[note: This article was co-written by Tom Johnson]

Once upon a time, in an unnamed city, an unnamed coffee company opened a new cafe. They had exotic tastes in espresso machines, and had purchased a beautiful, completely unheard-of model directly from a boutique European manufacturer. The crate was opened with care, the machine lifted onto the counter, and the whole staff gathered around to admire it.

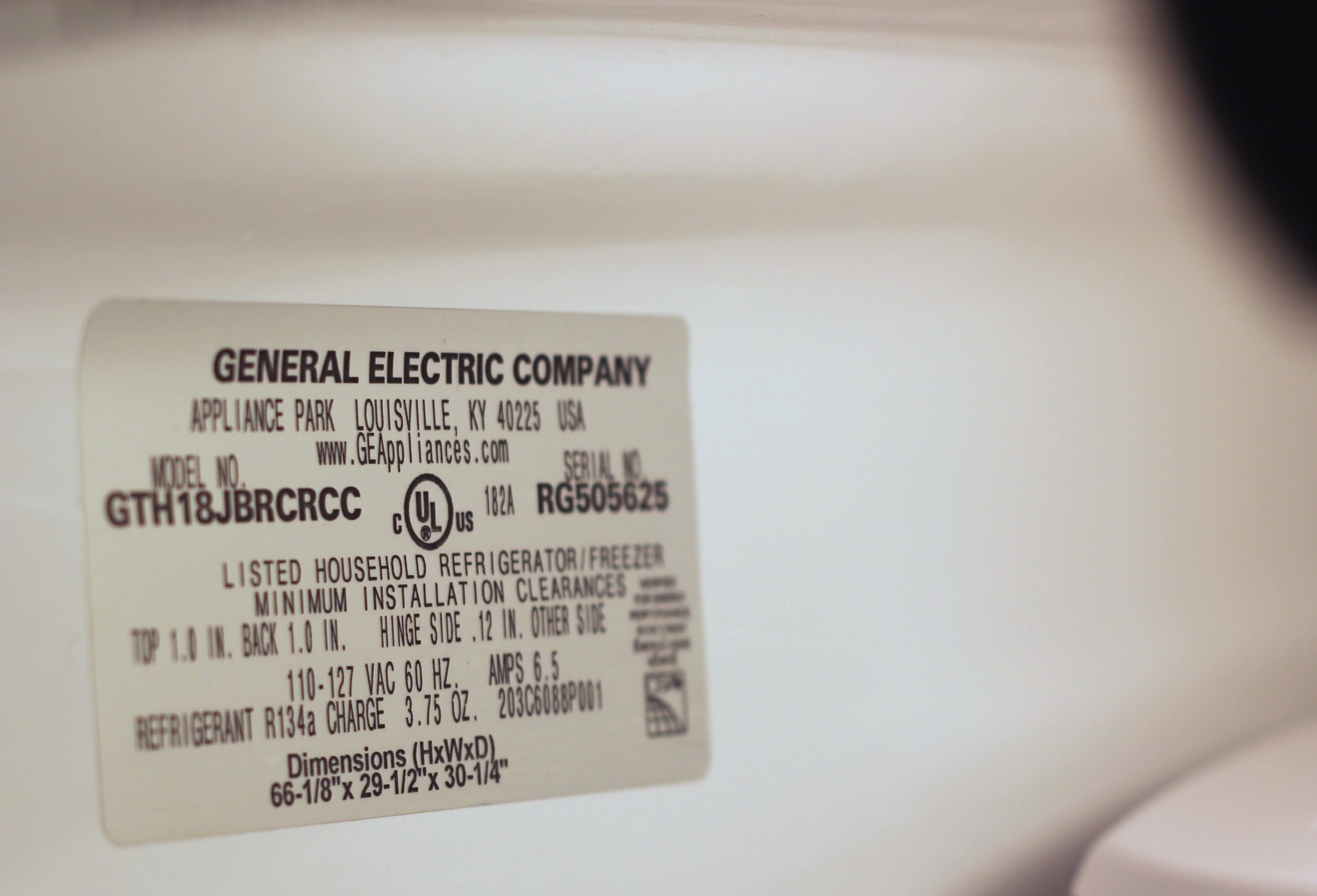

“Hey,” said a bright, young barista. “That machine doesn’t have a UL sticker on it.”

