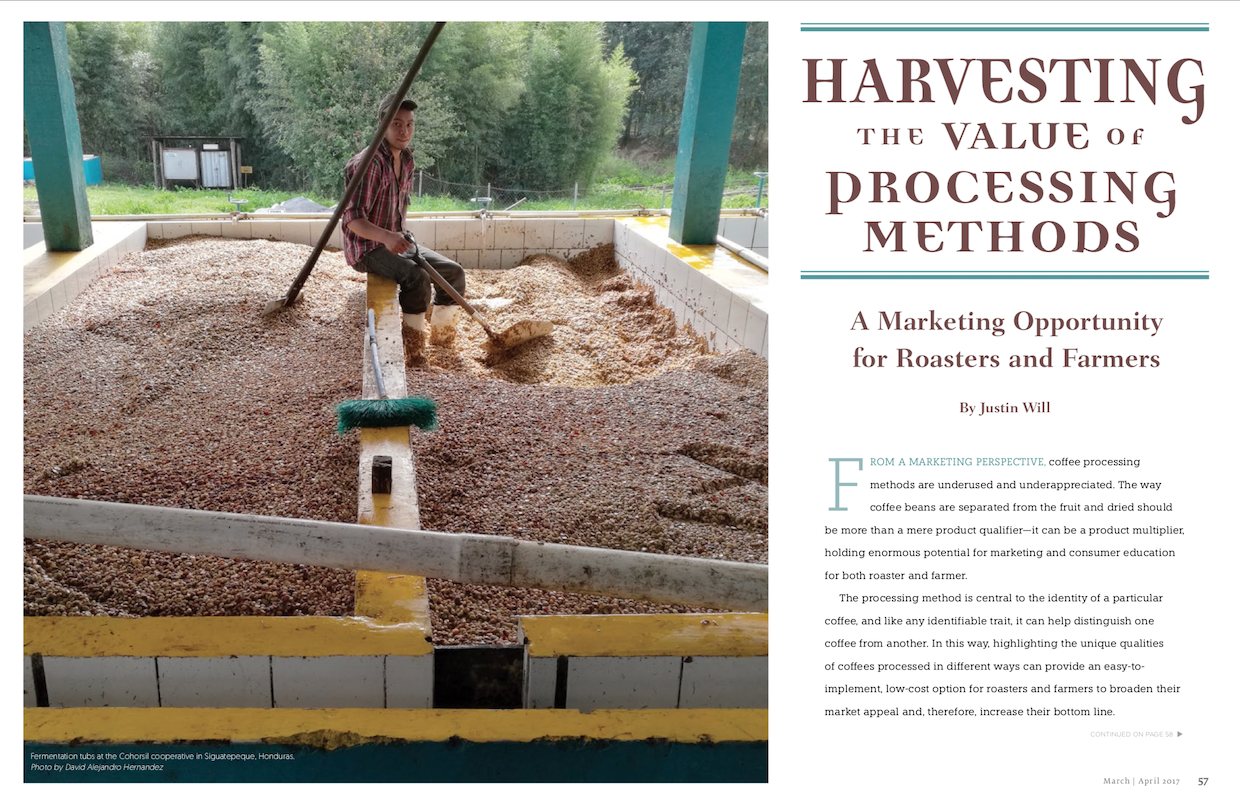

Fermentation tubs at the Cohorsil cooperative in Siguatepeque, Honduras. Photo by David Alejandro Hernandez

(Editor’s note: This article written by Justin Will originally appeared in the March/April 2017 issue of Roast magazine.)

From a marketing perspective, coffee processing methods are underused and underappreciated. The way coffee beans are separated from the fruit and dried should be more than a mere product qualifier — it can be a product multiplier, holding enormous potential for marketing and consumer education for both roaster and farmer.

The processing method is central to the identity of a particular coffee, and like any identifiable trait, it can help distinguish one coffee from another. In this way, highlighting the unique qualities of coffees processed in different ways can provide an easy-to- implement, low-cost option for roasters and farmers to broaden their market appeal and, therefore, increase their bottom line.

