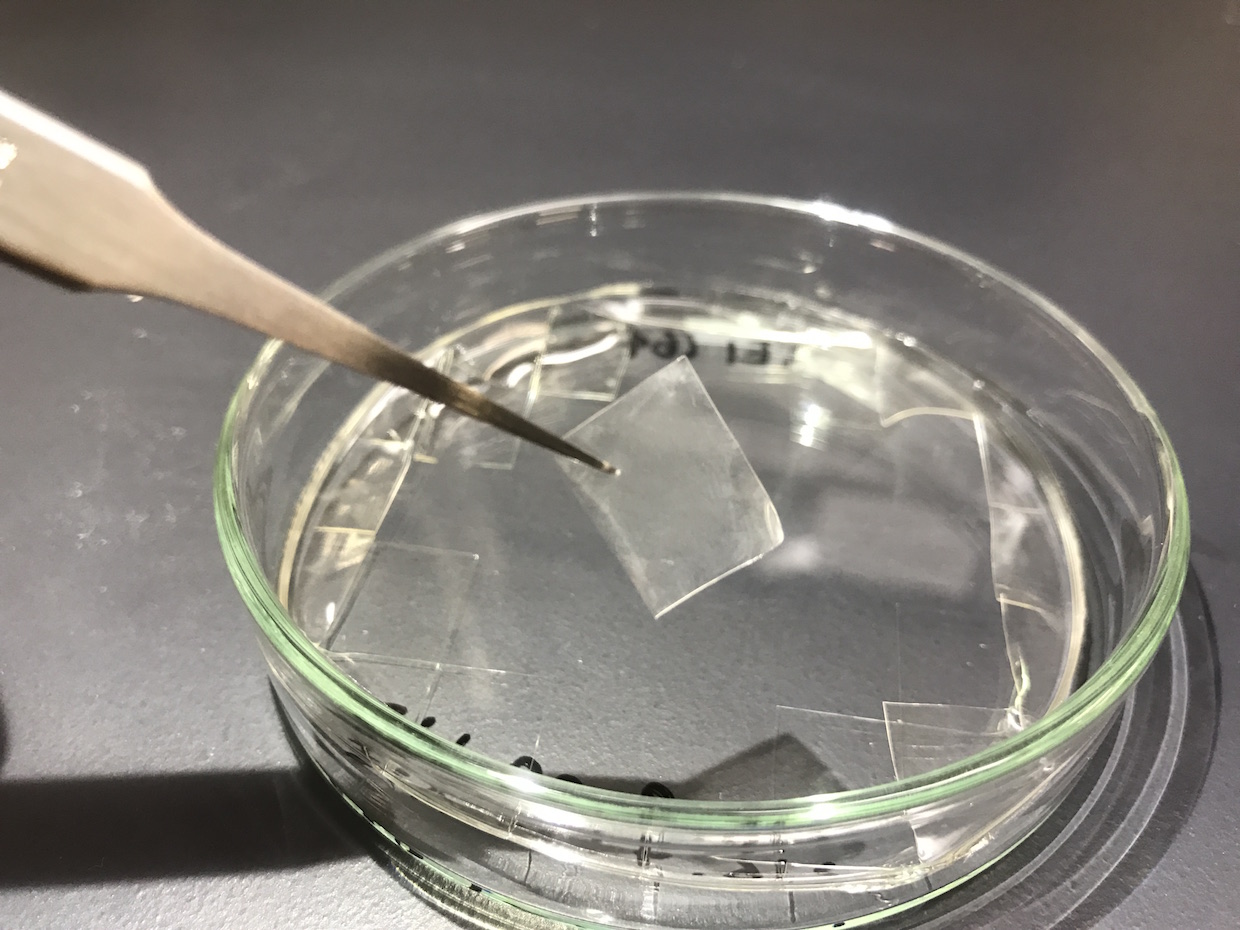

This particular electronic tongue is composed of a group of individual sensors that contain fluid that’s held in by artificial gelatinous “lipid polymer” membranes. An electrode is also embedded within each sensor. Another group of sensors with glass membranes functions alongside the lipid polymer group, as a reference. All of the sensors are lowered by the machine into cups containing the fluid to be analyzed.

