It is hardly breaking news that the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the specialty coffee industry, from farmers to baristas. We have witnessed how social-distancing measures have paused or disrupted coffee retail businesses, affecting coffee roasters, cafes and baristas.

But how is the pandemic, and the preventive measures taken by Latin American governments to halt the spread of COVID-19, affecting specialty coffee growers directly?

The harvest in Mexico and Central America ended just prior to the coronavirus reaching those countries. Hence, most farmers in Mesoamerica avoided many of the issues that South American farmers are now experiencing.

In Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, the South American origins where we at Caravela Coffee operate, the harvest is just getting under way. To better understand the primary concerns, worries, and challenges that coffee growers in these three countries are facing in the middle of the pandemic, last week our PECA team telephonically surveyed 379 coffee growers in Colombia, 48 in continental Ecuador, and 100 in Peru that have plans to deliver coffee this harvest.

Below are the results of the survey, where you can see coffee growers’ main issues and compare the different perceptions in the three countries:

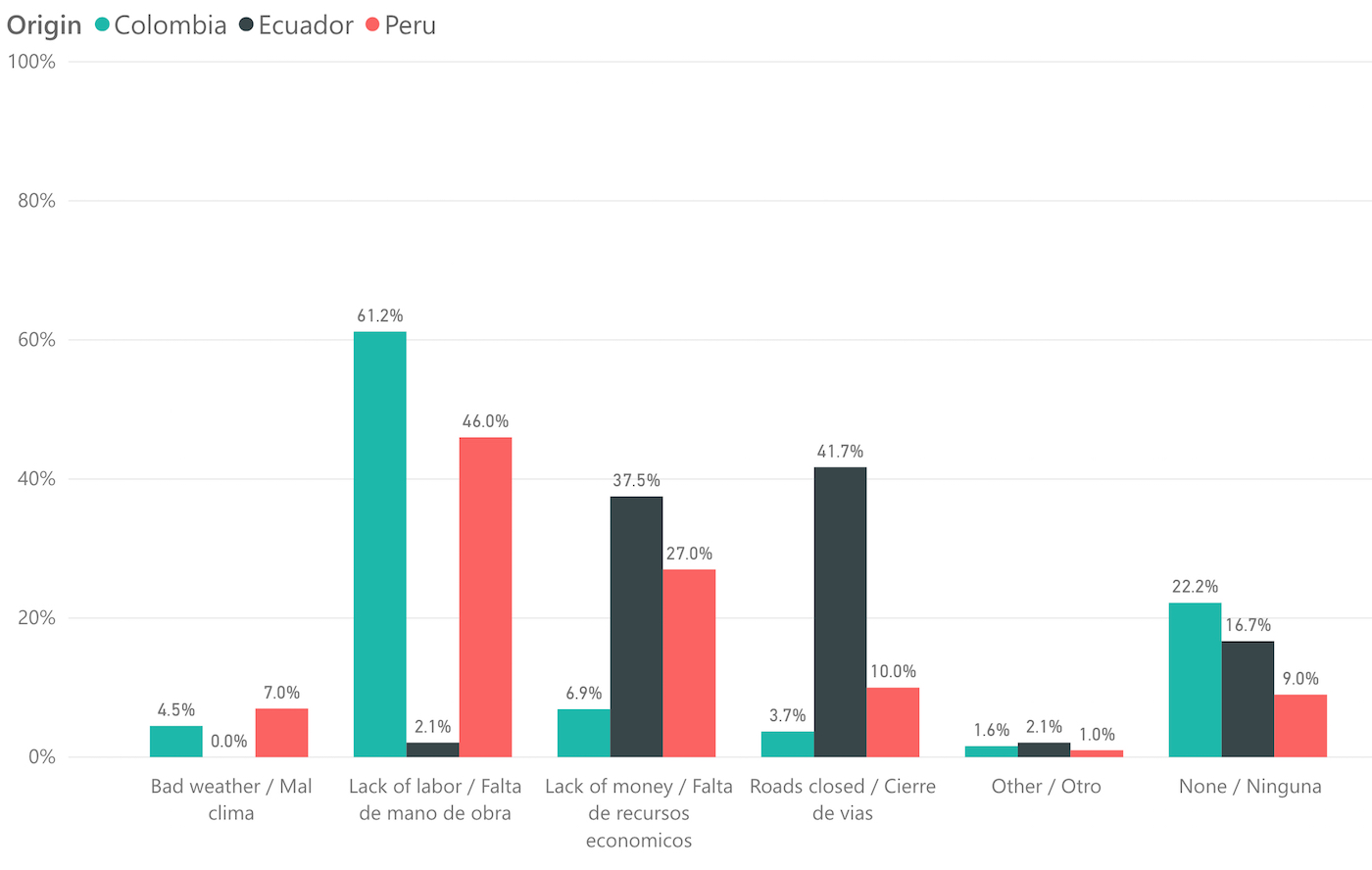

What are the main issues you believe you will face this harvest? / Que problemas que cree va a tener con la cosecha?

