A worker harvesting coffee in Colombia. Photo courtesy of Those Coffee People.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, the trajectory of Colombia’s internal coffee prices has defied expectations.

The abrupt collapse in oil prices in March 2020 triggered a near 25% reduction in the value of the peso (COP) against the dollar. As coffee beans are purchased in dollars on international markets, the industry was able to benefit from the exchange rate arbitrage. However, even as the peso recovered some of its value against the dollar, internal coffee prices remained high over the previous 14 months.

Now, with the ongoing civil unrest causing significant disruption to supply chains across the country, prices have once again spiked. The price offered to producers by the growers’ union the Federacion Nacional de Cafereros de Colombia (FNC) in early May hit an all time record of COP 1,440,000 (US$386) per carga (125 kilograms), a 34% increase since the start of the year.

What’s even more remarkable is that directly prior to these record-high prices the industry was beset by years of financial pain, with producers struggling to make a living, and many abandoning coffee farming altogether.

This ultimately prompted the Colombian government to intervene in the market by guaranteeing producers a minimum floor rate through a price stabilization fund. However, thanks to continued record prices, the fund hasn’t been touched since its inception.

Internal Prices and the Stabilization Fund

Despite Colombia being the third-largest coffee producer in the world, production is fragmented, with more than half a million smallholder farms, known as fincas, scattered across the country. The majority of these fincas do not produce sufficient quantities to sell directly to private buyers, so instead sell to an intermediary, typically the FNC or a local cooperative.

Both the FNC and local cooperatives offer a floating internal buy rate to producers. A number of factors influence the price that’s offered, beyond just supply and demand. These include the value of the peso against the dollar, as well futures contracts that need to be filled.

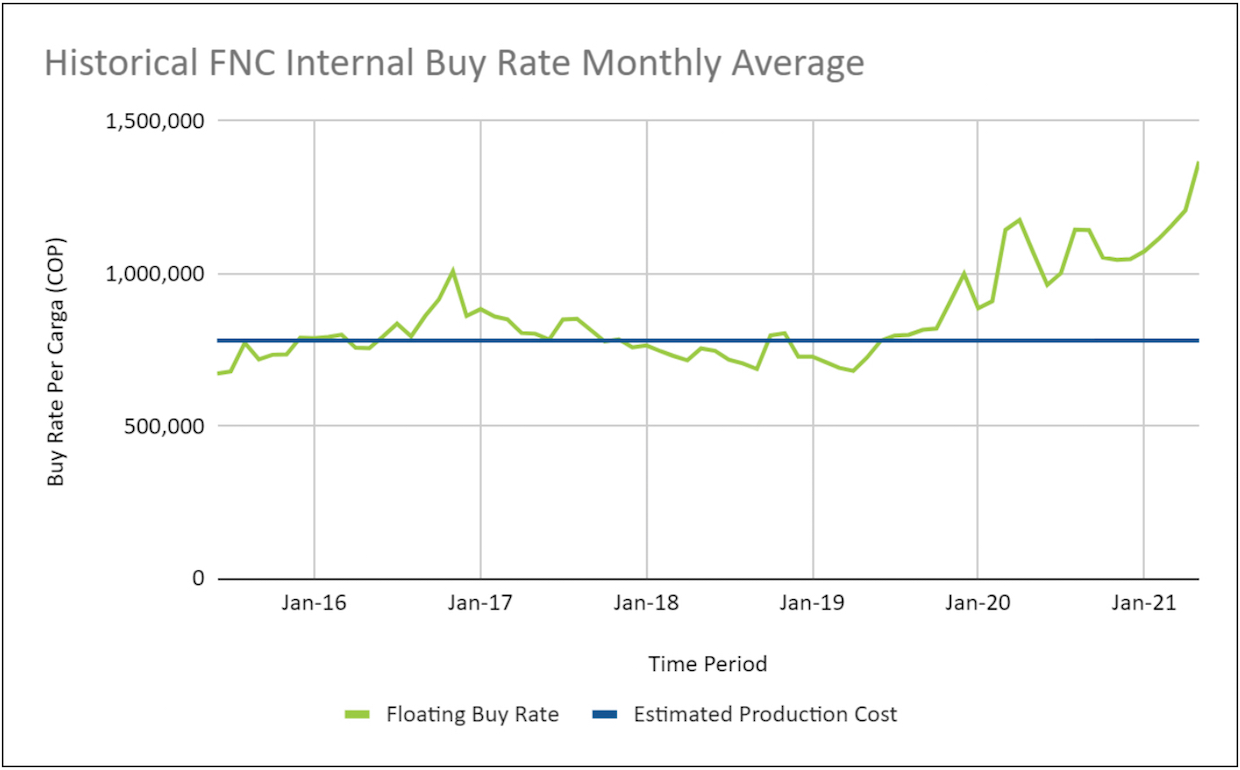

Unfortunately for producers, buy rates have frequently dropped below the cost of production, with the second half of the previous decade being a very difficult period for the nation’s smallholder farmers.

