Nearly a year ago, as the current coffee price crisis was becoming painfully apparent to the industry at large, Daily Coffee News published “A New World Coffee Order.” Written by Luis, the article called for different coffee value chain players to rethink their roles on how they can develop and better distribute value.

Luis insisted that generating and sharing value in the coffee industry should not be a zero-sum gain of winners and losers — as many voices from the producing world seem to currently characterize it — and that well-thought-out partnerships, already frequent in the third wave coffee movement between individual farmers and key roaster players, have demonstrated an ability to create value and unlock opportunities for different value chain participants, including of course farmers.

In this two-part article, we will suggest possible ways to achieve a more balanced relationship between coffee buyers — whose responsibilities for procuring coffee are evolving — and farmers or origins who are willing to engage in longer term and continuous improvement processes that focus on knowledge, quality and transparency.

We also lay out pathways that could help forge longer term relationships between origins and brands at a larger scale, shifting from market-driven value chain governance to a relational governance that improves the producers’ abilities to capture additional value.

But first…

A Historical Perspective of the Procurement Responsibilities

For many years, commodity procurement professionals in most industries had three major responsibilities:

- to ensure that raw materials will arrive on time to their facilities so that the plant does not suffer an interruption in production and delivery of the final product to distribution outlets. It was judged that the worst risk a company could face was that of lost sales to competitors in grocery chain aisles due to lack of product availability, which leads to the trial of other brands by consumers and eventually loss of long term loyalty.

- The second major duty was to optimize prices and qualities, reducing the average cost of the blended raw material to ensure competitive final product pricing.

- The third important task was to buy or hedge the prices at which the commodity was bought within a reasonable range of the market average. In the coffee category, this meant the average of C market prices for mild Arabicas or LIFFE for Robustas, and the average differentials or premiums for certain qualities from different origins. Those buyers who complied with the first two responsibilities and were able to close the year with numbers significantly lower than the market average would be given bonuses and rewards.

In the competitive and undifferentiated coffee category of the 1980s and ’90s, a procurement offices performance was a key factor for the company and brand results. Consequently, head procurement officers had significant power both within their companies and before their vendors. Names like Paul Keating and Dave Brown (Maxwell House), or Greg White (Folgers) in the United States, or Jürgen Gotchalk (Tchibo) and the different heads of Taloca and Decotrade in Switzerland defined an era where efficient and competitive coffee procurement had a highly significant influence on a coffee roaster’s profitability.

These responsibilities, and the rewards involved, contributed to the industry’s “race to the bottom,” building continuous downward pressure to reduce costs and prices, and keeping the coffee buyer at the center of the business. In many cases, the end result favored the production of lower-quality blends that could compete with very competitive grocery store brands, often used as “loss leaders” to attract traffic to the stores. Needless to say, during these decades, consumers were less than enthusiastic within the coffee category, which was nearly stagnant in North America, and even contracted in Germany, one of the biggest markets in the world.

The lack of differentiation and the coffee price crisis at the turn of the century, which saw mild Arabica C market quotations of nearly 40 cents per pound, helped fuel the specialty coffee industry, providing ample space for new brands that could develop a quality reputation at reasonable green coffee prices. New brands with more sophisticated value propositions around espresso-based beverages catered to more sophisticated consumer tastes, creating segmentation opportunities for new coffee brands.

Additionally, the media headlines highlighting the extremely difficult conditions in coffee growing countries, compounded with the frequent sweatshop scandals faced by apparel brands, helped pave the way for Oxfam, the Fair Trade movement and other NGOs to start focusing on the coffee value chain. Sustainability seals, which started in the specialty industry, promptly made headway into mainstream or conventional brands, forcing procurement professionals, importers and even exporters to better understand where and how their beans were grown. With time, environmental concerns also grew, enlarging the agenda of certifying agencies.

For many brands, the interest or need to better understand the different value chains and coffee origins became an additional opportunity for differentiation. Thus, specialized importers and adventurous coffee buyers started to travel to origin communities, identifying and buying unique green coffees to second wave brands. Under this model, the buyers not only performed the traditional roles of procurement, but also became the sources of unique narratives based on coffee knowledge and their travel experiences. These were adopted by their marketing colleagues to support the sale of higher-quality and higher-priced coffees.

