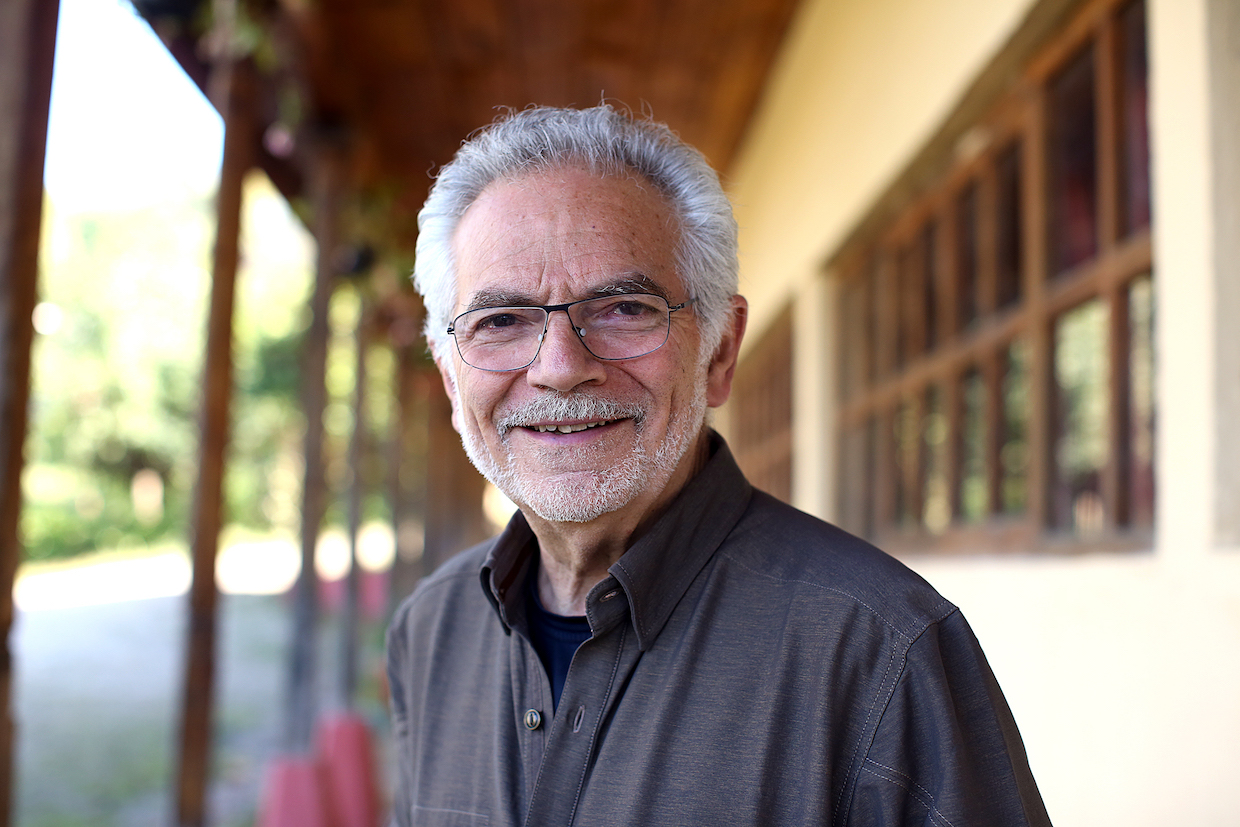

One of the United States specialty coffee industry’s original progressive voices and a longtime advocate for coffee producers, Bill Fishbein has witnessed some four decades of changes in the coffee trade.

Importantly, the 2002 Specialty Coffee Association of America Lifetime Achievement Award winner, Coffee Kids co-founder and The Coffee Trust founder and director has also witnessed decades of stasis, too.

“For years, along with many of my compatriots in the trade, I have been frustrated that despite the work that numerous organizations have done, including my own, things look pretty much the same for producers,” Fishbein recently told DCN. “Of course, there are examples of successful social ventures here and there, some extraordinary. But, despite the sustainable claims made online and on retail shelves, the overall conditions for producers has largely remained the same, or have actually become worse.”

Related Reading

- The Third Wave Myth: Inside a Marxist Takedown of High-End Coffee’s Value Structure

- Coffee at a Crossroads: Inside Jeffrey Sachs’ Landmark Sustainability Report

- Opinion: An Anti-Greenwashing Checklist for Coffee Practitioners

Fishbein’s own journey in and around coffee recently took another major step forward with the U.S. nationwide launch of Cocomiel (styled as “CocoMiel”), a for-profit importing venture designed to share profits directly with producers of green coffee and honey.

In the process of speaking to Fishbein about Cocomiel, DCN took the opportunity to collect some of his thoughts on the state of the coffee trade as he sees it today — in a period of thrilling social innovation alongside rampant greenwashing among coffee companies, consolidation among the world’s largest coffee buyers, and persistent price- and risk-related pressures put on the world’s coffee producers.

