[Editor’s note: This is part one of a two-part column by guest author Andrew Hetzel. Jump to Part 2 here. Daily Coffee News does not engage in sponsored content of any kind, and all views or opinions expressed in this piece are those of the author/s.]

Agriculture is a leading cause of land use change and deforestation, and the second largest emitter of greenhouse gasses behind burning fossil fuels. To reduce the adverse effects of farming on the climate, the European Union passed landmark legislation in 2023 requiring seven agricultural commodities to be confirmed “deforestation free” before importation.

Enforcement of the European Union Deforestation-free Regulation (EUDR) begins in January 2025. Coffee, claimed to represent 7% of EU-driven deforestation, is one of the law’s regulated commodities.

While applauded as a significant environmental milestone, EUDR’s design fails to consider complex smallholder agricultural supply chains, such as those found in coffee. Coffee is farmed by millions of smallholders in the Global South, where rules prescribed by distant lawmakers may be incompatible with local production systems, or otherwise beyond the capabilities of disadvantaged farmers to implement.

People dependent on coffee farming for food security will face the most significant barriers. Smallholders will likely suffer lower demand and earnings if banned from the world’s largest coffee market, leading to unintended consequences.

This two-part article examines the challenges and possible outcomes of EUDR through the lens of Timor-Leste, one of the world’s youngest and poorest nations. The conclusions reached, however, may be directly applicable to other smallholder coffee farming regions, or to other smallholder-farmed regions producing different shade-grown crops.

Timor-Leste

“Timor Leste (orthographic projection)” by Alvaro1984 18 is licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Timor-Leste, formerly East Timor, is a small independent country established in 2002 that occupies the eastern half of the Island of Timor, on the eastern edge of the Indonesian archipelago. It was a Portuguese colony from the sixteenth century until 1975, then gained independence for nine days before Indonesia invaded. During the 25 years of Indonesian occupation that followed, 180,000 Timorese died from starvation and conflict, and over 80% of the country’s infrastructure was destroyed. Now a sovereign nation, Timor-Leste remains one of the world’s poorest countries — a UN-designated Least Developed Country where half or more Timorese live in extreme poverty.

Coffee in Timor-Leste

Coffee has been one of Timor-Leste’s most important cash crops since the Portuguese introduced it in the 1800s. Currently accounting for 90% or more of non-oil merchandise export value, coffee is a vital source of food security for 77,000 rural households and a primary source of income for 37% of the country’s population of 1.4 million.