However, many conventional brands found it convenient to “outsource their sustainability policies” to third-party voluntary sustainability standards (VSS), which to a certain extent, implied continuing with the “business as usual” model. Thus, the VSS model became more popular with larger brands, generating more revenue for the seals, but at the same time became less relevant for the most differentiated brands that required more tailored narratives to justify their higher prices.

As a result, a large portion of the coffee industry volume — and the dynamics of commodities procurement — did not change. All in all, the jury is still out as to whether there is a positive overall impact for the sustainability seals, particularly in terms of economic sustainability. This issue is highlighted in a discussion with Xiomara Quiñonez in the article “Towards a Balanced Sustainability Vision for the Coffee Industry.”

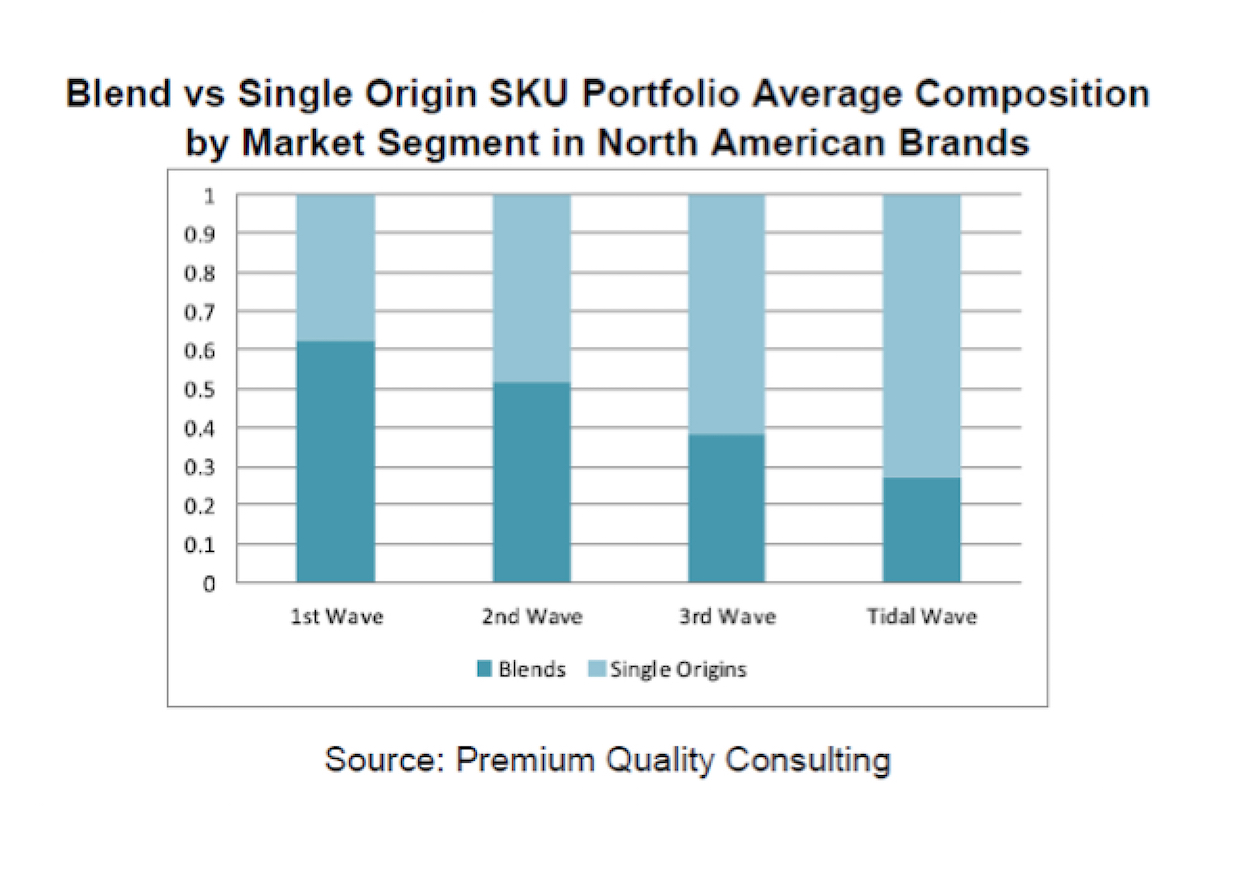

However, the ability to complement brand differentiation with origin narratives has become a positive trend across different market segments. The third wave coffee movement has demonstrated that single-origins are key to coffee industry growth and brand success. They are capable of bringing emotions and authenticity to coffee offerings, and are a key complement to the artisanal offerings that are part of a curated coffee drinking experience. To be relevant, specialized, and knowledgeable, other brands have increased the presence of single-origin coffees — largely defined as sourced from a specific farm, community, region, or country — across their product portfolio (see graph).

