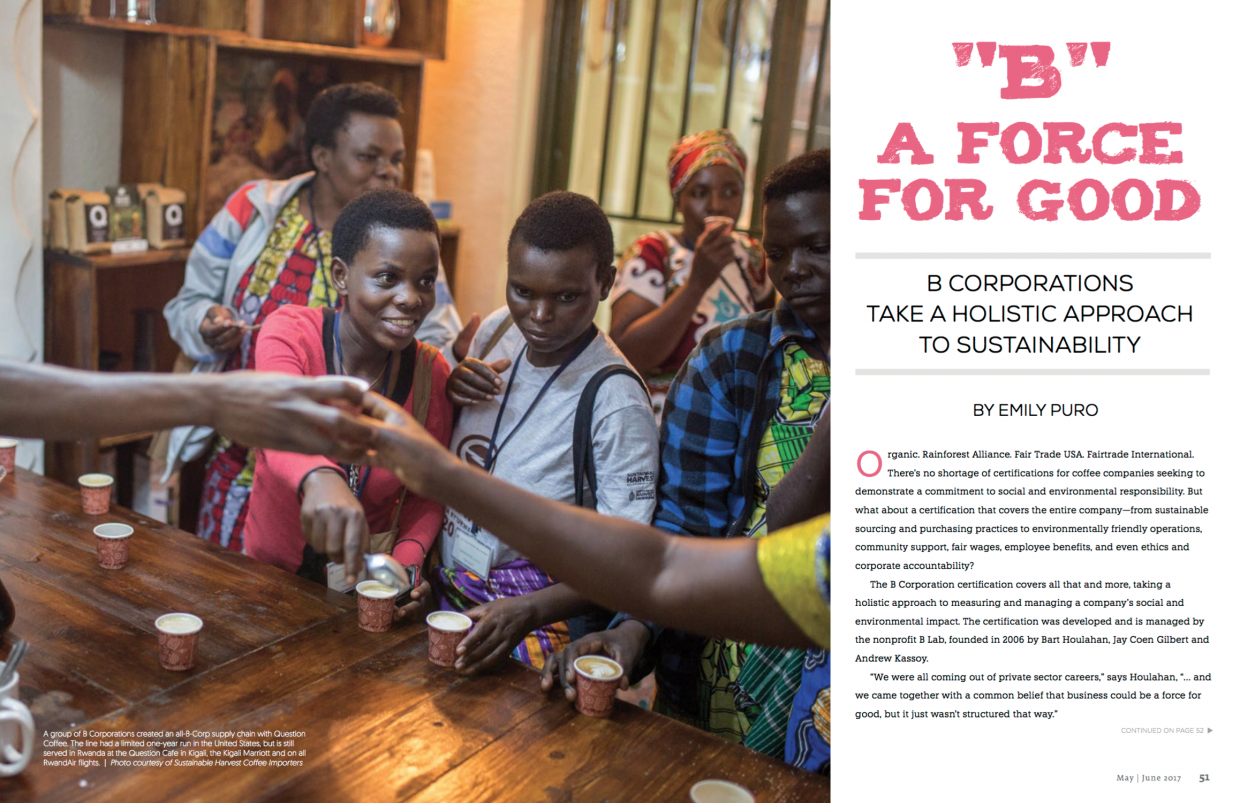

A group of B Corporations created an all-B-Corp supply chain with Question Coffee. The line had a limited one-year run in the United States, but is still served in Rwanda at the Question Cafe in Kigali, the Kigali Marriott and on all RwandAir flights. Photo courtesy of Sustainable Harvest Coffee Importers.

(Editor’s note: This article written by Emily Puro originally appeared in the May/June 2017 issue of Roast magazine.)

Organic. Rainforest Alliance. Fair Trade USA. Fairtrade International. There’s no shortage of certifications for coffee companies seeking to demonstrate a commitment to social and environmental responsibility. But what about a certification that covers the entire company — from sustainable sourcing and purchasing practices to environmentally friendly operations, community support, fair wages, employee benefits, and even ethics and corporate accountability?