Data source: Federacion Nacional de Cafereros de Colombia

The Colombian government launched its landmark price stabilization fund in March 2020. The $64 million fund was designed to shore up the FNC’s internal buy rate whenever it drops below the cost of production, thus guaranteeing producers can always sell at above cost.

An Unprecedented 14 Months

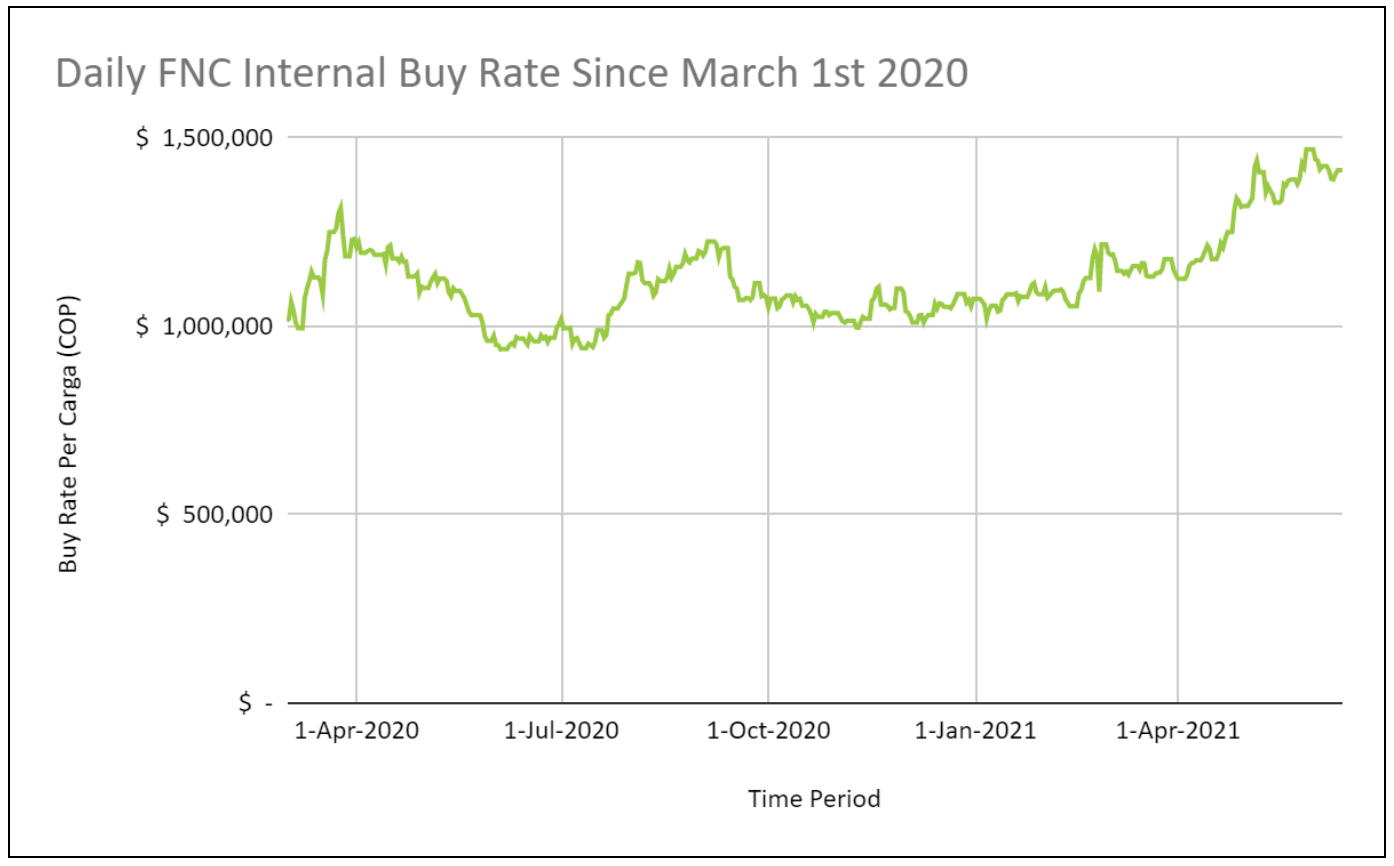

Price recovery took hold from the middle of 2019 onwards as the internal buy rate moved above the estimated cost of production. However, it only began its rapid ascent at the beginning of the pandemic, smashing through the psychological barrier of COP 1 million and hitting a peak of COP 1,315,000 (USD $352) in late March 2020, which equated to a 35% increase versus the beginning of January of that year.

Aside from the drop in the value of the peso against the dollar, a number of other factors had an inflationary impact on prices in 2020. This included lower yields in neighboring Brazil due to inclement weather and a reduction in export volumes across Central America, which created a supply squeeze across the region.

Now, as the industry is approaching the peak of the smaller mid-season harvest (known as the traviesa), the FNC internal buy rate has been rallying once again. Since the beginning of the year the price has increased by 34%, hitting an all time record of COP 1,440,000 (USD $386) per carga in early May.

Initially, this price increase was driven by the impact of La Niña — an irregular climate event that started last September and is forecast to continue until the middle of 2021 — which may cause higher than average rainfalls in the region, potentially reducing yields and squeezing supply.

However it’s the civil unrest that’s been convulsing within the country since the end of April that has pushed the internal buy rate to an all-time high. Just eight days after the protests began on April 28, the price jumped again by 8% to hit a new high of COP 1,440,000.

With road transportation having been paralyzed across parts of the country, suppliers have been concerned about being able to fulfill orders, meaning ever higher-prices are chasing a diminishing supply of coffee.

Looking Ahead

Protests and civil unrest are continuing across the country, including significant disruption in Buenaventura which is home to one of the most important Pacific seaports on the continent, accounting for 60% of all Colombian sea exports. Many highways also remained blocked, meaning coffee destined for export remains stranded. Therefore, the short- to medium-term outlook remains uncertain.