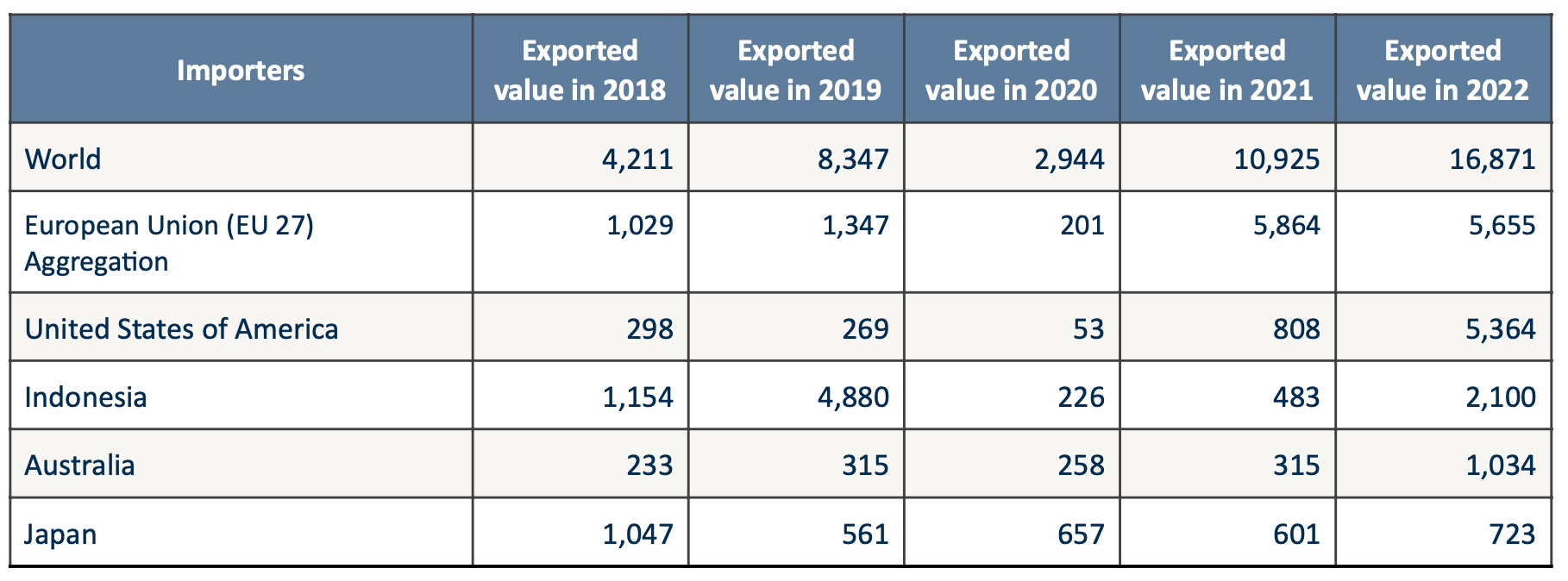

As a bloc, the European Union is the largest market for Timor-Leste coffee. In 2022, the EU was the destination for 33.5% of coffee exports by value, and more when considering transshipments through intermediary countries for other reasons, including decaffeination.

ITC Trademap Data, HS 09011 (coffee not roasted or decaffeinated). Export value from Timor-Leste in thousands of US dollars.

Thousands of semi-subsistence smallholder farmers produce Timor-Leste’s coffee as a forest crop shaded under continuous canopy. As coffee agriculture expert Tony Marsh observed in 2001, “Arabica coffee is grown under shade in East Timor, as it does not survive without shade in the harsh, dry conditions.”

Each household typically farms less than one hectare, which may be spread across multiple plots of land.

Once harvested, coffee cherries follow a complex path to market, subject to the location and capability of each producer, as well as any preexisting agreements. After arriving at the mill, coffees are comingled before processing, sorting and grading for export. Nearly all is exported as a cash crop, with a small fraction of production consumed locally.

Household income from coffee farming is typically less than US$250 annually, earned mainly during the harvest months of August and September. Farmers are more likely to suffer food insecurity outside harvest months, underscoring the importance of coffee as a cash crop. However, no better alternatives exist to generate rural income.

As one report on the Timor-Leste coffee sector noted, “Establishing alternative crops will involve major investment at all stages of the production and supply chain. This, however, is not currently feasible.

European Union Deforestation-free Regulation (EUDR)

EUDR entered into force on June 29, 2023. The law is intended “to guarantee that the products EU citizens consume do not contribute to deforestation or forest degradation worldwide.”

To accomplish this, EUDR regulates seven commodities linked to deforestation: cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, soy, wood and some derived products (i.e., roasted coffee). It requires that they be confirmed “deforestation-free,” as defined by the EU since 2020, before being allowed entry for legal sale in Europe.

Enforcement begins in January 2025 for large firms, with another six months allowed for smaller firms to comply. After that, businesses that sell products violating the law may be fined up to 4% of annual European turnover. This includes green coffee importers, roasters, and retailers who make coffee available for sale in Europe.

Why Coffee?

The seven regulated commodities were selected based on an association with deforestation and the EU share of global demand.

A demand study compared the historical net increase in deforestation for each country to the net increase in land use for producing a commodity over the same period. Results indicated a percentage of “embodied deforestation” for each. To illustrate, “if coffee was responsible for 5% land expansion, then 5% of the national deforestation would be attributed to the commodity.” Since the EU is the world’s largest market for coffee imports, approximately 30% by quantity, coffee rose to a level of high importance for regulation despite being less directly linked to deforestation than other commodities.

A rural village settlement, or suco, adjacent to coffee farmed area of Timor-Leste. Photo by Andrew Hetzel.

Curiously, soluble coffee is excluded from regulation. Soluble or instant coffee is typically produced from coffee of the Robusta species. Robusta is grown mainly in Southeast Asia and West Africa, which experienced among the highest rates of deforestation attributed to coffee in research supporting EUDR’s demand study.

EUDR Requirements

To comply with EUDR, businesses must perform due diligence and keep detailed records about the source of each regulated commodity, verifying that no deforestation has occurred within the production area since 2020. The cost of compliance and burden of proof is placed on operators who make goods available for sale in the EU.

Exporting countries will also be assigned a risk level for deforestation (low, medium, or high) by the EU, determining the degree of scrutiny given to its shipments. Notably, the level of risk is aggregated across commodities, so all commodities will be treated as high-risk drivers of deforestation from a country where any commodity is considered high risk.

Important details, such as the criteria used when assigning risk levels, have yet to be clarified by the EU, as of this writing.