The B Corporation certification covers all that and more, taking a holistic approach to measuring and managing a company’s social and environmental impact. The certification was developed and is managed by the nonprofit B Lab, founded in 2006 by Bart Houlahan, Jay Coen Gilbert and Andrew Kassoy.

“We were all coming out of private sector careers,” says Houlahan, “… and we came together with a common belief that business could be a force for good, but it just wasn’t structured that way.”

Coffee producer Gloria Rea with her parchment coffee drying in a covered and shaded raised bed patio at her farm in Ecuador. Photo courtesy of Caravela Coffee.

The “B”asics

The B Corp certification is not coffee-industry specific. There are more than 2,000 certified B Corporations in 50 countries across 130 industries, as of April 2017. Of those, only about 25 are coffee companies, including roasters, coffee shops, importers, exporters and others. A number of allied companies, such as Keep Cup in Australia and Bettr Barista Coffee Academy in Singapore, also are part of the B Corp community.

To become certified, a company must score at least 80 points out of 200 on the B Impact Assessment, which measures performance across four broad areas: governance, workers, community and environment. Each area is divided into subsections, such as corporate accountability, ethics and transparency under governance; compensation and wages, benefits, training and education, job flexibility/corporate culture, and health and safety under workers; job creation, civic engagement and giving, and suppliers and product under community; and so on.

The B Impact Assessment is developed by an independent standards advisory committee, which includes about two dozen academics, businesspeople, investors and other experts. It’s revised every two years, with numerous versions tailored to company size, location and primary industry. The assessment is free and confidential, and businesses can use it to measure their impact with no obligation to pursue certification.

After completing the initial assessment, a company seeking certification is required to submit supporting documentation to verify its claims; complete an assessment review; confidentially disclose any sensitive practices, fines or sanctions related to it or its partners; and complete a background check. About 10 percent of companies applying for certification are randomly selected for an in-depth site review, and recertification is required every two years. The annual certification fee ranges from $500 for a company with annual revenues of less than $150,000 to $50,000 for a company with annual revenues of more than $1 billion.

“I think a lot of companies in our industry are already acting in the spirit of, or with values that line up with B Corp,” says Jennifer Pawlik of Amavida Coffee. “They just might not be asking themselves the questions B Corp asks.” Photo courtesy of Amanda Coffee.

Considering the Big Picture

Many coffee companies that pursue B Corp certification already have a number of other certifications under their belts. Equator Coffees & Teas, based in San Rafael, California, for example, had organic and fair trade certifications and was certified as a green business by the Bay Area Green Business Program before pursuing B Corp certification in 2011. Why pursue another sustainability-focused certification?

“It’s different because this certification is holistic. It encompasses all of the business operations,” says Maureen McHugh, vice president at Equator. “If you’re talking about fair trade or organic, you’re really just talking about your product. With B Corp, it’s about every stakeholder in the business. It’s about employees. It’s about vendors. It’s about community relationships, where you physically are doing business and operate. It’s about taking responsibility for your impact. … It really speaks to the culture of the business.”

Another difference, says Jennifer Pawlik, program manager and benefit officer at Amavida Coffee in Panama City, Florida, is that the B Corp certification doesn’t dictate specific processes.

“Where a lot of certifications say, ‘You must be doing this,’ B Corp asks, ‘What are you doing?’” Pawlik notes. “The assessment is over 200 questions, and you mark the ones you’re doing. It paints a picture of who you are, and anywhere you didn’t check a box or have information to provide, it leaves this open space of opportunity for what you could be doing.”

Amavida Coffee’s social entrepreneur internship offers middle school, high school and college students the experience of seeing coffee production firsthand, while immersing them in local culture. Pictured: A visit to Chiapas, Mexico. Photo courtesy of Amanda Coffee.

Probably the most significant difference between the B Corp certification and others lies in the requirement to embed the principles of the program into the company’s articles of incorporation.

