In 1988, our in-house research clearly showed that grinding fresh coffee for each order (on-demand grinding) yielded the best results for true artisan espresso. Yet designing grinders to do this perfectly has been a persistent challenge for the coffee industry.

It has been four years since I first issued a call to action regarding espresso grinder design. However, if we as a global industry seek to truly and consistently elevate espresso craft and art, the need for solutions remains just as dire, and the call to action should be even louder.

This piece revisits some of the concepts introduced four years ago while taking into account newer innovations and technologies.

[Editor’s note: All views expressed in this piece are those of the author and are not necessarily shared by Daily Coffee News or its management. Daily Coffee News does not engage in sponsored content of any kind. The author claims to have no affiliations with any of the companies mentioned in this article that would result in financial gains from publication.]

Why innovation is needed

When the grind is properly adjusted, the grinder design is responsible for the quantity of flavor in the cup. The coffee’s roast and freshness, the espresso machine, barista techniques, water quality and the environment in which you are brewing are collectively responsible for the quality of that flavor. And with most of the grinder designs available today, up to 40% of the volatile aromatic compounds (the flavor) ends up in the dumpbox.

The situation is reminiscent of the efforts I made to stabilize espresso machine temperatures in the late 1990s. Machines would vary wildly on the temperature of the brewing water, often resulting in light-colored, bland shots. However, temperature stability was an improvement that was easy to demonstrate. When the brewing water temperature stabilized, the crema was a beautiful deep red/brown — even if the temperature was off a little.

Then at La Marzocco in Ballard (Seattle), on February 28, 2001, we crossed that barrier. With the help of La Marzocco engineers and John Bicht, the genius who runs Versalab, we prepared espresso on a PID-controlled 2 -group Linea, and I tasted the fragrance in the shot for the first time.

With my article “Italy Meets Omega” (pdf link) the global PID revolution — beginning with Mark Barnett’s Synesso — was underway in espresso machine design. Presently, PID control is the worldwide standard for artisan espresso preparation.

As I mentioned above, with PID the result was easy to see in an average espresso shot. The color was a deeper red/brown and crema was luxuriously thick.

The grinder situation is more subtle. You have to very good at preparing espresso to see that a fast grind produces shots that are thinner, and less flavorful, than shots that are ground with the ideal RPM.

Of course, manufacturing any new machine is an incredibly expensive process, so what follows is an attempt to reassure coffee equipment manufacturers that the market is ready to accept more innovation in on-demand grinding. There are many useful, problem-solving grinders and accessories currently in the marketplace, yet in my opinion not one of them checks each and every box required for perfect espresso.

My hope is to reach expert baristas — from Seattle to New Zealand to China — to implore them to raise their voices and demand on-demand grinders that meet each of the following criteria.

