Cherries ripen and await the final passes through the farm on Finca Un Regalo de Dios. Photo by Carabello Coffee.

Two weeks ago, I was part of a small group of people sitting in a tiny room the on the property of Finca Santa Teresa in northern Nicaragua. As I have done for each of the past four years, I was enjoying some savory cookies and coffee straight from the farm, provided to me by its gracious owners, Joaquin Lovo and his wife Marielo.

This is always the moment when touring one of Joaquin’s farms that I look forward to — a time when we talk of the past harvest, and of what he is preparing to do for next season. This year, the conversation took an unexpected turn.

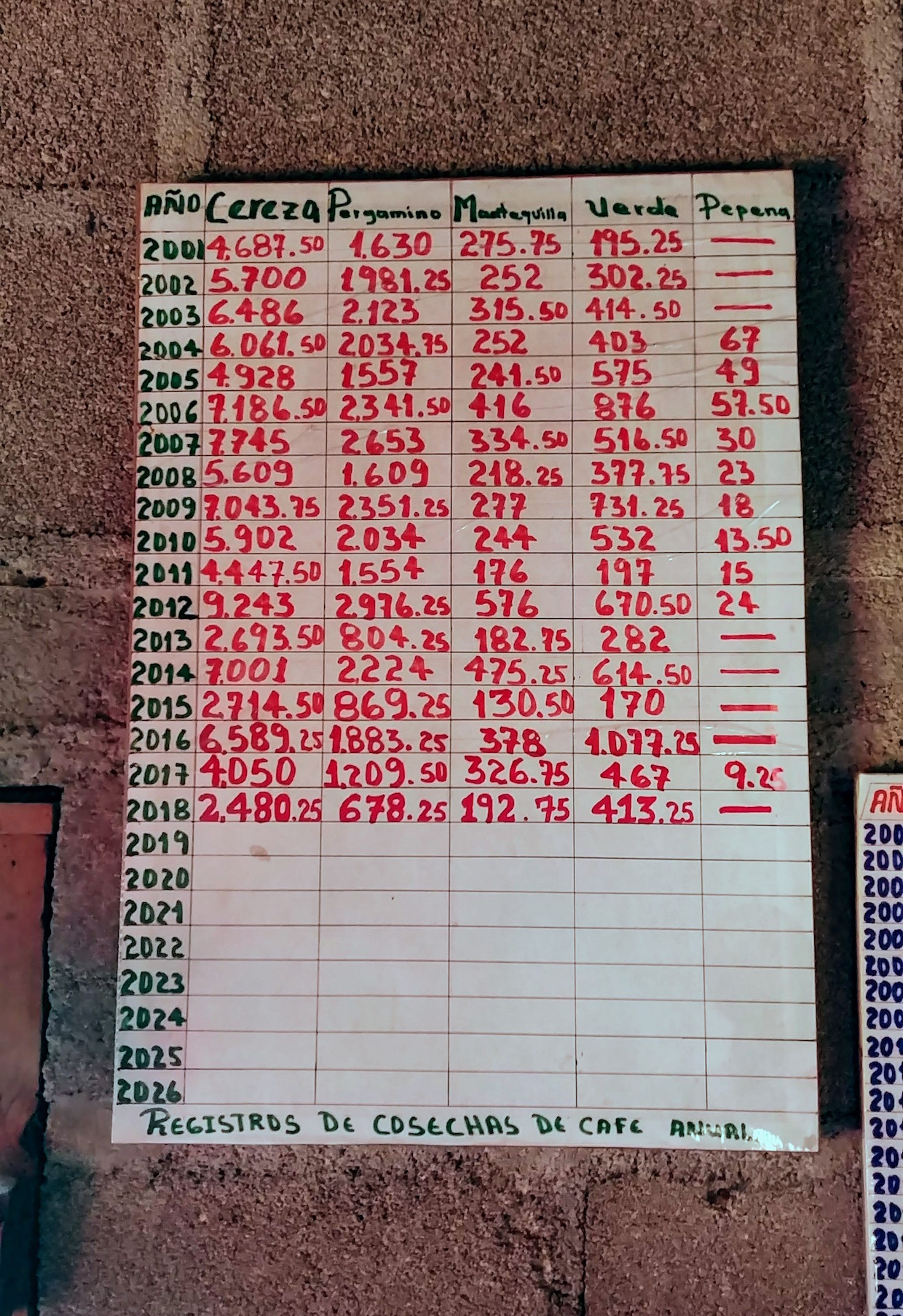

This chart hangs on the wall of the farm manager’s office on Finca Santa Teresa, owned by Joaquin Lovo. On it he has measured each of his harvests since 2001. On the left he tracks the weight of harvested cherries in quintales. As you can see, this is his lowest production in that time, with production only dipping below 4,000 quintales only three times. The harvest this year is the lowest it was ever been, coming in at 61% of last year’s and at only 37% of what it was two years ago. Photo by Carabello Coffee.