Differentiation by Processing Method

Processing methods typically fall into two broad categories: wet process, which includes fully washed, semi-washed, and pulped natural (also known as honey); and dry process, also known as natural. This refers to the differences in how the cherry is processed, the goal of which is to obtain a dry, ready-to-export, green coffee bean. (See the “Coffee Processing Terms Are Evolving” graphic below for information about new terminology developed by the Specialty Coffee Association.)

With natural processing, for example, the bean is dried while still inside the cherry. In the fully washed and semi-washed methods, the skin, pulp and mucilage are removed before drying, either through biological fermentation (fully washed) or by machine (semi-washed). In the pulped natural or honey processing method, the skin is removed before drying, but some or all of the pulp/mucilage is left on the bean during drying.

These differences have an impact on the flavor in the cup. It’s impossible to predict the exact effect each processing method will have on the flavor profile, as there are numerous other variables at play, including origin, variety, soil conditions, climate and elevation. However, in an informal poll of 24 coffee experts — including farmers, traders, importers, exporters, roasters, cuppers, baristas and consumers from 11 different countries — all agreed that processing methods affect coffee flavor. Many of those surveyed specifically noted effects related to sweetness, body, acidity, fruitiness, clarity and complexity.

Whatever the particular effect, this capacity for processing methods to differentiate coffees within a single lot can be a useful marketing opportunity for roasters and farmers alike.

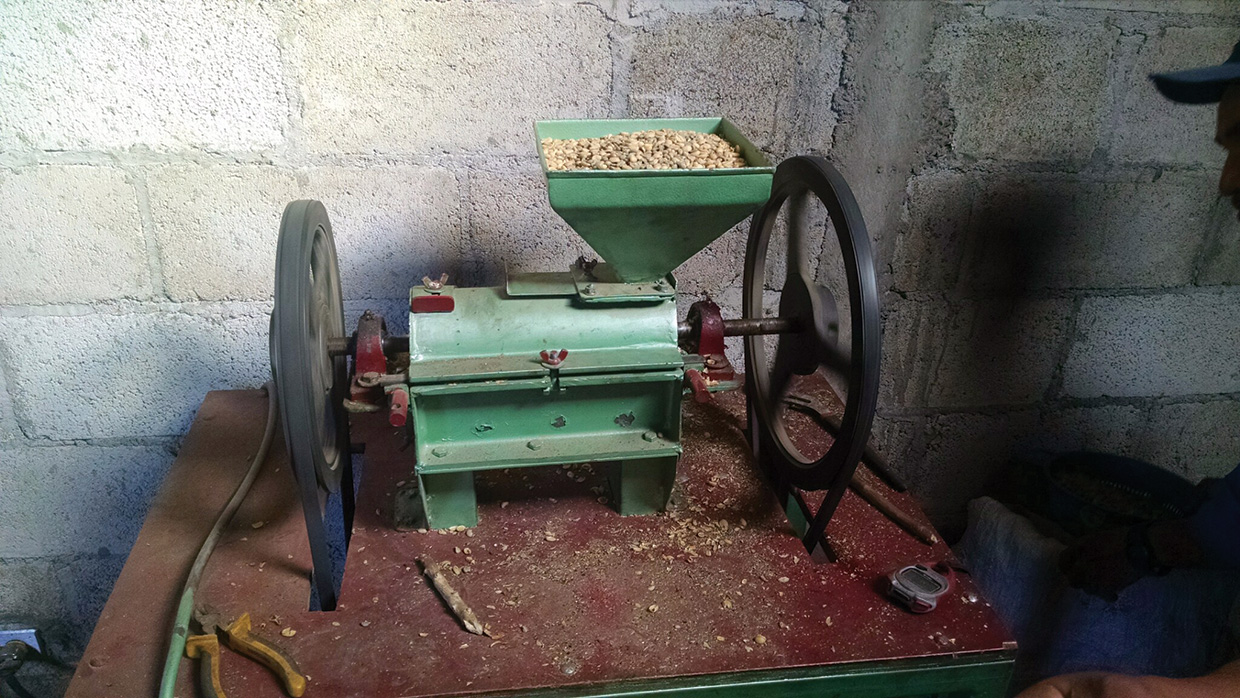

A parchment milling machine removes parchment from dried green coffee before exporting and roasting. Photo by Justin Will.

