Taza Presidencial Producers organized around Cooperativa San Juan and Lata 16 lab. Photo by Contento Estudio (@contento_studio).

One day last November I was working at The Crown in Oakland when I received a call from Felix Chambi Garcia, who oversees quality control and exports for Bolivia-based Cooperativa San Juan. It was regarding Bolivia’s 7th annual Taza Presidencial coffee quality competition.

“You’ve been invited to participate as a judge,” Felix said.

I was over the moon, but the timeline was tight. One week later, Felix was picking me up from the international airport in La Paz, Bolivia’s executive capital city. Within two days, I found myself on the open-air patio of the Hotel Wara, where the Taza Presidencial was to be held the next day. The patio had been transformed since I’d seen it earlier that afternoon: Dining tables and chairs used for breakfast service had been replaced by long tables covered with coffee samples.

I was standing with Mary Luz Condori, a former cacao producer who entered the coffee industry in 2006. She now co-owns Geisha Coffee House in La Paz with a group of three other like-minded women who all produce coffee.

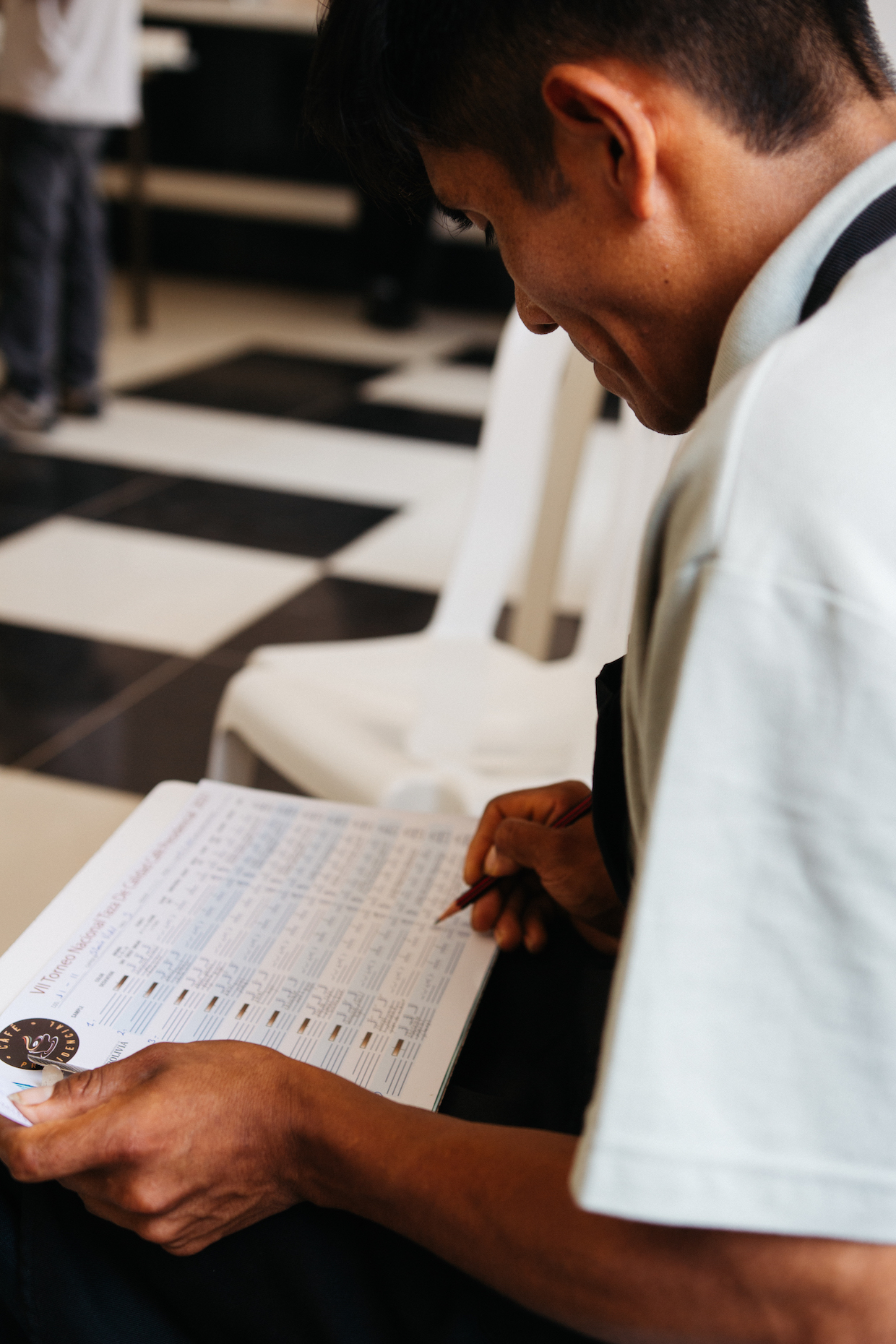

Judge Simon Vidal. Photo by Contento Estudio (@contento_studio)