If the situation continues as is, with transport infrastructure blocked, then this will collide head on with the peak of the smaller “travisea” harvest season taking place in parts of the country in June and July. If this happens, prices may continue to climb, with the next psychological barrier of COP 1,500,000 very much in sight.

Looking beyond the impact of the protests, producers have enjoyed an unexpected windfall since the beginning of last year thanks to continued high prices. However, there is some concern that complacency could set in if the longer internal buy rates remain high.

For one thing, abnormally high prices may disincentivize some producers from switching to higher-value specialty crops — a stated development objective of the FNC. Switching from commercial to specialty grade coffee can give producers more economically sustainable footing in the long-term, though there are risks involved. Meanwhile, the FNC is paying producers record prices for commercial-grade crops.

It is impossible to predict the future direction of prices. Yet as recent history has shown, prices can go down and stay down for prolonged periods of time. With the impacts of climate change and COVID-19 also added into the equation, we might reasonably expect continued market volatility.

Unfortunately, producers still confront a host of barriers to their economic security, which means they have very little to fall back on should the market experience a sudden fall in prices. While the government is presently providing a safety net in the form of the price stabilization fund, the ability of this mechanism to do what’s required in times of need remains untested.

This story was written for Daily Coffee News by Jennifer Poole, co-founder of Those Coffee People. Daily Coffee News does not publish “paid content” or “sponsored content” of any kind. Any views expressed in this piece are those of the author and are not necessarily shared by Daily Coffee News.

Jennifer Poole

Jennifer Poole is the Co-Founder of specialty Colombian coffee supplier Those Coffee People. Based in Medellín, Colombia, Jennifer spends her time traveling to remote towns and villages in search of the best specialty coffee the country has to offer.

Comment

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

Very good article, impressive, I am a marginal Coffee producer from South India.

Single origin , arabica speciality coffee.

I think it is important to know and understand where the referenced cost of production comes from because It has been my experience as a coffee producer in Colombia that even these record high prices are still way below the cost of production. The SCA with Azahar have been trying to create a new cost of production that I actually see as being closer to reality. Record high prices does not mean that producers are actually making a living wage.