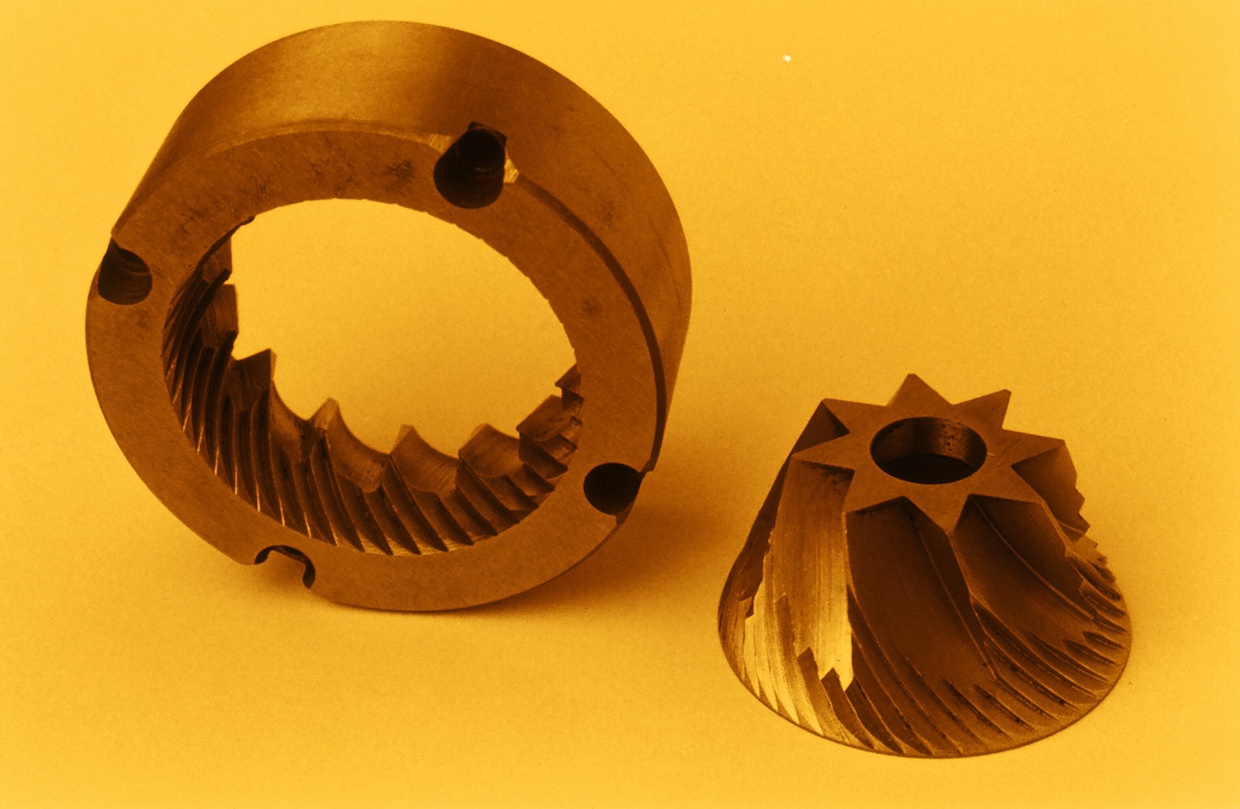

Conical or flat burrs?

Flat burrs are preferred by many experienced grinder manufacturers because they produce a much more uniform grind. The fine particles are difficult to handle within the grinder without being pulled out of place by static forces. This makes extraction easier to dial in for the barista, and more consistent, but lacking in body and richness.

Our preference is for conical burrs. This style of grinder burrs produce fine particles, which can add richness and flavor to the shot. As the bean enters the burr, the heavy veins crush the beans. When the beans shatter, they produce finer particles along with bigger pieces. Then the bigger chunks are sheared to a uniform size by the by the fine teeth, much like flat burr. But the fines remain and produce much richer and thicker shots.

Head speed, RPM

The proportion of fines varies with the speed of rotation of conical burrs. Our research — using the Kony Burr manufactured for Mazzer, measured at 38mm I.D. on the ring section of the burr — shows a sweet spot at about 300 RPM.

I have tested grinders turning a conical burr at 125 RPM and the coffee was thin, like a flat burr extraction. Similarly, grinders turning the conical burrs too fast also produce thinner shots. In manufacturing, the ideal RPM must be determined for the conical burr chosen. Detecting this difference requires expert barista technique and precise control of brewing water temperature.

Ground coffee retention

The coffee beans still retain some moisture after roasting. In our blend at Vivace, we see that coffee grown in Brazil contains the most moisture and therefore requires a more coarse grind setting to achieve the desired flow rate of the espresso shot. Ironically the Monsooned Malabar, after soaking in water a couple of weeks, contains the least moisture in the roasted bean, requiring the finest grind.

The tricky part is that ground coffee is wildly hygroscopic, exchanging moisture very rapidly with the ambient air. Any ground coffee trapped within the grinder will desiccate quickly as it sits in the warm grinder. Thus, that amount of powder will pass the brewing water through more quickly compared to the original, speeding up the flow rate of the espresso, and giving the barista headaches as they struggle to retain the ideal languid, slow pour.