The Farmer’s Perspective

Coffee processing often is dictated by the availability of resources — especially water — and/or local tradition. Certainly, market demand plays a part as well, so it’s important for roasters, retailers, and possibly even consumers to understand why a farmer selects one process over another. To glean more information about this, I held detailed conversations, in person and by email, with 10 coffee farmers from Peru, Colombia, Nicaragua, Panama, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, India and Brazil.

This is what I learned: The specialty coffee farmer with purely economic interests is likely to focus exclusively on washed coffees, because those have the highest potential for sale to the market-at-large and the most predictable results. The farmer who’s looking for a higher selling price may have a higher threshold for risk and more to gain from using alternative methods, so he or she will experiment with other processes to diversify. The risks are significant, however, and a farmer whose entire income depends on coffee production is unlikely to risk that income on experimental methods.

“This decision really depends on the economic goal of the farmer,” says Roger Roland, founder of Tierra Cafetera — which operates farm management, milling, exporting and other origin-based services — describing the situation in Colombia. “If they are trying to produce as much coffee as possible as quickly as possible, then washed is the way to go. A farmer selling into the specialty market, however, wants to present the best cup for each coffee in order to capture the best price. In this case, other methods such as natural or honeyed become more interesting, even though they are typically riskier and are much harder to manage at the farm.”

Climate also plays a huge role in this decision. The purpose of drying coffee is to reduce the moisture content of the bean, and because both honey and natural processes have more moisture to remove — as the skin, pulp and/or mucilage is still attached during drying — these require more drying time. This makes honey and natural methods less compatible with wet and unpredictable climates. A hot, dry climate (such as Ethiopia) lends itself to natural processing, while a hot, wet climate (such as Peru) lends itself to washed, which still requires significant drying time, but less than other methods. Additionally, machines such as mechanical dryers may change this equation, but they are expensive to purchase and operate.

In light of this, processing method diversification could become a useful tool for farmers to mitigate the impacts of climate change on coffee production.

The effects of climate change on the availability of water also impacts the choice of processing method, as the pulpers used for the washed method historically have required a great deal of water to operate. This is changing, as more efficient machines are being developed that operate with less water, but these machines can be prohibitively expensive.

Lastly, farmers often stick to what they know. Edith Meza Sagarvinaga of Finca Tasta in Peru recognizes this, and makes a deliberate effort to innovate and diversify when she can.

“The producers are free to do the process they want [in Peru], but they only do washing because that’s what they learned,” she says. “Natural and honey processing are more time consuming, but we try to do them whenever the weather is good. We do a lot of experimenting on our farm.”

At Finca Tasta, located in the Llaylla district of Satipo, Peru, farmer Edith Meza Sagarvinaga experiments with different processing methods to diversify the coffees she can offer to buyers. Photo by Edith Meza Sagarvinaga.

The Consumer Market

While choosing a processing method is critical for the farmer, the apparent importance diminishes as you move down the supply chain. Once the coffee has reached consumer countries, the processing method is only listed, if at all, with other attributes such as altitude, origin and variety. In many cases, once the coffee is roasted, the packaging won’t list any of these features. This, of course, has changed with the increasing market for specialty coffee, but there is no standard for the industry, and many roasters believe there isn’t a sufficient level of consumer education to make the additional labeling worthwhile.

In a study of 40 roasters in London, San Francisco, Chicago and Boston, I found 90 percent of the roasters surveyed in London and 70 percent of those surveyed in San Francisco include the processing method on their labels, compared with only 50 percent in Chicago and Boston. These market differences might illustrate a disparity in consumer education, or at least consumer expectations.

For a better understanding of this phenomenon, I questioned the 24 coffee experts mentioned previously, and I observed a lack of faith in the awareness of the consumer. When asked to rate their impression of consumer knowledge on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the most knowledgeable, the average response was 2. Even more surprising was the divergence of opinions between producer-side and consumer-side experts. Farmers and exporters generally believed that processing methods were more important and better understood than their consumer-side counterparts.