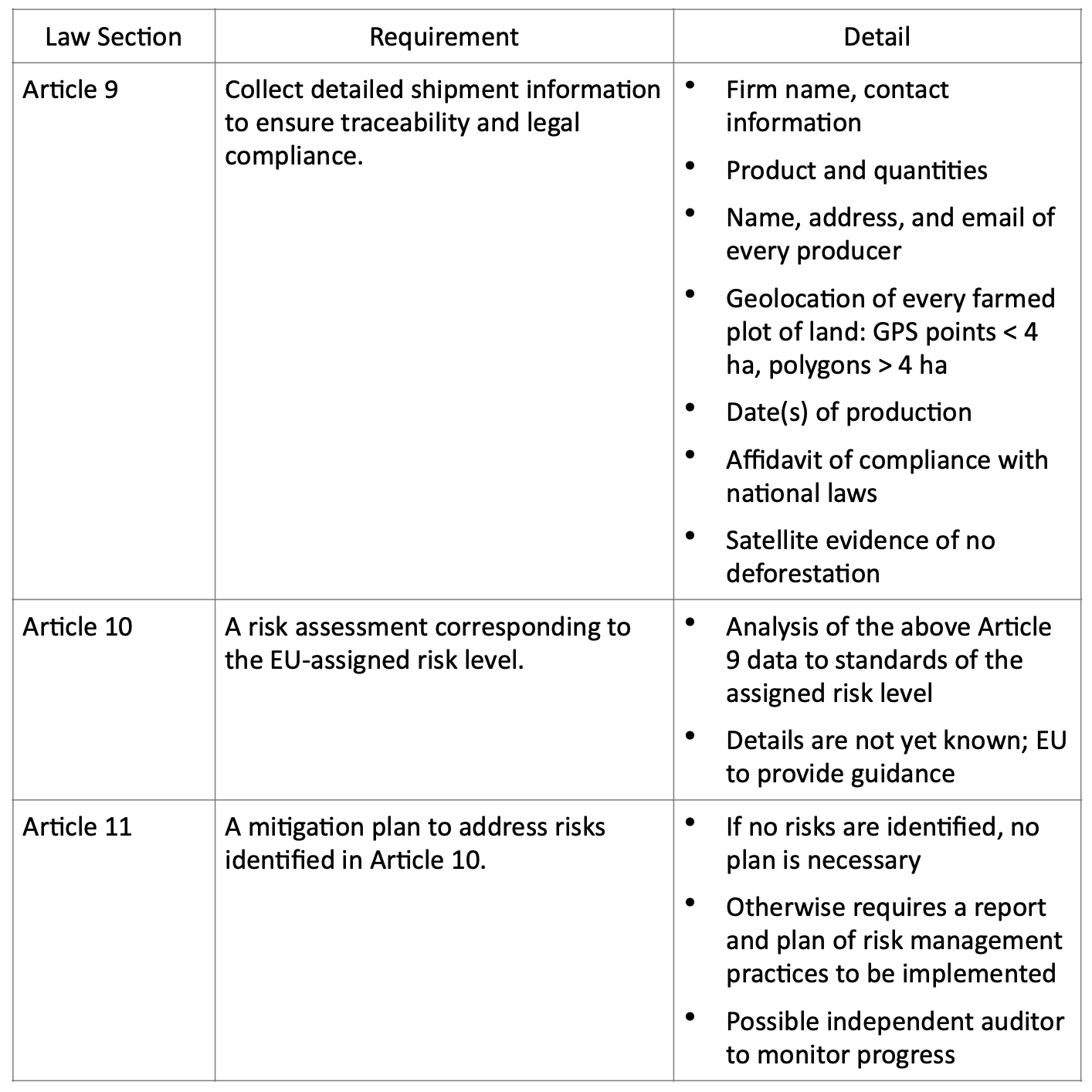

Specifically, EUDR imposes three new requirements on importers:

Understanding these requirements and the realities facing smallholder farmers in Timor-Leste are essential to understanding why compliance may be impossible for many. Stay tuned for Part 2 in this series, which will explore the real-world impacts the EUDR may have on smallholder farmers.

Read Part 2 of this story here.

Comments? Questions? News to share? Contact DCN’s editors here.

Andrew Hetzel

Andrew Hetzel is a coffee value chain consultant with 20 years of experience working in smallholder farming communities of Southeast Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. He is a contracted adviser and team leader for a multi-government-funded agroforestry rehabilitation program in Timor-Leste.

Comment