Manufacturers are beginning to recognize this and build machines that do not have chambered coffee trapped inside. They advertise zero retention, but in my experience, there is only one grinder that truly eliminates ground coffee retention in the dosing path: Etzinger’s jet dosing system.

Products such as ionizers that standalone or built into grinders are coming on the market. I have not worked with these systems, but I am highly skeptical that they will work in all environments. In my direct experience, only consolidating the powder assures 100% particle integrity of the fines in the mix.

Dosing the ground coffee

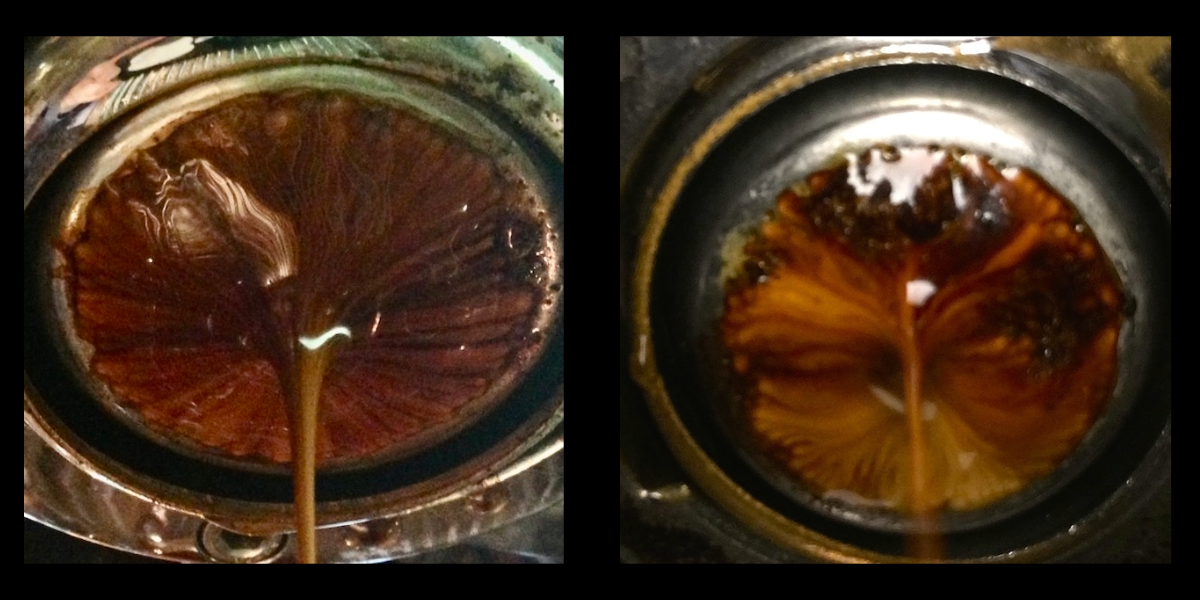

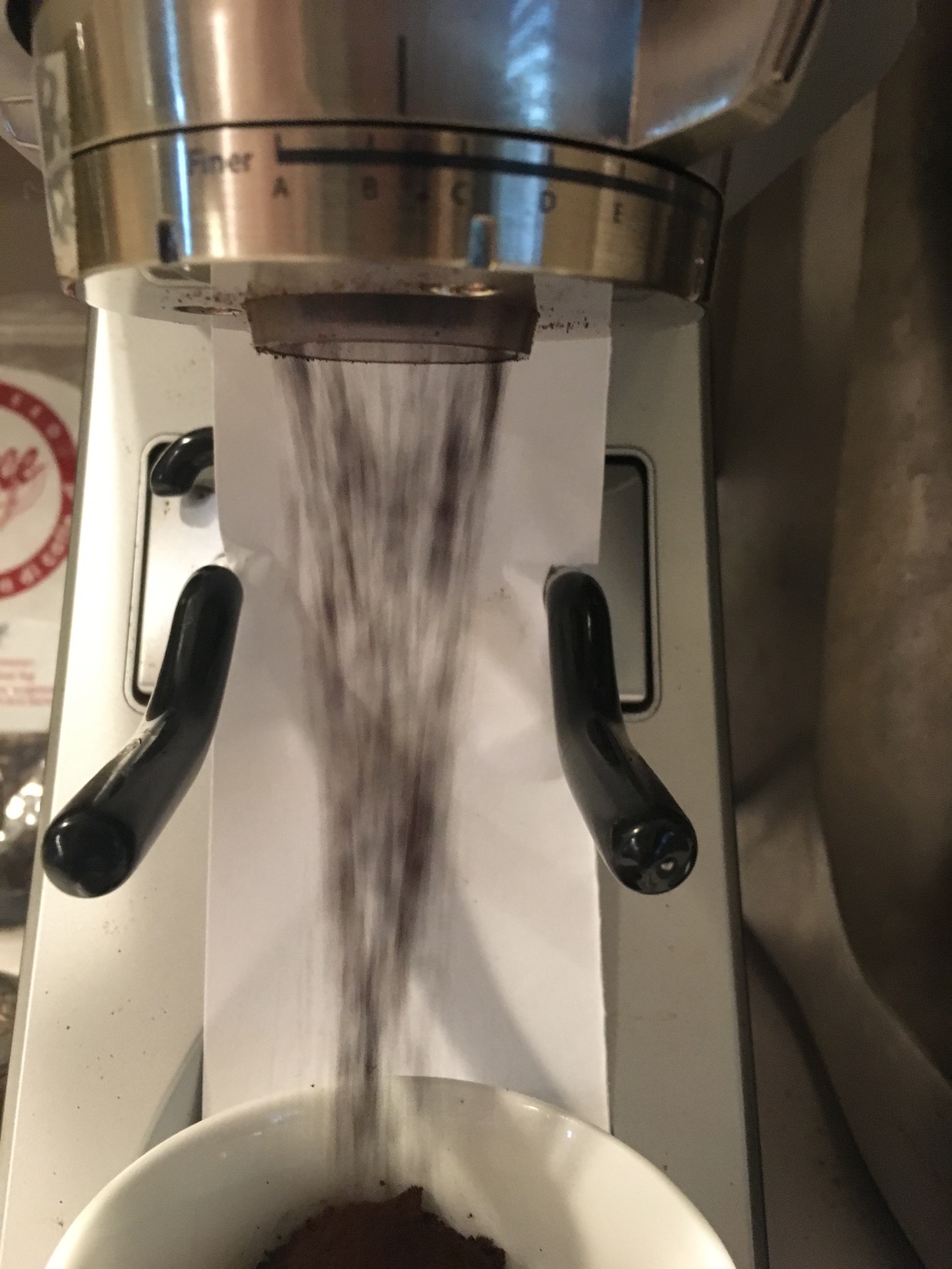

When the coffee first exits the burr set, the fines are distributed evenly within the powder. To have an even extraction, the fines must retain the integrity of their distribution within the ground coffee. However, on the path to the portafilter, the fines can be easily pulled out of their original distribution with the slightest exposure to static charges. This produces an uneven extraction as shown in these two images.

Good shot (left) vs. bad shot (right). Free-falling coffee within the grinder en route to the portafilter produces an uneven extraction.

In the above images, the machine, coffee and barista are identical. The only difference is the prototype grinder. I have worked on two occasions over the years with La Marzocco to mitigate static on new grinder designs, and I have tested several new grinders claiming zero retention.