Each lipid polymer membrane is engineered to be affected only by a particular compound. As those compounds are absorbed by the membranes, it changes the reading from the electrode inside the sensor, while readings from the reference electrodes behind the nonabsorbent glass membranes remain the same.

The machine measures the difference between the two sets of sensors and translates that data into both numerical and visual values, with which an accompanying software package makes charts and graphs and performs relevant calculations on demand. The compounds measured by these tests are those that create the five fundamental tastes of bitterness, sourness, sweetness, umami, and salt.

“The lipid membrane is similar to what your tongue is made out of. In essence, you can just call it an artificial tongue,” Higuchi Inc. Los Angeles Branch Manager Mikio Morinaga told Daily Coffee News. “That’s how a person also senses flavor. It’s by an electrical signal coming from your tongue into the brain.”

Higuchi is the stateside distributor for Insent Intelligent Sensor Technology Inc., manufacturer of the e-tongue. Morinaga said that the technology has been in use for decades, primarily in the pharmaceutical industry in the development of masking agents for drugs in preparation for human trials, because drugs are always unpalatably bitter. Yet for almost as long, large-scale food manufacturers have also adopted the technology for R&D and quality assurance purposes.

“It will not replace human sensory in a full-body way, because a person also uses aroma to define a taste. So it won’t get into gourmet wine or coffee, where they say ‘ah, there’s a hint of cherry’ or that kind of definition of flavor,” said Morinaga. “It drops the definition down into more simplified categories. However, that sensitivity is designed to match a human’s sensitivity.”

By the latter part, Morinaga refers to how, while the electronic sensors technically read the presence of compounds in parts per million, it translates that data onto the scale of human perception. The human palate has evolved to be far more sensitive to bitterness than sweetness, for example, because bitterness signals toxicity, or sourness might indicate spoilage, and so on, providing indicators of things humans might not want to eat in the wild.

Therefore, through the e-tongue’s interpretive software, a very slight presence of bitterness in ppm would be a high reading, whereas higher ppm of a sweetness compound would not be read as quite so perceptible.

Research and development of taste sensing technology began in Japan in 1989, leading to the first generation of machinery in 1993. The latest iteration of the TS-5000Z has existed since 2007, and in the coffee industry, Morinaga said that the biggest-of-the-big companies use it in developing blends, adjusting them according to seasonal availabilities and cost concerns, and monitoring them for consistency. Taste sensing software records sample data and can then compute how much of one stored profile is needed to combine with another in order to achieve a specific result.

In a complete R&D cycle, a human panel might do tastings in the beginning and then again at the end of development, while comparative developmental analysis of a given blend or product could be conducted via e-tongue in making adjustments along the way. The device could also be used to analyze a competitor’s product, for the purpose of either imitation or differentiation.

Said Morinaga, “We have quite a bit of track record with coffee companies in Japan, so we know it works.”

The TS-5000Z is not the kind of thing that would find a place in the roastery lab of a company that prides itself on the artisanal, hands-on, small-scale manufacturing of an ongoing series of unique, high-end seasonal offerings. At $125,000 for delivery, installation and training, it would also not likely find a place in the budget of such a company.

Yet for the major players of mass-production on a scale that would exhaust a battalion of human palates, the TS-5000Z serves a fascinating purpose, and it will be on display at the upcoming SCA Expo for those interested in learning more.

Morinaga said that demos at the show would be impractical due to the four to five hours it takes to complete the analysis of a set of 10 samples. However, flyers and personnel will be available for information.

Howard Bryman

Howard Bryman is the associate editor of Daily Coffee News by Roast Magazine. He is based in Portland, Oregon.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Dear Sir/Madam,

I am interested in this TS-5000Z ‘Tastes’ Mass equipment.

Could you please share the tech. information and price?

Thanks and best regards,

John