Revisiting the Indiana Jones Model

Despite these positive developments in many coffee markets of the world, most farmers and origins continue to be interchangeable, reducing the ability of producers to achieve a better negotiation stance with exporters and brands. As pointed out with Daniele Giovannucci and Luciana Marques Vieira in The powerful role of intangibles in the coffee value chain, this state of affairs leads to an extremely unequal distribution of value between producers and buyers. The academic literature on value chains would argue that most of the green coffee transactions take place under a hierarchical, or market-driven value chain governance, limiting the economic upgrade opportunities for producers.

This is the case even with many brands identifying with the third wave coffee segment — brands that knowingly or not promote the notion to consumers that the industry hero is the coffee buyer. The buyer in these settings is portrayed as a unique individual who has the knowledge and expertise to find “coffee gems” in exotic places and bring them to the market for recognition.

Coffee buyers communicate their work in a variety of forms, ranging from “origin newsletters” issued by specialized exporters and importers focused on farmers and their communities, to videos and Instagram pictures documenting coffee travels. While these are positive efforts, they also clearly show that communicating origin stories is still in the hands of buyers, intermediaries or VSS agencies, and that the focus of these stories is not the specific origins.

This “Indiana Jones” model uses a storytelling framework that communicates both coffee knowledge and emotions, creating more interest in single-origin coffees. In these cases, the storyteller and the credibility belongs to the brand, leaving farmers and origin intangibles in a diminished role, which means that provenance continues to be, to a certain extent, interchangeable. In this hierarchical value chain governance, the costs for the coffee farmer to switch buyers are higher than for the coffee buyer to switch origins. Clearly, in these cases, brands continue to see origins and certified products as “sources,” rather than partners.

One industry objective should be to create the conditions for a growing portion of producers and buyers to work under a different framework: a relational governance. Under this model, present in certain third wave coffee value chains, both farmers and buyers depend on each other’s performance, generating the incentives to cooperate and create additional value. They are both heroes of the origin story.