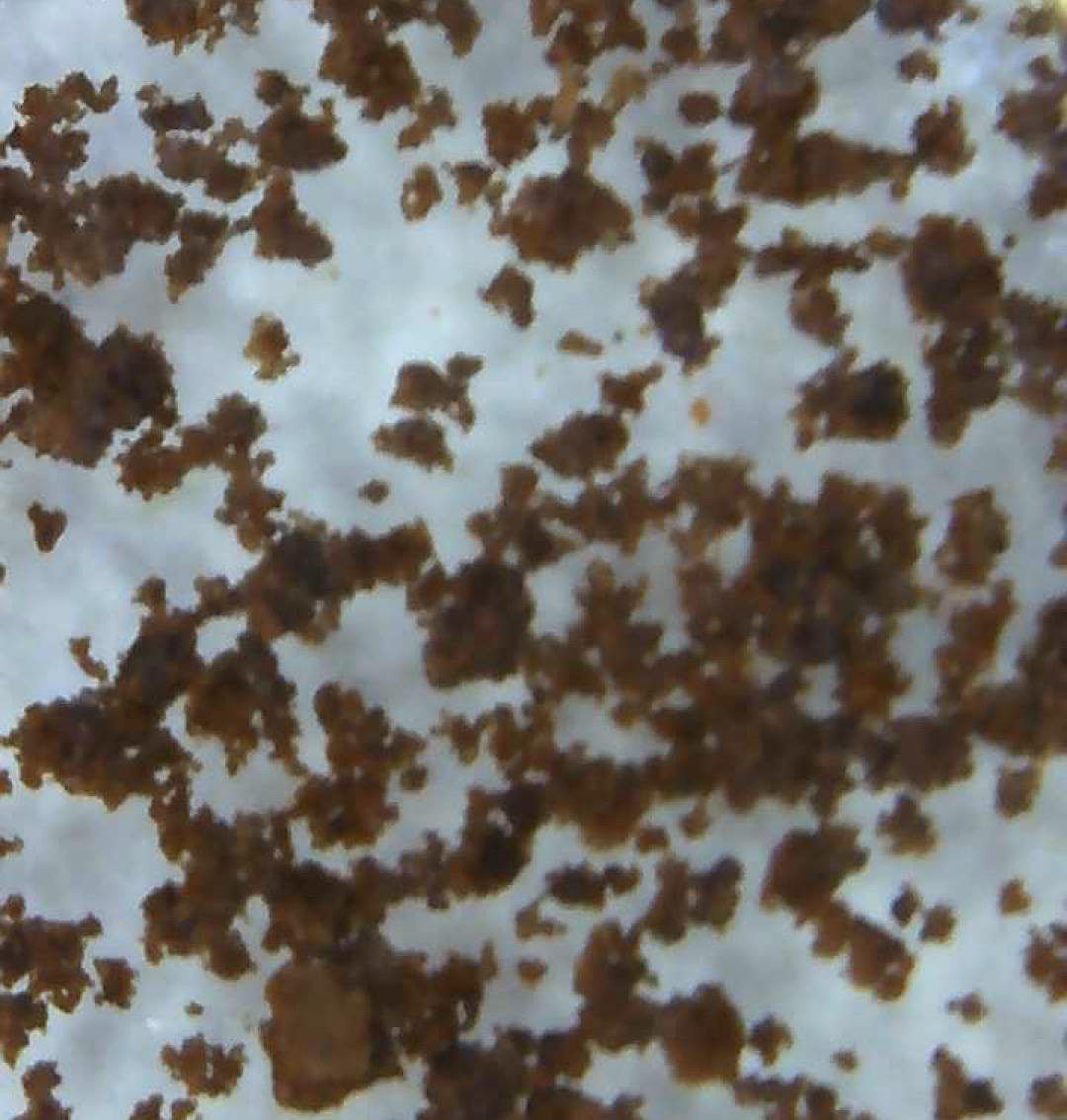

What I have clearly seen is that the only way to ensure the fine particle integrity in the powder is to consolidate it. If the powder is allowed to float freely within the grinder, even for a fraction of a second, the shot will be ruined. The fines will migrate in the slightest static environment because they are lighter, more easily pulled.