Mary Luz has been involved in the Taza Presidencial since she was a founding member of the event in 2015. Over the years, she’s participated as an organizer, a coordinator, a spokesperson and a scorekeeper. This most recent year, having reached the highest score in her cohort during the judging application process, she became the 7th annual Taza Presidencial’s Head Judge.

“My whole life I’ve tried to collaborate with producers from my different areas of professional expertise, all to continue promoting the market for Bolivian coffee,” Mary Luz told me.

The Competition History

The Taza Presidencial quality competition was created by coffee producers themselves, through the Federation of Coffee Producers and Exporters of Bolivia (FECAFEB) and National Association of Coffee Producers (ANPROCA). Both organizations sought to promote their products to national and international markets, while obtaining support from the Ministry of Rural Land Development.

The Cup of Excellence, which took place in Bolivia from 2001 to 2009, served as a model for this new, wholly Bolivian tournament. Coffees that enter the Taza Presidencial go through a physical green and cup defect evaluation before moving on to the four phases of competition: a pre-selection/elimination round; the national jury round; an international jury round; and, finally, the virtual auction.

Judging Taza Presidencial

On a hot and humid November 2021 morning in Caranavi, in the region of Los Yungas, the international jury phase of the Taza Presidencial kicked off with opening ceremonies — a flurry of events including remarks from local, federal and coffee sector dignitaries, a powerful monologue called “Yo soy la constitución” from an elementary school girl, and a “coffee dance” featuring the recently crowned Miss Café Caranavi.

International guest judges from Germany, France, Czechia and the United States were included in the panel this year. I was surprised and honored to be offered the role of International Head Judge. With the help of Mary Luz, I began leading this phenomenal group of judges.

Next came calibration. The Taza Presidencial uses the Cup of Excellence cupping form, which Bolivians seem to prefer for most cuppings. I translated the training resources I found into Spanish and led a bilingual lecture, going through each section of the form and what different scores meant.

7th Annual Taza Presidencial International Head Judge and story author Sandra Loofbourow. Photo by Contento Estudio (@contento_studio)

“The CoE forms allow us to explore the coffees in a competitive way, unlike the SCA form which is more suited for use in a laboratory,” said Mary Luz. “It helps us rank high scores, because after all, that’s what we’re looking for – a ranking, and a winner.”

In fact, Taza Presidencial has the express goal of finding coffees that are “presidential,” meaning they score 90+ points. In 2021, only two of the top 44 coffees evaluated in the final round reached the 90-point mark.

The winner, a coffee produced by Juan Calani Vargas, had a final consolidated score of 91.45 points, and the second place, Lucia Nuñez Alvarez’ coffee, was awarded a 90.40.

In previous years, the council overseeing the tournament only shared the scores of the top 10 coffees, fearing misunderstandings and complaints. Now, given the increased participation and broad range of coffees in the event, all scores and information are published for all lots making the final round.

“We’ve seen some really important advances in this competition,” said Mary Luz. “There’s been a huge increase in participants; we’ve seen many different processes — naturals, Kenya process, anaerobic, and even newer processes. These coffees are being handled with even more technical experience than before, including storage practices after processing.”

Regional Diversity

The 2021 winner is from Cochabamba, an area South of La Paz. The win represents something of an upset, since the region of Caranavi produces most specialty coffee in Bolivia — between 80-90% percent of the country’s total production, depending on who you ask — and usually takes the top spot.

The Taza Presidencial has in fact seen an increase in regional participation in recent years. Among the 261 total samples entered into the competition, regions represented included Caranavi and Cochabamba as well Santa Cruz and La Asunta. Despite the relatively lower levels of production among those latter regions, clearly they have found success in cup quality.

Another reason Cochabamba’s victory this year is so important is that the area is also known as a major producer of coca — especially for the illegal market.

“A coffee from Cochabamba winning tells us that producers are turning towards an alternative, legal crop to generate income,” said Mary Luz.