“It’s not enough just to demonstrate that you have the highest standards of social and environmental performance as indicated by the impact assessment,” says Houlahan. “We require all certified B Corporations to also change their governance so the mission of the business can withstand new money, new management, even new ownership.”

This can be accomplished in a number of ways, he explains, depending on where and how a company is incorporated. A limited liability corporation (LLC) or partnership based in the United States can simply rewrite its membership or partnership agreement, and B Lab can provide the appropriate language.

“If you’re a corporation, however, it depends entirely on where you are incorporated,” Houlahan continues. “In some states, you can rewrite your articles of incorporation and that will be upheld in a court of law, but in a significant number of states and in jurisdictions outside the United States, rewriting your articles won’t survive a challenge in court.”

As a result, the community of B Corporations advocated for the creation of a new legal entity, a “benefit corporation,” which is currently recognized in 30 states and Washington, D.C.

Benefit corporations commit to considering the impact of their decisions on all stakeholders — including employees, suppliers, the community and the environment — rather than focusing only on shareholder value. In addition, in most states where they are recognized, benefit corporations are required to produce a public report that details their social and environmental performance against a third-party standard each year. The B Impact Assessment is one of several recommended standards.

B Corporation Amavida Coffee has partnered with the Ohana Institute to host a social entrepreneur internship in which students envision socially and environmentally just coffee companies of their own. Photo courtesy of Amanda Coffee.

The Investment

In addition to the annual certification fee, becoming a certified B Corporation requires a significant investment of time.

“In terms of it being laborious and time-consuming, it’s all of that,” says Larry Larson of Larry’s Coffee in Raleigh, North Carolina, which certified as a B Corp in 2011. Larson’s team estimates the company’s most recent recertification took about a month to complete, with four or five individuals working on the sections relevant to their areas of expertise.

“It can be pretty invasive,” Larson adds, “a lot of deep questions, a lot of looking underneath the sheets sort of thing. Sometimes it feels like you get stripped down and you’re on parade.”

Pawlik notes that completing the questionnaire can feel more intrusive to a business owner than it might to another member of the team. She was an intern at Amavida during the company’s initial certification in 2014, and led the recertification process in 2016.

“It was probably a little easier for me, because I was just trying to get information and answer questions,” she says, “but for a business owner, it can be a pretty personal experience. The level of transparency is so new.”

Amavida Coffee runs a variety of fundraising campaigns to support its “Project Chiapas” program, bringing clean water to coffee-growing communities in Chiapas, Mexico. Photo courtesy of Amanda Coffee.

Coffee Enterprises in Vermont certified as a B Corp in 2013. In 2015, owner Dan Cox decided not to recertify, in part because the company had shifted its focus from producing products to providing consulting and quality testing services, but also because Cox found some of the assessment questions too intrusive. As an example, he cites one question asking if any employees live in low-income areas.

“I’m not about to ask my employees that,” he says. “It’s an invasion of privacy.”’

Questions about vendors were problematic, too. The company typically buys chemicals and lab supplies from large, national vendors, and Cox felt that obtaining details about those companies’ environmental and business practices as part of the assessment was excessive.

The process doesn’t get easier with recertification, Pawlik adds. During Amavida’s first assessment, for example, the company was composting and recycling, but didn’t have figures to quantify its efforts, so it merely “checked the box” for those activities. The company then began tracking its efforts, so during recertification it had figures for how much waste was recycled and composted, as well as documentation to support those figures, which meant more work was required to complete the assessment.

In addition, the assessment changes every two years, drilling down into more detail about each aspect of operations as developers become more adept at measuring corporate impact. With each version, “the bar gets a little higher,” says Houlahan, “encouraging continuous improvement.”