And in that angst-filled moment, the manager of the new cafe suddenly got very curious about UL. Could the machine be installed? Was it legal? Was it safe? And what, just exactly, was UL?

Underwriters’ Laboratory, or UL, was founded in 1894, as an organization devoted to safety. As the name infers, insurance industry underwriters needed a better way to evaluate relative electrical and overall safety of electrical systems and many other things since. They banded together to develop lab to conduct safety evaluation and develop safety standards.

Today, UL has two separate roles, one is that of a Standards Development Organization (SDO) for American National Standards Institute (ANSI), and the other is ANSI performance certification lab to which manufacturers can turn to have their products tested to applicable ANSI UL standardized test methods. Their first certified product was a tin-clad fire-proof door. Over the past 120 years, they have certified most of the major emergent consumer technologies in the United States, from blenders to e-bikes. They are currently a privately-held, for-profit LLC, having changed from a nonprofit in 2012.

This brings up an interesting corollary about what UL is not: It is not an “agency;” it does not pass laws; and it is not in any way part of the government. It does, however, carry a level of authority that one generally sees from government regulations. So, how does it work? The method here is the performance certification test “standard.” UL, and its counterpart for sanitation, the National Sanitation Foundation International (NSF), will research what it would take to make something safe, and the they’ll publish that as a standard that manufacturers can meet.

For instance, UL states that if you have a high-voltage electric heating element, you must have a thermal cutoff. That cutoff will stop delivering power to the element if temperatures get too hot. And that thermal cutoff switch cannot be part of the machine’s main brain, because it needs to work even if the brain is fried. This clause, and hundreds of others, are then collected into a standard. UL standard number 197, for instance, covers commercial cooking appliances, and includes espresso machines and coffee brewers.

If a manufacturer wants their product to be certified by a particular test standard, then they must meet every element of the standard and send their product in for inspection. You don’t have to use UL to inspect the UL standard, by the way; other agencies, like Intertek are ANSI accredited test labs and can also apply the ANSI UL performance certification test standard.

But why would anyone bother if UL doesn’t carry the weight of the law?

The answer is that many local governments, insurance companies, retail chains and other key stakeholders demand that any commercial appliance carry the UL sticker. UL itself may not have the power of law, but when statutory or administrative rules have normative references — meaning they are treated as a part of the code — to ANSI UL Standards, they might as well be law, as you cannot get an insurance policy on your shop unless all the appliances are “listed” and installed pursuant to the manufacturers’ instructions.

This still doesn’t mean that you’ll always find a sticker on every device in every cafe. Sometimes industrial equipment is inspected for safety by the local inspectors, as is often the case with cafe roasters. Some people are also just getting away with it, as not every local health inspector will even look for the UL or NSF mark.

Getting back to our intrepid cafe manager above: That machine can be installed, but you will want to first speak to your insurance company to be sure your coverage is not voided by installing an unlisted piece of equipment. If you get a rider and are covered, you may still get in hot water with one of the various inspectors who are going to have to sign off on the new cafe. The landlord’s insurance might want to have a say as well.

Finally, perhaps most importantly of all, the manager should care because the standards are there to protect the staff and the customers. They represent the best thinking in the world about how to protect the humans from their creations. As responsible members of our industry, we should always encourage safety in machine design and construction. Remember, your customers trust you, so if you are going to install something without the UL mark, make sure they know what that means. After all, you’re the one who will have to open the case and repair it someday.

[Editor’s note: This story is appearing as part of an unpaid editorial collaboration between DCN and the Coffee Technicians Guild. It was originally published in the CTG blog and is republished here with permission. The Coffee Technicians Guild (CTG) is an official trade guild of the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) dedicated to supporting the coffee industry through the development of professional technicians.]