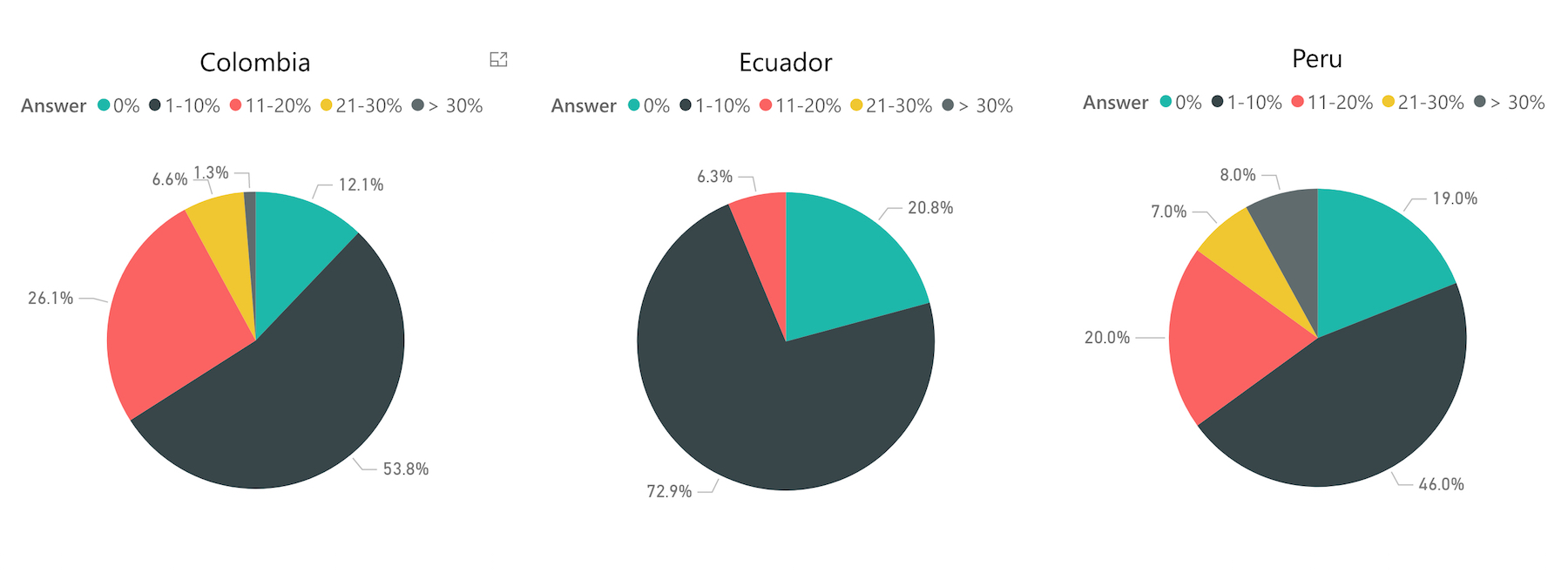

What % of the harvest will you lose asa consequence of the current situation? / Que % de la cosecha cree que va a perder por culpa de la situacion actual?