For companies familiar with other certification processes, completing the B Impact Assessment shouldn’t be too daunting, says Kelsey Marshall, co-founder of Grounds for Change in Poulsbo, Washington. His company roasts only fair trade- and organic-certified coffees, its coffee is certified carbon-free by carbonfund.org, and the company certified as a B Corp in 2010. But even for companies unfamiliar with certifications, he adds, “it’s not prohibitive.”

Larry’s Coffee installed nonreflective metal on the exterior of its “bean plant,” blocking heat from entering the building and reducing energy use in the summer. Photo courtesy of Larry’s Coffee.

The Return on Investment

Because awareness of the program is still relatively low, especially among consumers, it’s unlikely a company will see a significant increase in sales based solely on the certification. Still, certified companies can use B Lab’s branded labeling and other intellectual property, and some companies report gaining new business from other certified companies seeking like-minded partners.

“A lot of companies join us because they think this will help them attract new forms of capital,” says Houlahan, who notes that a number of socially responsible investment firms use the B Impact Assessment to rate potential ventures. Caravela Coffee, a vertically integrated green coffee company with operations in several Latin American countries, first came to B Corp because an investor requested it complete the Global Impact Investing Rating System (GIIRS), also based on the B Impact Assessment.

There may be additional financial incentives moving forward.

“In some jurisdictions we have found government trying to encourage more companies to either be a B Corp or be like a B Corp,” says Houlahan. “In some cases, that’s resulted in procurement preferences from government. In other cases, it’s resulted in modest tax benefits for B Corporations.”

Larry’s Coffee makes all its local deliveries in a biofuel-powered van. The company worked with a local fuel company to create the first biofuel pump in the county. Photo courtesy of Larry’s Coffee.

The Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) is a B Corporation and focuses on supporting socially responsible entrepreneurs. Mickey McLeod, CEO and co-founder of Salt Spring Coffee in British Columbia, is hopeful more financial institutions will follow suit.

“There’s no score on your balance sheet that says we invested X percent of value or X dollars toward making the world a better place,” says McLeod, whose company certified as a B Corp in 2010. “Usually, as a result you have less revenue because you’ve diverted some of that to doing things you think are going to, and do, make the world better. So I’m hopeful something like BDC is going to start to change that dial a bit, and other financial institutions are going to start to see this makes sense.”

Becoming a Better Company

Aside from any quantifiable impacts of B Corp certification, the most significant benefits appear to be internal, as companies use the assessment to improve their operations.

“Other certifications capture only one part of the supply chain,” says David Griswold, CEO of Sustainable Harvest Coffee Importers in Portland, Oregon, which certified as a B Corp in 2008. “B Corp means we’re looking at the whole thing. I really appreciate the way it makes us take a step back and think about everything.” The data tracking required to recertify every two years also makes the company more efficient, he adds.

“You learn so much about your own business as you go through the assessment,” says Adam Pesce, director of relationships for Reunion Island Coffee Roasters in Ontario, Canada. “There were things we did in practice that weren’t in policy, and those are great to enshrine in company policy so they’ll live beyond one person’s ideals and become practice for everybody, but there’s also so much you learn going through [the assessment] because it is a set of best practices.”

Seeing how Reunion Island compared to other companies — in coffee and in other industries — provided a roadmap for improvement. After certifying in 2013, the company implemented a green procurement policy, for example, requiring anyone purchasing supplies of any kind to research and evaluate sustainable solutions. The company also has focused on improving human resources policies.

“That was an area where we realized we were not doing as good of a job as we could, and we learned a lot from all of the things that were point-scoring on the B Corp assessment,” Pesce says. “I had a couple pages worth of notes at the end of it on things we could do for next time.”

After completing the assessment, many companies end up formalizing policies that have been practiced but not documented.

Chaff—the byproduct of coffee roasting—is rich in nutrients and can be used as bedding for household pets. Larry’s offers its chaff to the community for gardening or other uses free of charge. Photos courtesy of Larry’s Coffee.

“We may have had an informal policy about paternity leave, for example,” says McHugh, “but we didn’t have it in the handbook, so that’s not good enough. You have to write it down. You have to make it available for everyone. If you take the time to review, you discover it doesn’t take that much money or time to add [certain benefits], and it has a really positive impact on our employees.”