On the wall hangs a chart where Joaquin’s farm manager has been recording data from every harvest since 2001. This year marks the smallest harvest during that time, and a nearly a 50 percent drop from last season. Joaquin made it abundantly clear that this downturn is not unique to this place; in his words, “it is the same in every farm” in Nicaragua.

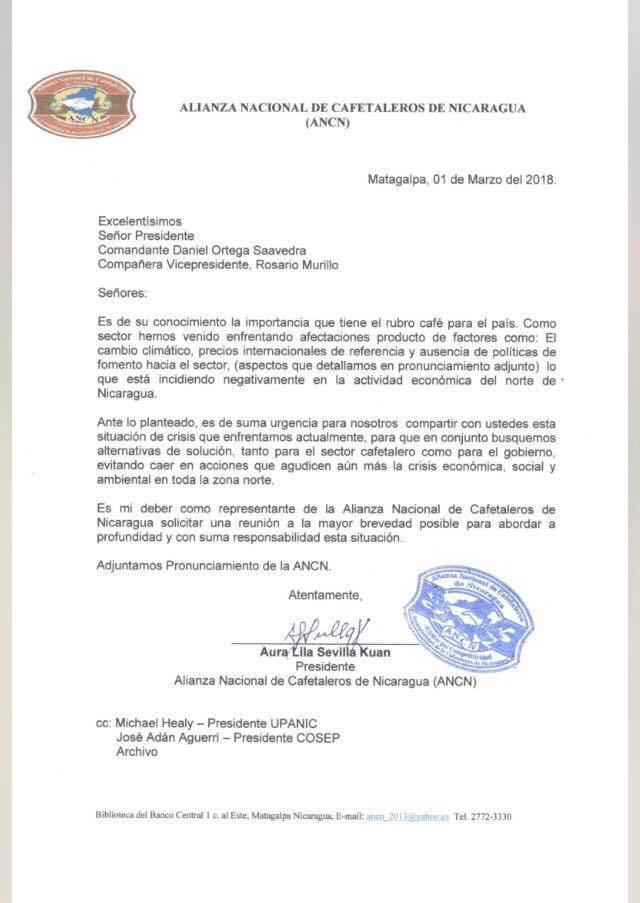

Next, Marielo pulled out a letter and began to read. The letter was sent to President Daniel Ortega in early March by Nicaragua’s National Alliance of Coffee Growers (ANCN). In it, they detail a mounting crisis, cite the impending danger of many farmers losing their bank financing, and ask for immediate, financial assistance. La Prensa has more on that group’s efforts.

When Marielo finished reading, we sat in silence for a while, considering the weight of what we had just heard. For the next two days, as we visited with the two other producers we work with — Luis Alberto Balladarez and Jamir Garcia — the prognosis was the same: There is a coffee crisis in Nicaragua.

Marielo Lovo, wife of Joaquin, shares the concern farmers in Nicaragua have regarding their government’s lack of investment or subsidy in the coffee sector with some of our wholesale clients. Photo by Carabello Coffee.

The Perfect Storm

In a typical year in Nicaragua, as the harvest comes to an end in late March or early April, the weather remains dry and hot until mid or late May, when the rains come. This is good for the coffee plants, as it produces stress that results in strong flowering for the next year’s production and allows the flower to produce fruit before the rains come. But last year, as the harvest came to an end, the weather remained unseasonably cool, and the rains came early.

This was bad for two reasons: The lack of that stress period resulted in fewer flowers per plant, and subsequently less fruit, than in a normal year; and then, the early rains knocked off a high percentage of those flowers before they could produce a cherry.

Luis and his son, Luis Jr. (left), take a moment to pause with the farm manager as we hike up Finca Un Regalo de Dios. Photo by Carabello Coffee.

The result, found throughout the country, was significantly fewer cherries per plant. Compounding the troubles were rains during the middle of growing period that caused some cherries to suddenly swell and then burst — much like a tomato when it experiences sudden, heavy rains — resulting in the beginning of fermentation and the loss of those cherries. Yet the cost of production remained the same as in a normal year, because the farmers must still care for the entire farm. For many farmers, this will mean a net loss for the year. And that’s just the beginning.

A Shortage of Labor

For reasons not fully understood, each of the farmers we work with said it was very difficult to find pickers for the harvest this year. When farmers do not have enough workers on the farm, ripe cherries go unpicked on the trees, resulting in further losses.

Luis’ shade canopy of natural/honey drying beds and processing area is impressive, as is the impeccable attention to detail his workers pay to the drying and sorting. Photo by Carabello Coffee.

During the year, Luis Alberto Balladarez employees roughly 100 people. But during harvest time, that number needs to soar to as high as 400 to meet the timely demand for labor. This year, Luis even offered significantly more money to pickers (this was verified by Joaquin Lovo), yet still could not attract enough pickers to work his farms.

The farmers attribute this to changing times, with young people increasingly less inclined to work manual labor jobs. As counterintuitive as it sounds, each of the farmers said that free internet in the public parks is also an issue, as young people of families who cannot afford the internet in their homes congregate to use the free Wi-Fi. The strong desire to have internet connectivity is enough to prevent many people from working in remote places, like coffee farms.