Here’s more from our Q&A with Bill Fishbien (interview has been edited and shortened for clarity):

Can you explain the need for the profit-sharing concept employed Cocomiel?

I don’t think of it as a concept. It’s my life’s work. A claim could be made that, while not alone, I have been developing this concept for the last 33 years…

It’s no wonder. According to MacroTrends, the commodity price of coffee in 1988 had an average closing price of $1.31 per pound, not adjusted for inflation through 2020. Adjusted for inflation $1.31 per pound in 1988 should have been worth $2.91 per pound today, and all premiums such as specialty, organics, etc., would be added to that $2.91, and not added to a paltry $1.11 per pound, which was the average closing price for coffee in 2020.

If the price of coffee had kept up with inflation and increased to $2.91, it would have had to increase 222% from 1988 to 2020. But, it didn’t increase 222% from 1988; it decreased 15% to $1.11/lb. And, the difference, adjusted for inflation, between where the price was in 1988 and where it was in 2020 is a difference of 262%.

Coffee prices for producers lost 262% from 1988 until 2020.

And, that’s still just the tip of the iceberg.

Even if the commodity price had kept up with inflation, it couldn’t accommodate producers for their arduous labor, their creativity, or their intelligence. It couldn’t accommodate their life sacrifices, the incredibly challenging circumstances in which they live out their lives, including natural disasters, environmental disasters, and sickening, yet easily preventable diseases, just to name a few. Despite it all, coffee producers still produce the world’s finest quality coffee.

Why can’t producers increase their price like other businesses? Most businesses set their prices as a factor of their cost of doing business. But, producers cannot increase their price to cover their expenses. Under the long-term paradigm, they take what they are given by commodity exchanges. They are told what to charge for their own products…

What about fair trade, you may ask? While I may offend some of my closest friends and allies in the trade, the word “fair” has given consumers a false sense of satisfaction that their purchases are contributing toward something that is fair for producers. Fair trade organizations have been vital to awakening the minds, the hearts and the wallets of consumers. “Fair-er” trade, yes. But fair? That’s quite a leap.

To be fair, fair trade cooperatives and associations offer a floor price for producers regardless of how low the commodity price may fall, and are guided by a set of principles that promote democratic principles within the organization…

But there’s nothing fair about the coffee trade for producers; and therein lies the rub: Why shouldn’t producers get their fair share of the gross profits that their products earn in the States? Specialty coffee has complained for years that the price of coffee is too low. But who is willing to pay more when they can pay less?

Beyond prices, what are some of the most important considerations for buyers in attempting to build more sustainable and responsible supply chains?

The single most important consideration that buyers should have is to get to know the producers. To do that, the buyers must listen to the producers and listen intently. They must listen without thinking about their commercial interests first.

Clearly, the buyers wouldn’t be meeting with the producers if they didn’t want to buy their coffee. However, once they know the producers, they need to make the decision whether they can develop, over time, a long-term, sustainable relationship with the producers based upon listening, trying to understand the producers and respect the people who are the producers…

Probably, the buyer should ask him or herself, if he or she is truly interested in a sustainable relationship or if they are only using the S-word to obtain a fluid line of supply.

It seems that one of the questions the “specialty” coffee industry has been asking itself is how to scale more sustainable business models, like the one that seems to be in place with Cocomiel. Is something like this scalable?

In 1988, when social issues began to carve their way into the specialty coffee market, the first reaction from the dominant trade was to be outraged. Many of us were called rabble-rousers, socialists, even communists. But, soon it became apparent that social issues were good for business. In a short period of time, every roaster had a cause coffee. Sadly, cause coffees did far more for merchants that they did for producers — but it was the beginning of something.

The specialty coffee trade itself was born from a small cadre of coffee roasters who were interested in quality. Price and profits were secondary. Shortly thereafter another small cadre of social entrepreneurs joined the specialty entrepreneurs, each adding the seeds of their ideas to something that had never been done before — new ideas focused on the quality of coffee and the quality of life for producers. Quality in several dimensions began to drive the specialty coffee trade.

In the meantime, the dominant trade was too busy making money and playing golf. Once quality of coffee and quality of life became fused, fast-forward 10 years or less and the specialty coffee trade had become the dominant trade. By then, heads were spinning in the former dominant trade as it tried to find its place in the quality movement.

Sadly, money and power often dominate every trade, and today specialty coffee appears far more interested in becoming bigger and bigger instead of better and better. Claims of sustainability are everywhere, often with little to back up the claims…

The good news is that today there is another small cadre of coffee people who are adding the seeds of new ideas to articulate what it means to be serious about a sustainable supply chain for coffee. If history repeats itself, what grows from today’s small cadre may someday become the dominant trade. Then you might just see heads spinning again.

So yes, the Cocomiel model is scalable, but it’s not just about the Cocomiel model; Cocomiel is one of a number of scalable efforts that one day could turn the specialty coffee trade on its head.

What are some of your biggest concerns these days about the way coffee is being bought, sold and marketed at large?