Similarly, Amavida was doing a lot of charitable giving when it first completed the assessment, but it didn’t have a policy in place. Now it does. Not only does that strengthen the company’s impact on the community, it cements the commitment into company practice.

“We find lots of companies join us when they’re about to raise capital, or have a succession event, a liquidity event,” says Houlahan, “and they want to make sure the mission that was so important to the company when they started it can survive bringing in new investors or an ownership transfer.”

The certification also can strengthen recruitment and retention efforts.

“Coffee professionals want to work for companies who are ambassadors for the specialty coffee industry,” says McHugh. “They want to be able to contribute in positive ways.”

Increasing one’s score with each certification — or even maintaining a high score knowing the assessment will become more difficult — provides strong motivation to continuously improve.

By helping producers in Nicaragua improve their farm practices—including raised bed drying—Caravela Coffee also has helped them increase their cup quality and raise the prices they earn by more than 60 percent over the past three years. Photo courtesy of Caravela Coffee.

“Scores goes up and down with each assessment, because they keep making it harder, which is challenging,” says Griswold. “If your score goes down, you’re thinking, ‘How do I get it back up?’ and you feel a healthy and happy competition to want to improve your score. That scoreboard is a key factor.”

“Once you have your score, the next year you want to get higher,” agrees Alejandro Cadena, CEO of Caravela Coffee, which certified as a B Corporation in 2014. The assessment shows where there’s room for improvement, he adds, “so it’s become a great target.”

While Caravela has scored remarkably high — more than 150 points on its initial assessment — it was not as strong as it could have been in the environment category.

“We didn’t do a lot of organic coffee, for example, so we decided to do more organic coffee and really support the farmers that we work with, and support more cooperatives and growers to become organic or get certified,” says Cadena. The company increased its organic offerings from less than 5 percent in 2014 to 12 percent in 2016. It also implemented recycling programs in all of its operations across Central and South America, and began measuring its carbon footprint with the goal of being carbon neutral by 2020.