Arno Holschuh

Arno Holschuh is the COO of Bellwether Coffee, which supplies production solutions for retail through their ventless, electric coffee roaster and innovative green coffee marketplace.

Comment

4 Comments

Comments are closed.

The concern I’ve heard raised over the years is the UL Rubber stamp. As the global consumer market has expanded, so has the scope of the ULs certification footprint.

They or their Contracted labs do not have the floor space to certify all of the millions of products that enter the market with the UL certs.

They don’t just certify Cooking equipment and Industrial transformers anymore and that is the underlining problem.

The big issue is their reliance on Industry Partners to do the right thing. Most concerning to me is the general cheapening of products which honestly is distressing because the biggest criticism of the UL system is they aren’t testing and inspecting products, but inspecting drawings and schematics NEW products. As well, if a company finds a cheaper option after the fact, nothing is stopping that company from making changes in say, China if the company feels it doesn’t interfere with the spirit of their cert compliance.

So the question is this. Is the UL now an Industry Partner or are they just as committed to their original mission as they were when founded? That is the Billion(s) of dollars question.

Good advice. After all, electricity and water do not play well. The last thing you need is an injured (or worse) employee or customer.

That said, there are (at least) two other agencies that regulate electrical product safety – the Canada Standards Association (CSA) and European Conformity (CE). Both are well-respected and are often acceptable as equivalent to UL in some areas. One should be aware, however, that many cheap imports will have a fake CE sticker affixed as nothing more than a marketing tool – you need to check the registration info carefully (the more expensive the appliance, the more attention you should give it).

In some areas it is possible to have a single unit locally (state/province/municipality) certified (especially if it meets one of the other certifications) for use after paying for an inspection. Many things differ between locations – such as the color of wiring and voltage and frequency demands, but those variations do not necessarily mean a product is unsafe. But always better to be safe than sorry.

I agree. I am not familiar with CSA, but in terms of safety, European CE standards are in many instances even more strict than our UL standards. Unfortunately, local government agencies and insurance companies have little knowledge of international standards, many don’t even know what CE stands for, or even understand the real meaning behind a UL label, and their ignorance often create unnecessary obstacles. Fake labels aside (I am pretty sure there must be many fake UL labels around as well) Legitimate CE certifications should be treated as UL certifications, and I believe it is time an official UL / CE equivalency be put in place. If local agencies begin to accept CE as an alternative to UL, hopefully insurance companies shall eventually follow

Safety and standards are all well and good. But the trouble with systems such as these certs is that its a one size fits all, and they also get caught up in the sheer volume of products coming to market. While the cert shows that it meets certain standards for “safety” (whatever THAT is defined as being in any given situation) there is NO standard set for quality that I know of. Some manufacturers get the UL/CSA/CE approval, but their stuff is junk, does not last, and can/does fail resulting in unsafe situations. I had a name brand burr grinder fry the motor and got so hot before I discovered it I thought it was going into full melt-down and fire. Had they used a motor costing perhaps ten cents more per unit, it would have been robust enough to have survived. If a motor fries before the brushes wear out, stopping it, it is a cheap motor. but UL and others never get into the long term use, common causes of failure, or fail-safe characteristics of appliances.

I should think a given manufacturer’s R & D process would serve well enough to produce a safe, reliable product perfectly suited for even commercial service. I’ve heard of health inspectors coming round to coffee shops and having fits because the Bodum french presses do not have the NSF sticker on them………. so what? Millions of them are in service worldwide and have been since 1926. I can also take an SNF certified tool and use it in such a way as to contaminate the served product.

Some of this is in the same category as fifteen airbags and backup video cameras being mandated in cars….. oh well. cost of doing business. Back in the late 19th century when UL first got started, yes there WAS a need for some sensibility in products being functional and safe. and UL stepped in and helped establish some needed standards. Then they made an industry of it, and even later, became a for-profit outfit. T