Judge Wilfredo Calles. Photo by Contento Estudio (@contento_studio)

The fact that this year’s winner was a Catuai variety was another notable surprise. While Catuais have been cultivated in Bolivia in since the 1980s, they’ve been overshadowed in recent competition years by varieties such as Geshas, Javas and Pacamaras, which are more recent arrivals to Bolivia.

“This shows that quality doesn’t only come from variety production, but primarily from post-harvest processing,” said Mary Luz, who noted that Juan Calani’s family has been honing their processing methods for the last several years with the express goal of winning the competition.

The Auction Evolution

When the tournament first started in 2015, it ended with an on-site traditional auction the day after the competition ended. A small handful of foreign businesses were invited to participate, as were the judges. Due to low participation and limited success, the tournament collaborated with the Ministry of Foreign Relations to create an electronic auction the following year. Now, companies both foreign and domestic are invited to sign up for the auction by creating a login on a government website. Bids continue for two days before closing on the morning of the third day.

Along with the top 10 winners of the Taza Presidencial, coffees that scored above 86 points were included, up to 21st place this year. Each of the coffees being auctioned gets a technical write-up explaining its exact origin, cup profile, score and processing details. This information is posted publicly on the auction website. Plenty of other resources are shared there as well, including rules and regulations, judge selection process, and each judge’s profile.

There is a scheduled end time on the final day of the auction. However, if there is activity on any coffee, the auction will be extended in increments of 10 minutes until bidding ceases. In 2021, the auction was extended by more than four hours to allow buyers to keep pushing prices.

Taza Presidencial makes wins at home

While the competition’s goal has always been to better promote Bolivian coffee on both the domestic and international markets, the biggest returns have come from Bolivian buyers.

In 2016, a roasting company with two cafes in La Paz bought the first-place coffee. In 2020, that same company set record prices for the winning coffee, bidding $160 per pound on a lot of Gesha from La Paz.

For the organizers of the Taza Presidencial, this felt like a huge win; they had finally garnered the attention and respect of industry professionals in their own country, who were willing to pay not just fair, but extremely high prices for excellent Bolivian Coffee. The bidding for the first-place coffee is still fierce, and each year the auction features many Bolivian buyers vying for nearly all the winning coffees.

Taza Presidencial has also succeeded in including members from across the supply chain in its competition. Starting in 2016 they began promoting the participation of baristas through certification in SCA courses for the first time. That year, 21 baristas were certified at the intermediate level; now, Bolivia boasts numerous in-country AST instructors.

“We feel that the baristas are important agents in the promotion of Bolivian coffee, because they are the ones in direct contact with the customer,” Mary Luz said. “They are the ones who will transmit information about origin, about cup profile, about different processing methods to the customer.”

What’s next?

International engagement remains somewhat limited. The government often lacks the funds to sponsor judges from foreign countries without more consistent interest among buyers. Still, there are a few consistent supporters, including France-based Belco and U.S.-based Café Kreyol. This was Royal Coffee’s first year participating, and the sheer quality and variety of coffee that was cupped at the Taza Presidencial has sealed Royal’s interest and investment in this origin.

After studying, sampling, and buying Bolivian coffee for the past two years, this trip confirmed what I already knew: Bolivia is on the rise as a coffee origin.

They have the quality, technical know-how, infrastructure, and drive to produce phenomenal coffee. They’ve already achieved production of truly exceptional lots, and each harvest seems to taste better than the last. With projected increases in volume, I look forward to seeing Bolivia become a staple on specialty coffee roasters’ shelves. In the meantime, I’ll continue relying on the Taza Presidencial to find the best coffee this origin has to offer.

Mary Luz is proud of what the tournament has achieved so far, though she’s looking forward to continued growth.

“This is a wholly Bolivian project, made by the producers themselves. It’s ours, and we must feel proud of this undertaking and continue improving the process so that the whole value chain can be integrated, from production all the way through to the final customer,” Mary Luz said. “We want to transmit the feelings and thoughts of the producers, and of all of us who are involved in the coffee industry in Bolivia.”

Sandra Elisa Loofbourow

Sandra is the Director of Coffee Content for The Crown, a certified Q Grader and Assistant Instructor, and a Q Processing Generalist. She brings with her a depth of experience as a roaster, green buyer, and barista. Sandra is co-host of the bilingual podcast Cafetera Intelectual and chair of the Good Food Awards Coffee Committee. She is passionate about all things delicious and dedicates time to time eating cheese and sipping IPAs.

Comment