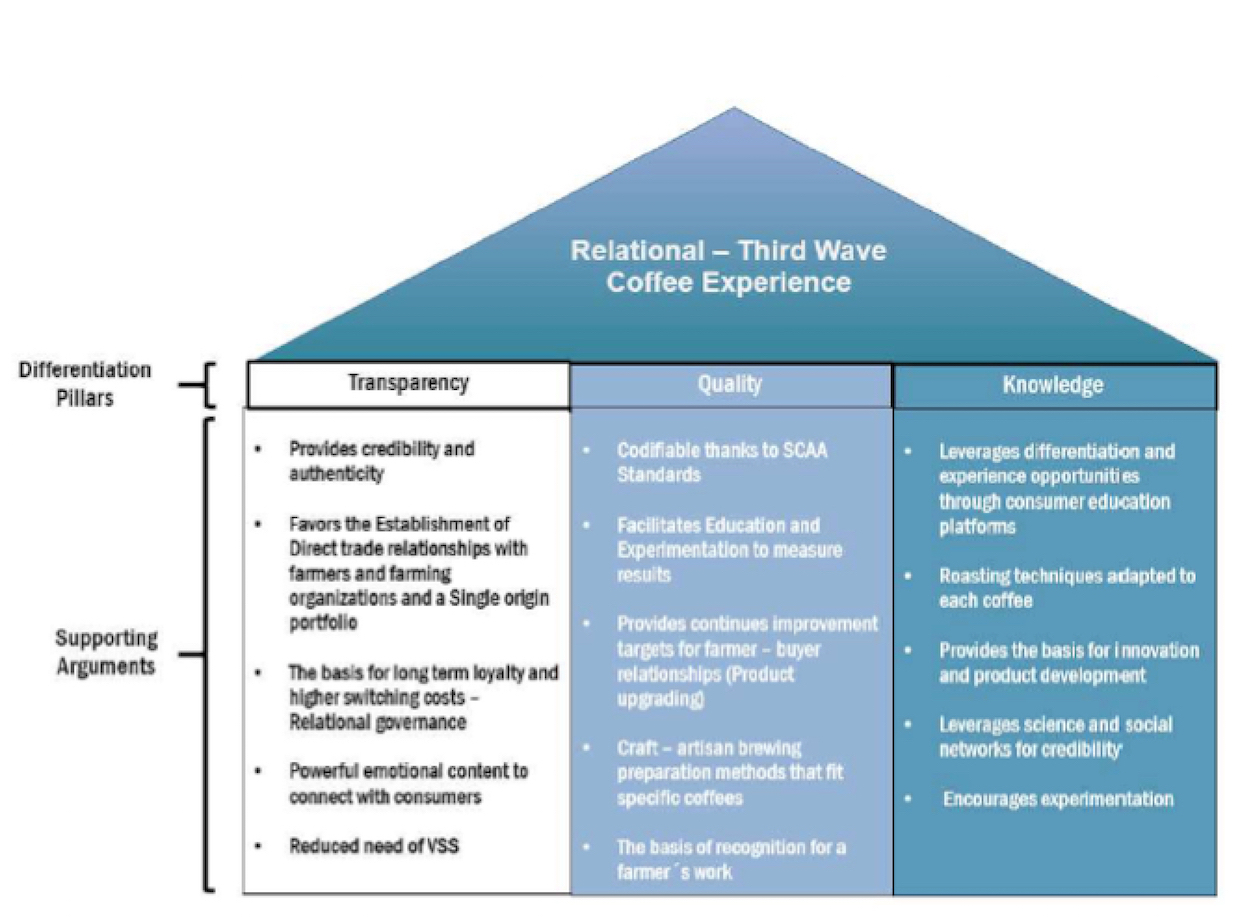

This more balanced model is found when independent coffee retailers or baristas decide to partner with individual growers or small communities for longer periods. Third wave brands achieve consumer relevance by providing transparency, higher quality, and knowledge about the beans and their preparation, a key part of the third wave artisanal experience (see graph below).

Many sophisticated farmers or strong producer Coops and farmer organizations have responded to the challenge, becoming part of product innovations in terms of growing new and exotic varieties or experimenting with different post-harvesting methods. Some even supply various types of content for marketing purposes, including pieces related to their sustainability programs and their impact, or emotional content to grow consumer engagement.

By not merely providing product, and by adding strong tools for differentiation, they are able to develop stronger ties that reach all the way to consumers, reducing the probability of being replaced next season.

Source: WIPO Working paper 39, “The powerful role of intangibles in the coffee value chain”

These successfully differentiated third wave models touch on the concept of a specific coffee being not just a commodity, but a key ingredient. In other industries, key ingredients are effectively becoming co-brands, leading to a new way of thinking involving “ingredient equity.”

Part two of this two-part story will delve much further into the concept of co-branding among producers and buyers, and how it might benefit all parties throughout the chain.

Any opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the author/s and do not necessarily represent the views of the Daily Coffee News or its management.

Luis F. Samper and Jan Anderson

Luis F. Samper is the president 4.0 Brands, based in Colombia. Samper is a former CMO of the Colombian Coffee Growers Federation (FNC) and co-author of number of publications on coffee, including “Juan Valdez, The Strategy behind the brand,” “The powerful role of intangibles in the coffee value chain” and “Towards a Balanced Sustainability Vision for the Coffee Industry.” Jan Anderson is CEO of Premium Quality Consulting, LLC, and is a consultant with experience in marketing, market research, analysis, and brand strategy. PQC conducts primary research in their proprietary data base of coffee brands in order to analyze changes in consumer preferences and industry trends in North America.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

This was a wonderful read. Thank you.

There is a lot of ‘glamorization’ in the coffee industry that constantly shifts focus away from the grueling work of growing and preparing beans. Slap an eco-friendly label on the bag, put up a photo of smiling farmers and you’re good to go! It’s very easy to get away with less-than-savory behavior and I’m happy sustainability conversations are becoming the new norm. At the rate things are going, there might not even be an industry to save in a few decades.