Here are examples of two dosing systems that solve this problem:

1) The Niche Zero

The Niche Zero offers a take on a standard Italian grinding chamber with two small ports that effectively consolidate the grounds, trapping the fines.

In the Niche Zero, we see a standard Italian dosing chamber with a sweeper arm that forces the ground coffee out of the two small exit ports. Being squeezed through the two small ports consolidates the powder, assuring 100% particle integrity.

Note that the grinding chamber is very small compared to most designs, so chambered coffee is only two grams, which is easily purged by the barista if the grinder sits for any length of time.

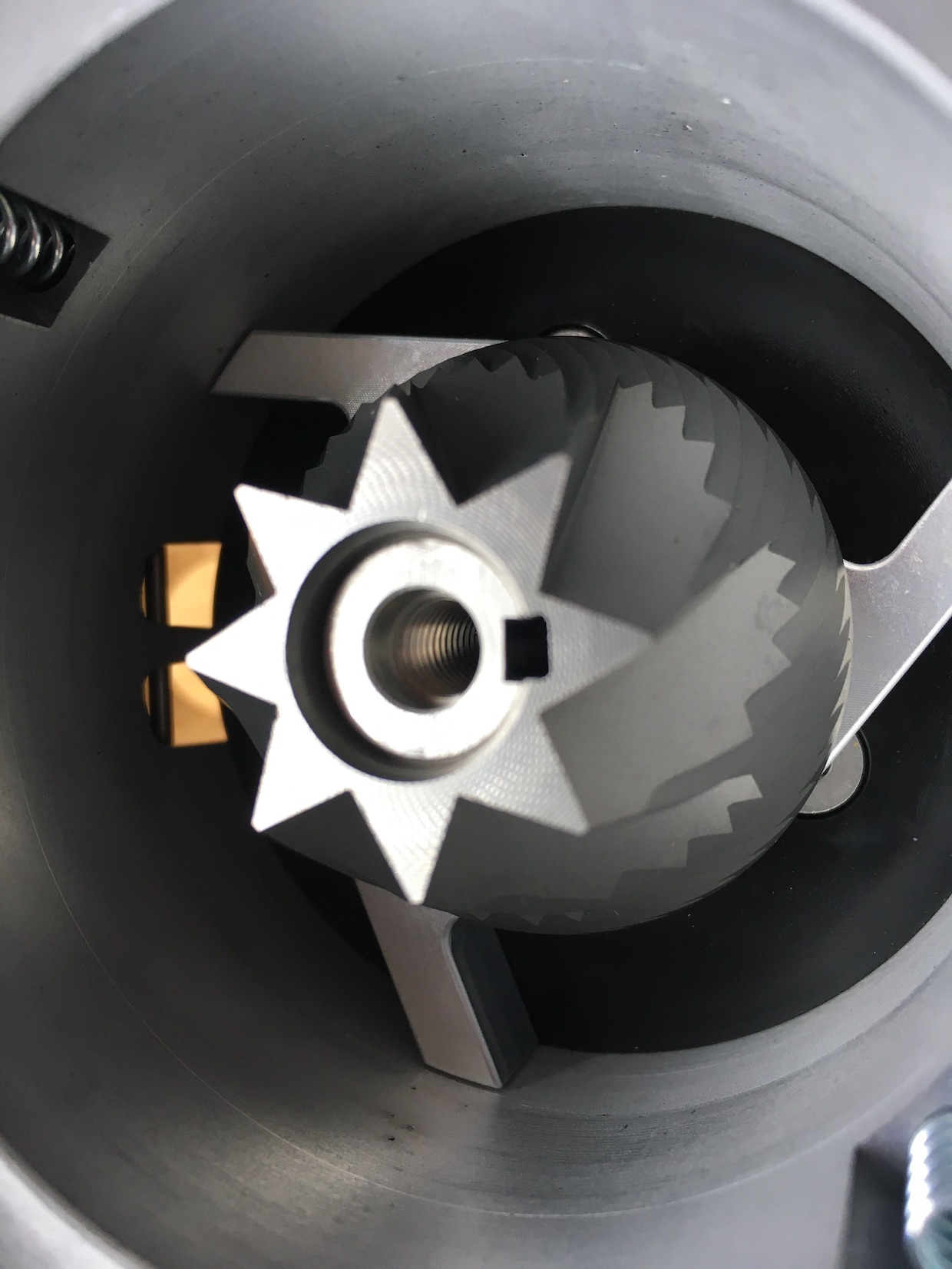

2) The Etzinger ramp impeller

The Etzinger ramp impeller, which in my opinion results in the best dosing system, includes two opposing impellers that impact the coffee instantly as it exits the burr set, trapping the fines and resulting in zero chambered ground coffee.

The spinning ramps crash into the grounds oozing out of the burr set, impelling them downward with sufficient force to consolidate the fines.

Ideally the coffee should dose directly into the portafilter, but this is messy and wasteful. At Vivace, we use a static-free cup to catch the ground coffee, with best results.

Heat control

The ground coffee should be at or below 100°F (38°C). Many, but not all, commercial grinders offer some sort of fan mechanism to keep coffee temperatures from becoming excessively high.

Grind by weight

An artisan barista is very concerned with the flow rate of the shot coming out of the machine. Dosage really affects this. The ideal grinder must be able to automatically shut off when a desired dosage weight has been achieved. An accuracy of +/- 0.2 grams is essential. Precision grind-by-weight is a feature not found on most commercial grinders.

A final call

Like the temperature barrier built into the machines by old-style thermostat controls and inadequate group head designs, our culinary art remains stuck until a perfect grinder is built.

Consider this an even louder call to action! Expert baristas that wrestle with inadequate grinders day in and day out need to speak up. Let the machine manufacturers know there is a market for the perfect commercial espresso grinder.