All of this indicates that, while roasters may appreciate the diverse flavor profiles resulting from different processing methods, and farmers may recognize the economic realities of selecting different processing methods, the case made to the consumer is still staggeringly underwhelming. What the consumer needs most in this education campaign is a comparison tool.

Enter the Coffee Processing Product Series

A “product series” is a marketing technique that allows consumers to evaluate a specific product attribute by placing two similar products side by side. In the case of coffee processing methods, the series would include two or more coffees of the same variety, from the same farm and lot, processed in different ways. In this way, the featured attribute — processing method — can be isolated for a focused comparison.

While some roasters and retailers are using this type of comparison set, I believe it has been woefully underused. In my survey of 40 roasters, only two offered a set with more than one coffee from the same farm processed in different ways. One of those roasters is River City Roasters, located just outside Chicago.

(Note: Since the original publication of this article, River City Roasters changed its name to Five & Hoek Coffee Co.)

“We are a small-batch roaster, and while we source some of our coffee through the typical importers, we are most proud of the direct relationships we’ve established in Africa,” says Tyler Fivecoat, one of River City’s owners. “Our partner in Burundi, Long Miles Coffee Project, has been very collaborative and supportive of what we’re doing. We started off with their natural-processed coffee last year, and added the honey this year. We like to sell them side by side as a series so customers can compare the two methods directly.”

The nuances of coffee attributes can be subtle, much like anything that requires a trained palate to detect, so the differences can be hard to notice without placing them side by side.

Kona, Hawaii’s Carta Coffee offers a rotating side-by-side sample set. The first set included the same coffee, grown on the company’s farm, processed in two ways: natural and washed. Photo courtesy of Carta Coffee.

The Business Case for Comparison Coffee Sets

The specialty coffee market has become a niche of artisan consumption that rewards business owners who meet higher standards by paying them higher prices — but that doesn’t mean the needs of that specialty market are easily satisfied. The demand is mercurial and trendy, and companies must always be innovative. It’s hard to keep up, even for those who devote their lives to it. New roasters and coffee shop owners struggle with this, especially when it comes to where to source their beans and how many different coffees to offer. The more coffees offered by the shop, the more complex the logistics can become.

“The specialty coffee market is demanding, and cafes and roasters need to be able to offer unique options, appealing to the taste and cost preferences of customers,” says Ben Tanen, roasting director for Brewpoint Coffee in Elmhurst, Illinois. “For coffee, this can mean sourcing from four, five, or even more different origins.”

While this may be managed by purchasing coffee through a single importer, it’s almost impossible to manage via direct trade. Seasonal offerings add even more complexity.

In this light, the idea of differentiating coffees by processing method — using a special comparison series to showcase the differences — makes logical as well as logistical sense. When a roaster can source multiple products from a single farm, it can reduce the total number of farms from which it sources, simplifying the logistics while still expanding product depth.

Benefits for the Farmer

The farmer also can benefit from this expansion, as it directly correlates to the marketability of the product line. Variety is leverage in the specialty coffee market.

“The importance of producers diversifying their processing methods is that it allows them to not only differentiate their coffee from the rest, but generate an extra income for the same core product,” says Carlos Umanzor, a coffee trader with Volcafe Group in Honduras. “At the same time, it puts them in a better bargaining position with buyers in local and external markets. I will add, though, despite diversifying the process, consistency in the cup remains crucial to see positive results.”

Changing or adding processing methods to an operating farm isn’t always as difficult as one might think. In the case of farms accustomed to natural coffees, a large investment would be required to upgrade equipment for washed coffees, but it is likely to be profitable once implemented because it will be easier to manage quality. On the other hand, transitioning from washed to natural- or honey-processed coffee can be tested on a small scale with no upfront costs. Several farmers I spoke with first experimented with various honey and natural processing methods on a small batch of cherries (approximately 5 kilograms). After identifying a successful process, these farmers began experimenting with a larger share of the harvest. This is where the risk to the farmer comes into play because, as mentioned earlier, naturals and honeys can be harder to manage and are more labor intensive than washed coffees.