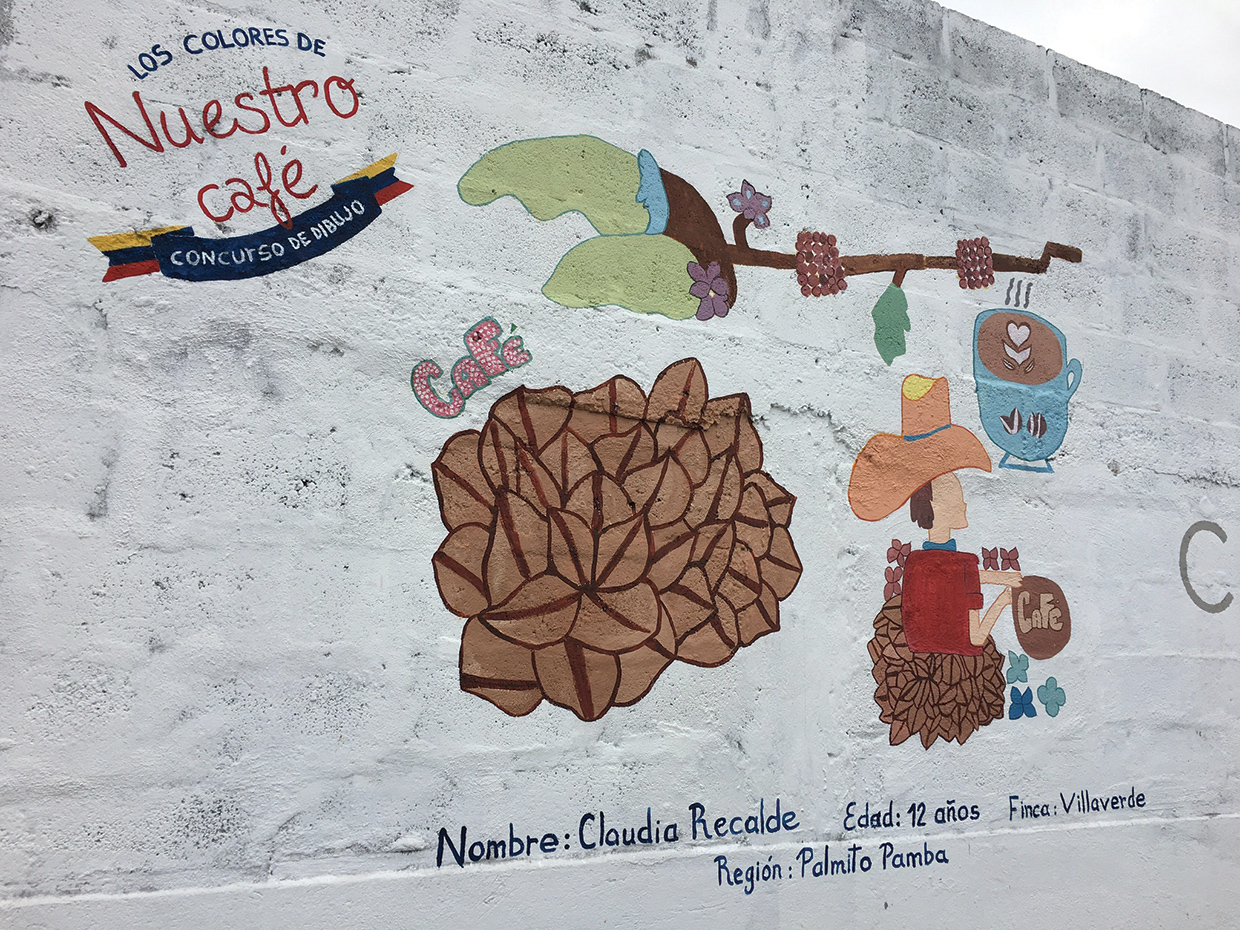

The winning drawing from Caravela Coffee’s “Los Colores de Nuestro Cafe” competition in Ecuador, painted outside the company’s dry mill in Quito. The drawing was submitted by Claudia Recalde, age 12. Photo courtesy of Caravela Coffee.

An Ongoing Education

Another benefit of joining the global B Corp community is gaining access to education about best practices across industries. Simply answering the questions on the assessment is a start, as the practices that garner the most points typically translate to the biggest impact. In addition, the B Corp community is set up to foster shared learning.

About 600 participants from B Corps around the world attended the annual “Champions Retreat” in Philadelphia in 2016, with the theme “What can we do together that we can’t do alone?” (The location and theme change annually.) Similarly, the B Leadership Development program organizes one-day meetings where leaders of certified B Corps come together to share knowledge and expertise. The program has been held in a handful of cities across the United States so far.

There’s also an online platform called the B Hive. When Pawlik posted questions about improving Amavida’s performance review process on a B Hive forum, she got a reply from King Arthur Flour detailing the 227-year-old company’s review process and sharing copies of its model. In addition, the person who responded said the company might be interested in purchasing coffee from a fellow B Corp.

“A few months later,” Pawlik says, “we found ourselves with a strengthened employee review process and working with King Arthur Flour to sell an office coffee program.”

Carlos Garcia, director of Caravela Coffee’s grower education program, gives a presentation for producers in Chalatenango, El Salvador, on improved coffee drying practices. Photo courtesy of Caravela Coffee.

Both McLeod and Griswold cite local B Corp meetings as a valuable cross-industry learning opportunity. Currently, B Lab is promoting an “inclusion challenge” in which certified companies commit to increasing inclusiveness in at least three areas of operation. The local groups have been a strong resource for sharing ideas and best practices.

“All of us are helping each other look at the metric that measures inclusion and equality in the workplace and pushing each other on how we can do better,” says McLeod.

