One of the most attention-grabbing stories to come out of this month’s SCAA Event was the weeklong journey — by foot, car, plane and boat — of a group of exporters escaping the escalating civil war that surrounded them in Yemen.

Their mission was to get approximately 100 kilos of Yemen’s finest green coffee to Seattle, part of a larger journey to reintroduce the country’s specialty-grade coffees to the world.

Exporters Andrew Nicholson (Rayyan Coffee), Mokhtar Alkhanshali (Mocha Mill) and Shabbir Al-Ezzi (Al-Ezzi Industries) all made their way to the United States through one way or another, and their journey was punctuated by what longtime industry consultant Andrew Hetzel says is likely “the most well-attended cupping event in SCAA history.”

“The show has been great,” says Nicholson, who launched Rayyan Mill near Sana’a three years ago after traveling through Yemen in search of coffees. “We came with this crazy story, and it kind of blew up on social media, so we said, ‘hey let’s go with it.’ “

The Seven-Day Journey

The “crazy story” involves the deadly conflict ongoing throughout Yemen. Nicholson and Alkhanshali were determined to reach Seattle, despite the escalating airstrikes surrounding them in Sana’a. They fled by car to the Port of Mokha (Mocha), a seven-hour drive. From there, they were told by boat captains that they were awaiting diesel shipments from Djibouti who kept saying, “It will be here tomorrow.”

Knowing that could mean a few days or more, Nicholson and Alkhanshali worked out a deal with a local fishing boat captain. “We told the authorities what we wanted to do,” says Nicholson. “They said ok, stamped us out and we got in the boat for about five hours from the port of Mokha in the Red Sea into Djibouti.”

By the time the travelers arrived in Djibouti, delivered by the Coast Guard after another five-hour drive for missing their entry point, they looked pretty rough. Says Nicholson, “I think the authorities were quite confused seeing some Americans looking so bad on a little fishing boat, so they had a few questions for us — for about a day and a half.”

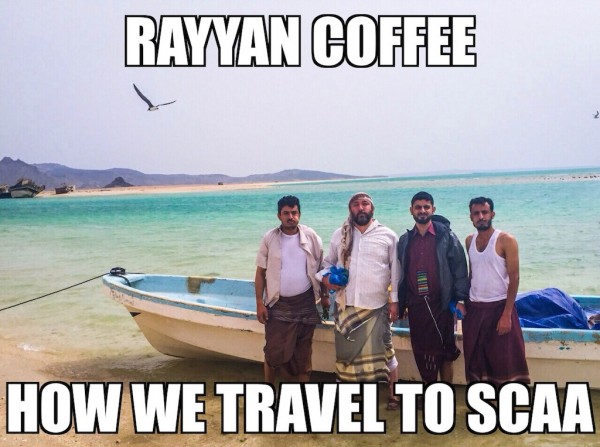

Nicholson’s cousin created these memes to capitalize on the media exposure leading to the SCAA Event. Nicholson is pictured middle left, while Alkhanshali, of Mocha Mill, is pictured middle right.

Eventually, with some help from the American Embassy and the approval of the Djibouti port authorities, the travelers hopped a 3 a.m. flight to Kenya, from which Alkhanshali flew to his hometown San Francisco and Nicholson flew to Dallas, where he was picked up by Sean Marshall of Houston’s Southside Espresso, driven to the Houston airport to catch a flight to Seattle on the eve of the SCAA show.

“By this time, I’m jet-lagged, I’m boat-lagged, I’m everything-lagged,” says Nicholson. “But I was just so happy to Skype with my Kids. Kids really like saying Djibouti, so my daughter gets a big kick out of that.”

The Journey of Yemen Coffee

A good point of entry, so to speak, the seven-day journey story is only a small chapter in a much larger story developing around Yemen coffees, and the Yemen agricultural sector as a whole.