While this may be conjecture, the reality is that none of these farmers — some of whom are established and successful, having placed highly in high-profile international competitions in years past — had enough workers to pick their coffee during the harvest.

Credit Problems

While I was visiting one of the farms, a bank inspector arrived. I could tell this was a tense moment for the farmer. Given the present conditions, the bank is concerned that he may not be able to repay his line of credit in full this year, and therefore the inspector was there to assess the health of the farm, and the potential for future credit.

After an extensive tour, the loan officer left saying that the farm looks healthy and he “feels good” about things. While that is not yet an official word from the bank, my friend breathed a sigh of relief, with hopes that he will not have any problems with the bank extending him credit.

Other farmers may not be so fortunate. There is a real possibility that this crisis will spell the end of some coffee farms that have supported entire families for generations.

View from the cupping lab terrace at Beneficio Las Segovias in Ocotal, Nicaragua. In the foreground is the new shade canopy Luis Alberto Balladarez has built to cover his triple-tiered raised drying beds as well as drying tarps for select coffees and experimental lots. Photo by Carabello Coffee.

A Letter to the President

Last month, a delegation from ANCN met with the government to discuss the letter they had sent to President Daniel Ortega. They delivered the dire news that this year’s harvest is 50 percent or less for the majority of Nicaraguan coffee farmers. They have asked for swift financial help to avoid what could be insurmountable losses for many farmers.

In truth, no one I spoke to harbors much hope for adequate government intervention. Yet, they continue to press for it.

Testing the Truth of Relationships

We have been sourcing coffee from these producers since 2012. During that time, we have always made conversations about pricing a part of the relationship, allowing the producers to share their cost of production with us, and to be a part of establishing a good price for the quality of what we are buying.

In addition to detaching price from the C Market, we also developed our own pricing tiers for large lots, micro lots and nano lots, since the smaller and more unique the lot, the higher the cost of production. With the cost of production up significantly this year, we believe this crisis represents the first true test of our financial commitments to this model of sourcing with these farmers.

Justin Carabello (right) with Jamir Garcia, who is relatively new to coffee. Presently he is studying agronomy at the university, while running two farms. Photo by Carabello Coffee.

While I’m not completely sure how to navigate this challenge, I have begun looking for ways to help by sharing what I have learned with our importer, my staff and some of our larger wholesale customers. More than anything, I have begun asking a lot of questions.

Can we adjust our pricing? If so, by how much? Are there creative ways we can help offset the high cost of production that will genuinely help these farmers without raising the per-pound price of the coffee this year? If my prices do rise, how much of that increase will our wholesale and retail partners be willing to share? And how do I effectively share all this information with them?

Or, should I see this as the nature of the agricultural world, where harvest yields historically rise and fall? Two years ago, when the harvest in Nicaragua was significantly higher than most years for my producers, I did not pay less for my coffee. Should I pay more now, especially considering I may not be able to increase my prices to my wholesale partners?

Situated between Mozonte and Jalapa, Finca Buena Vista is the first farm of Jamir Garcia, son-in-law of Luis Alberto Balladarez. Photo by Carabello Coffee.

So far I do not have the answers to these questions, and I accept that situations like these are incredibly complex and challenging. There are no easy answers, and what may be possible for one roaster may not be possible for another. But personally, I believe it is imperative that I wrestle with them and come to some conclusions if I want to tout these as relationship-based coffees.

My Request to You

If you are a roaster who maintains relationships with producers in Nicaragua, in humility and concern for these people, I respectfully urge you to:

- Reach out to your producers, and learn how they are being impacted by this developing crisis. If they have been impacted by this downturn, see if there is something you can do to help offset some of the losses they are experiencing.

- Contact your importer. They are a valuable asset in gaining insight and information in times like these, and will be able to help you contextualize these challenges. They will also be able to help you understand the best ways you can help your producers.

- Help us spread the word of this crisis to other roasters, and advocate that they act quickly to help ensure the short-term survival of many of these generational farms.

In the world of specialty coffee, we rightfully place a high value on connections at origin, using terms like “relationship,” “coffee partner” or “direct trade,” etc.

This crisis in Nicaragua is a hard test of these commitments, and we all have an opportunity to back up these words with meaningful actions, even if it might cost us all a bit more in the short-term to weather this storm.

Our group tours the Wet Mill at Finca Un Regalo de Dios, where they got to see coffee cherries being depulped and separated into fermentation tanks. Photo by Carabello Coffee.

Justin Carabello

Justin Carabello and his wife Emily started Carabello Coffee Company with a philanthropic vision, a hot air popcorn popper and eight pounds of coffee beans. Carabello's passion is leveraging people's love of coffee to help improve the lives of others in coffee-producing communities, specifically Nicaragua. The Carabello Coffee Roasting Works & Cafe are just across the river from Cincinnati, in Newport, KY.

Comment