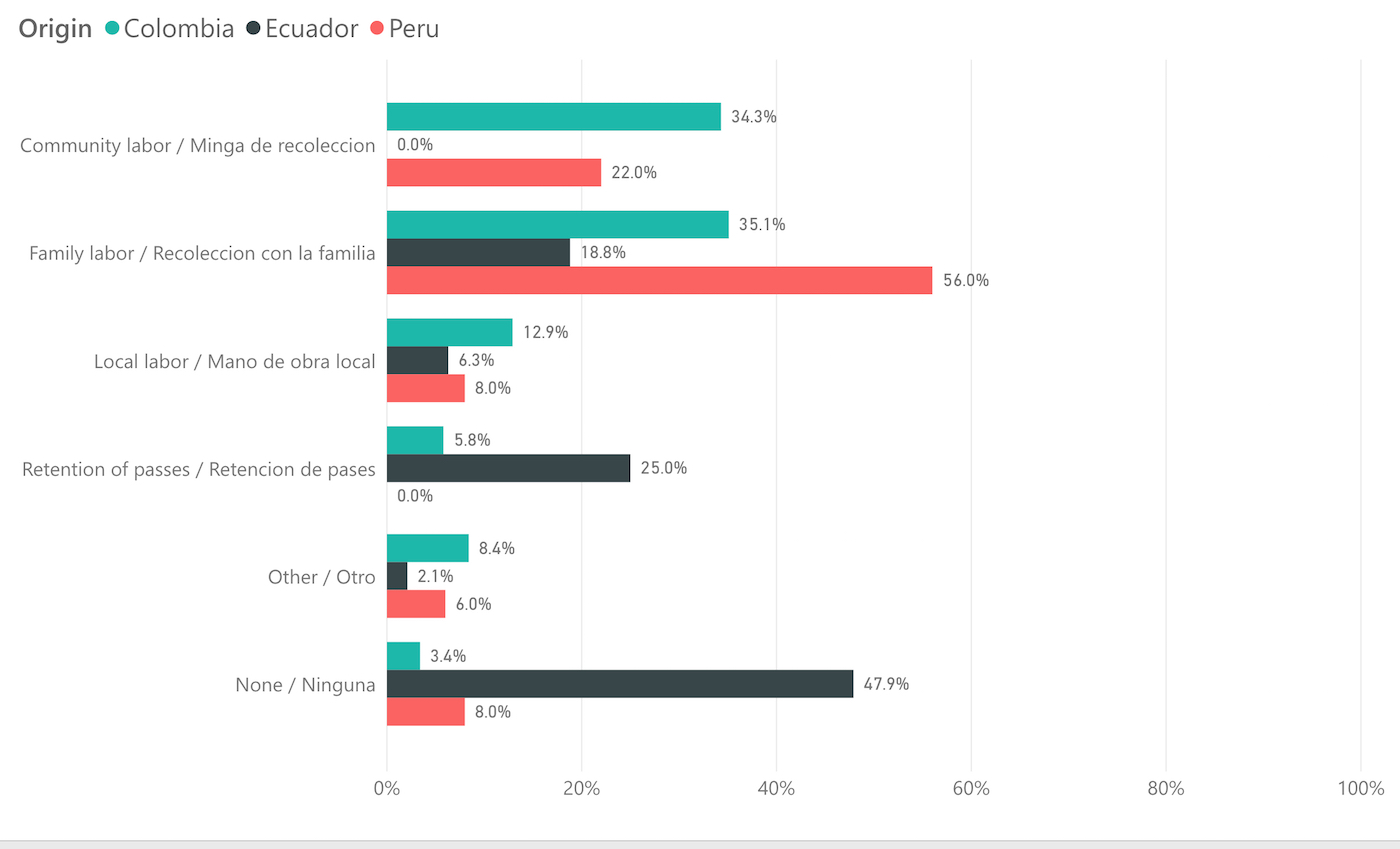

What strategies are you implementing to overcome the current situation? / Que estrategias esta implementando en su finca para superar la situacion actual?

Understanding the Results

The results of the survey show somewhat different issues affecting in each country. It’s interesting to observe that the pandemic, more than showing the impact of COVID-19 in coffee-growing communities, is highlighting the structural issues that each country faces.

For instance, lack of labor seems to be a bigger issue in Colombia and Peru than in Ecuador, as farms in the first two countries are generally bigger and more productive, thus more reliant on outside labor to be able to pick all their coffee. This issue is also reflected in the answers to the second question, as growers in Colombia and Peru anticipate a higher percentage of losses precisely due to the lack of labor.

Meanwhile Ecuadorian coffee growers seem significantly more worried than their neighbors about roads being blocked to prevent the spread of the virus into smaller communities. This response highlights the fact that the coffee industry in Ecuador lacks the type of solid coffee–buying infrastructure present in Colombia and Peru, where there is ample competition for parchment, purchasing stations located in almost every coffee community, and different types of actors, both private companies and cooperatives.

The survey also shines a light on the different cost structures, as our cost of production model has shown, where growers in Ecuador and Peru have higher costs of production than those in Colombia. This is due in large part to the pronounced devaluation of the Colombian Peso over the past few years, versus the dollarized economy in Ecuador and a strong Peruvian Sol. This is demonstrated by a significantly higher proportion of growers in Ecuador and Peru being worried about lack of money.

With higher costs, and lower yields and market prices, growers in Ecuador and Peru find it much harder to generate a profit producing coffee. This answer may also underscore the fact that the growers with whom we work in Colombia have stronger and longer relationships with coffee roasters, as we have been working in Colombia the longest, by far.

Despite the challenges faced by coffee growers, it is amazing to see how communities and families in Peru and Colombia are coming together to overcome the scarcity of labor that they are facing. We can see a huge increase in family members helping with the pickings, and communities creating mingas, where they unite for a common good and help coffee farms, to prevent community members from losing money or coffee.

Having this information helps us understand and analyze how we can help coffee growers in Latin America address their situation so they can continue producing quality coffee while earning enough money to make a living.

We must not forget these coffee growers during this difficult time, while buying as much coffee as possible from them at prices well above their costs of production.

Survey Information:

The survey was conducted via phone by our PECA team in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru from April 18-24. This is the detail of the growers interviewed in each country:

- Colombia: 379 growers with an average coffee planted area of 3.5 ha, from the departments of Cauca, Huila and Tolima (19 municipalities)

- Ecuador: 48 growers with an average coffee planted area of 2.56 ha, from the departments of Imbabura, Loja, Pichincha and Zamora (7 cantons)

- Peru: 100 coffee growers with an average coffee planted area of 3.2 ha, from the departments of Cajamarca and Cusco (11 districts).

Editor’s note: A version of this story initially appeared on the Caravela Coffee website and it is republished here with permission. Daily Coffee News does not publish “paid content” or “sponsored content” of any kind. Any views expressed in this piece are those of the author and are not necessarily shared by Daily Coffee News.

Alieth Polo

Alieth Polo is the Regional PECA and Sustainability Director for Caravela Coffee. PECA is Caravela's grower education program, which provides education and technical assistance to more than 4,000 coffee growers.

Comment