Griswold is looking at how Sustainable Harvest can include employees in the company’s ownership. “I think the B Corp community is going to help me figure out that path over the next 12 to 18 months, in terms of how I start to structure something like that,” he says.

Of course, not every company finds the certification worthwhile. The annual fee was “more than it costs to join the SCA [Specialty Coffee Association] and some other organizations that we get a lot from,” says Cox, whose company did not recertify after selling its product development division to focus on quality testing and consulting services. “I’m not against the movement by any means, but for us … I didn’t see the value-added being realized.”

Mickey McLeod (right), founder and CEO of Salt Spring Coffee, with coffee farmer Byron Corrales at Sol and Cafe dry mill in Matagalpa, Nicaragua. Photo courtesy of Salt Spring Coffee.

Driving a New Economy

Certified B Corporations hope to lead a paradigm shift toward a new economy, one that measures success using a “triple bottom line” that includes social, environmental and financial impacts.

“We saw it as an opportunity to be a leader, not only in the coffee industry, but in business,” says McHugh.

As a tangible illustration of the viability of the B Corp model, a group of certified B Corporations created Question Coffee in late 2015. The grower (the Dukunde Kawa co-op in Rwanda), importer (Sustainable Harvest), roaster (Equator Coffees & Teas), transportation company (B-Line) and retailer (New Seasons Market) all were either certified B Corporations or had passed the assessment to become a B Corp. The line was produced as a limited one-year run in the United States, with all proceeds donated to the nonprofit Relationship Coffee Institute for investment in farmer training. Question Coffee is still sold in Rwanda, and is served at the Kigali Marriott and on all RwandAir flights.

“The question we were trying to pose with Question Coffee is, how do you get consumers to get behind a sustainable supply chain,” says Griswold, “because it really does come down to a crowded marketplace with complicated messages, and how does sustainability fit into that?”

Larson notes that for B Corporations to drive the economy forward, greater awareness of the program is essential.

“The more we have consumers looking at B Corp, looking deeper into what the heck B Corp is,” he says, “the better our chance of succeeding in this march toward sustainability as a society.”

Salt Spring Coffee founder Mickey McLeod (far right) with a group of coffee farmers at a micro-washing station in Uganda. Photo courtesy of Salt Spring Coffee.

The program does seem to be gaining visibility. B Lab has partnered with a number of municipalities on a “Best for” program that uses the assessment to rate and recognize local companies (“Best for New York,” for example). Awards are presented in “best overall,” “best for workers,” “best for the environment” and other categories.

In addition, the SCA used questions from the B Impact Assessment to vet roasters applying to have their coffees served at this 2017 Re:co symposium. Kim Elena Ionescu, the SCA’s chief sustainability officer, says she and other organizers — including Adam Pesce of Reunion Island and SCA’s brand strategy director Stephen Morrissey — used the assessment because they wanted to take a “holistic” approach to sustainability.

“Standards for farms and for how coffee is grown are useful,” says Ionescu, “but it can seem like the onus is on the farm or farmer, or that the only role of the roaster or retailer is to buy the right coffee.” Instead, she says, “we wanted to celebrate people who are buying coffee well, but also doing important work to be great businesses and a great model for other companies.”

In a marketplace where sustainability means different things to different people, and claims of eco-friendliness often go unverified, the B Corp certification can provide a scorecard to measure companies against a common metric.

“That’s good for coffee, too,” says Griswold, “because it creates sustainable companies instead of just a sustainable product.”

Emily Puro

Emily Puro is a freelance writer and editor living in Portland, Oregon. In addition to Roast, her articles and essays have appeared in Writer’s Digest, Better Homes and Gardens, Portland Monthly, Northwest Palate, The Oregonian and numerous other publications. She enjoys learning about the art and science of coffee, as well as the social and environmental impacts of the industry, and she continues to be amazed by the remarkable professionals throughout the supply chain devoting their lives to this work.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Well, that’s very useful post and inspiring too. Thanks for sharing.