[The] wild sustainable claims by enormous businesses cannot be traced and tied to reality. They go unnoticed by the general public.

The continuation of commodity pricing and the practice of adding premiums for organics, specialty, etc., onto the seriously depressed commodity price.

In the name of direct trade, with absolutely no standards to back it up, buyers think they’re Indiana Jones, make one visit to origin and think they know the people they are buying from.

Reckless microlot purchases that encourage producers to work even harder to sequester the highest quality coffee from their best farmers getting a higher price for the microlot, but leaving the remainder of the coffee produced with less quality coffee because it was swept away in a microlot. The remainder of the production left may be of lesser quality and commanding a much lower price. This recklessness works for merchants at the expense of producers. This is not true for all microlot purchases, just reckless ones, and, it does concern me.

What are your thoughts on the recent movements towards transparency on pricing in the coffee industry? Could this be beneficial to producers? Is it potentially counterproductive?

At this stage it appears to me that this is a giant leap forward toward more accountability and the transparent exposure of fraudulent claims. I think it’s a good thing.

What’s next for you? How do you hope to grow Cocomiel? And do you have any other plans/ventures in the works?

I plan to actualize the Cocomiel model in any way I can. I plan to slowly add products to our current line of supply, sharing import profits, wholesale profits and retail profits with producers along the way. I don’t plan to build Cocomiel into a huge business. I’ve always been more comfortable rolling up my sleeves in the mud rather than sit around a conference table.

I hope that others will see what Cocomiel is doing, replicate it and improve upon it. If Cocomiel should become one of those seeds that grows, evolves and joins the myriad other efforts toward a more sustainable, equitable trade for all, I would be extremely pleased. But seriously, if that were to occur, it probably wouldn’t happen in my lifetime. I am very happy doing what I am doing having faith that there will be something of value at the end of the rainbow.

Nick Brown

Nick Brown is the editor of Daily Coffee News by Roast Magazine.

Comment

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

Yup Bill has been around a long time, and been right in the thick of it most of those years. Sadly he’s part of a diminishing lot of such people. He’s seen some things, and has gained some wisdom along the way that the industry needs.

I’ve personally always been mysitified at how the entire commodities exchange works, and what “good” it does.. except for those insiders that know how to play the game well. HOW can some guys sitting in an office somewhere, theyr hands clean and all, decide what a given product (be it coffee, tea, steel,oil, copper, silver) sell for in three months? FUrther since I’ve been involved in coffee (about 15 years now) how does coffee, a very much varied product, get treated like a standardised product such as copper or #1 light crude oil? It cannot. And should not be.

Granted when the coffee exchanges were begun, coffee WAS a more or less uniform commodity, but it was raised and handled pretty much like wheat or barley. Small round thigns to fill up the holds of cargo ships. Take it to San Francisco, unload it in bullk, and the massive roasters would fill the air with the roasting smoke and put it all into round cans and onto the stores at Safeway and Purity.

But this product is NOT the product in which WE deal, is it? So WNY has the whole exchange pricing system been alowed to persist for a produt that is so radically different? Let the folks represented by the green androgynous mer-person contunie to buy the commidoty grade stuff, governed by the C market price. sUre, they claim to have some “specialty grade” offerings. Those few Ive tasted were not, but that’s a side issue. I can buy Bimbo white sliced bread for about a buck a loaf, at the same place I can take a loaf of Dave’ Killer Bread and put THAT into my cart…. for a premium of about four times the Bimbo price.

WHY is our product not treated the same way as these widely varied offerings, all with their place on the shelves?

NO business or industry can survive and prosper wholst ignoring the simple equations involved in COGS and fixed costs and margin and bottom line. WHY is this standard practice suddenly treated like the proverbial baby and now had out along with the bath? I have known, perosnally, some producers.. Cup of Excellence lever producers. I had a very precise picture of whta they expend to fill up those five bgs of the microlot I wanted….. and the ‘standard grade” coffees as well. I had n o issue paying them their asking price, knowing they had run their numbers and knew what it cost to produce and deliver. I added ny nickel to the landed cost, and resold it, green and/or roasted, and did fine. Those nuimbers I paid were many multiples of the then-C grade price. But then, we all KNEW none of their products were anyting like what Hills Bros, Boyd’s, or MJB were proffering.

Until the Specialy industry separates from the commodity grade industry this issue will persist. There will be those who purchase C lots, figure out how to roast it well, and blend for good presentation, and market it as whatever they can convince their customers it is. So what? Let the tastes of the consumers decide. But the producer priced it per their protocols, the purchaser bought with those in view, he added value by his own decisions (roasting, blending, preparation, packaging, presentatioin, etc) and resold it. If the guy selling it thought it was worth more he could have asked for it… and gotten it.. or not. Price is that which determines the distributioni of scarce resources that have alternate uses.

Great Comment! How come the talk is always about the C-market but we don’t discuss differentials and how high quality coffee fetches hefty differentials.