USAID is currently in the midst of a $25 million program called CASH, a Feed the Future-financed program designed to create sustainable market systems, increase rural incomes, and enable poor residents to purchase the food necessary to meet their daily nutrition needs. Implementation of the program is managed by Land O’Lakes International Development, while coffee sector assistance is being provided by the Coffee Quality Institute (CQI).

Hetzel is CQI’s representative for the coffee program in Yemen, and he is in year one of the five-year project that includes Yemen coffee capacity building, quality improvement, and farmer training in the basic practices of cultivation and harvesting. The program also involves trade marketing, which explains his relationship with the Yemeni exporters.

The Yemen coffee industry — one of the world’s longest-running — is fascinating and complex, carrying with it many of the vestiges of ancient farming and processing practices. Coffee exports from Yemen have declined significantly in recent decades, with many individual family farmers switching to crops like khat (quat), the plant that is chewed locally as a stimulant. Much of the coffee currently produced in Yemen grown by individual families, purchased by middlemen, dried and stored as naturals for what is by industry standards an inordinate amount of time.

“One thing they do in Yemen that’s kind of interesting is they’ll store those coffees for a period of years in what are essentially caves,” says Hetzel. “Eventually, they’ll use the coffee as a form of currency. It’s not typical practice in the industry to store naturals for that extreme amount of time.”

Traditional milling in Yemen is done through a somewhat rudimentary process involving the grinding of stones. Hetzel describes it as like a large mortar and pestle system. Once milled, most Yemen naturals find their way to Saudi Arabia, where they are often mixed with lower-grade Ethiopia Harrar coffees.

New Yemen Coffee

A common goal among Hetzel, Nicholson, Alkhanshali, Al-Ezzi and others who are invested in Yemen coffee, either through the CASH program or private interests, is to separate Yemen specialty coffees — to recreate and develop markets for a cash crop that can be truly sustainable and support the sector and its individual farmers.

Doing this requires some combination of introducing modern farming and processing infrastructure and training methods, while adopting and expanding some of the ancient techniques that have made some Yemen coffees so naturally exotic over hundreds of years. (Incidentally, Texas A&M-based World Coffee Research and CQI are currently in the process of tracing the genetic makeup of numerous Yemeni heirloom arabicas.)

“This is a really broad initiative,” says Hetzel, “but we already seem to be seeing some results and some interest from the industry.”

If you were to graph that interest, you’d see a huge spike around the week of the SCAA event. On the Monday prior to the show, Al-Ezzi was in Washington D.C. as part of public cuppings at numerous La Colombe locations. The Philadelphia-based roaster is buying Yemen coffees as part of a pilot partnership project being led by USAID. On Saturday morning of the SCAA show, the Yemen coffee delegates held a breakfast where they shared some of the recent developments with a group of influential people representing the coffee buying side of industry. And a public cupping the day that followed saw some 120 to 130 tasters standing elbow-to-elbow for a place at the table.

“Yemen coffees used to be a mainstay of the specialty coffee scene, but in the past decade they’ve been a lot harder to find,” says Hetzel, who ran the hectic cupping. “It was really great to be able to introduce some of these people to younger people in specialty coffee, since they represent the future of the industry.”

A day following the SCAA cupping of his coffees and those of his colleagues working Yemen, Nicholson was still visibly emotional when discussing the renewed interest in the country and its coffees.

“We’ve been working so hard, not just for our company, but for Yemen coffee,” he says. “I had tears in my eyes looking at all the people there, and they were all such beautiful coffees on the tables. I just kept thinking about all the people who helped put them there.”

Of course, the putting of them there almost didn’t happen.

“You have to understand that since we started this company, I’ve seen tracer fire a few meters in front of me multiple times; we’ve had containers hijacked by bandits on the roads; there was a war in Sana’a when we started this mill,” says Nicholson. “But the important story isn’t how we got here. It’s that these coffees are getting the attention they deserve. That’s why I said on the boat, ‘If the Somali pirates get me, just make sure the coffee makes it to SCAA.’ ”

Nick Brown

Nick Brown is the editor of Daily Coffee News by Roast Magazine.

Comment