David Schomer

David Schomer is the co-owner and founder of Seattle’s Espresso Vivace.

He is the author of "ESPRESSO COFFEE: Professional Techniques” (1995) and recently published the 2022 edition of “ESPRESSO PERFECTION”. He created the video Caffe Latte Art in 1995, and an online seminar entitled "ESPRESSO PERFECTION, a companion to his latest book.

David’s temperature research with La Marzocco led to the adoption of PID controls throughout the espresso machine industry.

David has trained hundreds of baristi over his 35 year career at Vivace.

Comment

4 Comments

Comments are closed.

In my experience fines/coffee distribution and packing in the portafilter make a big difference even with the Niche Zero. This can come from the technique used to level the coffee (or not leveling it?!), tapping the portafilter too much, and tamping/WDT technique. I now have a simple workflow that avoids these issues and produces consistent extractions. Whether or not I prefer the Niche Zero or a flat burr like the Niche Duo largely depends upon the coffee and my preference for the day.

This has to be an April fools joke in August, right?

We’ll assume you are content with a Mr. Coffee machine from the 1980s.

How is this brilliant article a joke? Schomer has done more to advance the art of specialty coffee than anyone else working in the field. I’ve learned much from him over the last 28 years. All it takes is one visit to one of his Vivace cafes in Seattle to understand that he knows what he’s talking about. Even the worst shot from Vivace is 100 times better than any other shop on the West Coast (where most of the kids have no idea what they are doing, and most shop owners don’t realize how much they owe Schomer as they utilize his ideas day in and day out…

Something it bugging me: if fines particles integrity is so important, that means we should avoid any form of WDT right ? coz we essentially displace the fines moving them to the bottom (owing to the inverse segregation of granular convexion, aka the Brazil nut effect) by moving around with the needles, right ?

Also, the author doesn’t mention the idea of a water spray to prevent static, I am wondering why ? would that mean this technique actually doesn’t work ?