There is also the element of scarcity. In the case of Panama, which uses the washed process for 95 percent of its coffee, the potential benefit for experimenting with other methods is huge. Even if the climate isn’t ideal for naturals because of frequent rain, smaller lots can be processed using those methods when the weather clears, as Sagarvinaga has been doing in the similarly wet conditions of Peru.

“In Peru, the market for washed coffee is saturated,” she says. “To offer something else is extremely beneficial in finding the best price, especially when exporting, because foreign buyers love to try new things. It’s how we differentiate ourselves, at least among Peruvian farmers that only offer washed coffees. This year, roughly a third of our coffee will be natural, and 20 percent honey, as long as the weather cooperates.”

TOP: Coffee beans showing varying degrees of honey processing—black, red, yellow and white—as well as a washed coffee. BOTTOM: Three stages of yellow honey coffee: parchment, washed and roasted. Photos by Edith Meza Sagarvinaga.

What’s Next?

As the coffee industry continues to globalize and expand the channels of communication throughout the supply chain, product differentiators will become more essential to the marketability of specialty coffees. It is striking to note that only eight of the 40 roasters surveyed in London, San Francisco, Chicago and Boston used processing method as a defining characteristic of their coffees, meaning the processing method was used in the product title or featured prominently in descriptions online.

Even if one assumes that washed coffees generally go unmarked because they are considered the standard, including the processing method on coffee packaging could be the first step in educating consumers. Given the significant impact of processing methods on cup profiles, I would argue that processing method should be featured as visibly as origin. Roasters can drive consumer education in this area by increasing the significance of the processing method on labeling, and by offering consumers accessible ways to explore the differences.

During the year or so that River City has been offering its processing series, Fivecoat has received positive feedback from customers.

“Processing methods have been a new concept for a lot of our customers,” he says, “so the series offers the perfect outlet for them to better understand their beverage.”

- Wet milling at the Cohorsil co-op in Honduras. Photo by David Alejandro Hernandez.

- Sorting at the Cohorsil co-op in Honduras. Photo by David Alejandro Hernandez.

- Patio drying washed coffee at the Cocabel cooperative in Belen, Lempira, Honduras. Photo by David Alejandro Hernandez.

And while offering consumers an opportunity to taste the differences at home can be a powerful educational tool, hosting tasting events can offer an even better educational experience. Not only do they ensure the consumer will taste the coffees side by side and brewed to the same specifications, events allow the coffee professional to guide the experience, answer questions and foster a deeper dialogue about processing methods. Many roasters already host public cuppings and educational events; why not design an event to showcase the distinctions between processing methods?

“There is a huge opportunity there,” says Fivecoat.

Still, none of this can happen without more farmers offering coffees processed in diverse ways — when it is financially feasible for them to do so. A professional farmer with stable production and diversified sources of income is an ideal candidate for experimentation. Roasters can do their part to increase demand for diverse processing methods — and thus lessen the risk for farmers who are willing and able to experiment — by highlighting the processing methods and educating consumers about their effects in the cup.

Processing methods have long been a response to environment and history, but moving forward, they can represent financial boons for smallholder farmers, marketing opportunities for artisan roasters, and engaging educational experiences for curious consumers.

Justin Will

Justin Will holds a master’s degree in coffee economics and science from the Università degli Studi di Trieste in Italy. He runs a coffee import and consultancy business, JWC Coffee Merchants, based in Chicago. Learn more at inspiredcoffee.com.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

I have had the opportunity to have in store two lots of the same day’s pick from the exact same coffee, harvest was so abundant that the day’s pick brought the wet process side to capacity, so the remaining coffee coming off the fields (about a quarter of the day’s pick) was simply laid out on the drying patios in cherry. Both coffees are astoundingly good. The washed portion of the day’s pick was entered, and placed well in the Cup of Excellence that year. Personally I thought the full natural part of the harvest was a better coffee. The fruit and sweetness of the natural was more pronounced, and it had the acidity to balance well. Much heavier body, which I prefer. They need to be roasted rather differently to bring out the full potential of each, but that was just part of the fun. T