El Salvador and its coffee industry are both in a perilous state. Various NGOs, tech firms and forward-thinking producers are working to save the industry by addressing issues of environmental, financial and social sustainability, although the country’s coffee sector remains in a constant struggle to respond to natural forces such as leaf rust and economic forces such as the sagging commodities market.

“Buyers have to be aware that if they want quality, they have to do their part, and it’s not a buck twenty a pound,” Salvadoran coffee producer Jaime Alvarez told Daily Coffee News. Alvarez runs two farms in El Salvador, the 90-hectare El Cipres and the 45-hectare Colombia. “We need to de-commoditize coffee, [we need] relationship coffee… Our costs are going up. The costs of fertilizers never go down. They go up.”

Alvarez is considered a large producer in El Salvador, although his two farms ultimately pale in comparison to the much larger estate farms found in abundance in the world’s major producing countries such as Brazil or Colombia, and even elsewhere in Central America.

A History of Instability

The reason for this calls for some historical background. Most of El Salvador’s coffee estates were parceled out into smallholder properties as part of agrarian reform in the 1980s. To implement the reform, armed forces were often tasked with demarcating the new property lines, causing tension in the coffee fields that exacerbated other consequences of a bloody civil war, social injustice and economic disparity.

The civil war took more than 75,000 lives from 1979 to 1992. This led to a large Salvadoran population displaced and in search of asylum in the United States, particularly in Los Angeles, where many young people were unfortunately drawn into gang activity. Deported from the US after the FMLN and Salvadoran Government signed peace accords, it was this original displaced population that carried L.A. gang warfare back with it to El Salvador, where it has continued to wreak havoc in intervals over the past two decades despite numerous efforts by the Salvadoran government to end it.

Earlier this year, El Salvador’s newly-elected president Salvador Sanchez Ceren announced a more aggressive stance against gangs, to which the gangs responded with a wave of violence including a forced cessation of public transportation over this past summer, that involved setting fire to buses and killing bus drivers that resisted. According to reports by the BBC, the 2015 murder rate in El Salvador is on course to surpass that of 2009.

Alvarez, whose coffee farms produce a total of roughly 3,000 bags per year, notes that black market activity is more lucrative than coffee for younger Salvadorans these days. “The violence is affecting everybody, some areas more than others,” he said. “These kids find that by doing the wrong things, you get paid very well. The easy money comes quicker… It’s big business.”

From 2010 to 2013 alone, active coffee fields declined from 370,000 acres to 291,000 acres, with the high-water mark of the rust epidemic also arriving in 2013. According to a report from the ABECAFE Union for Mills and Exporters, 140,000 jobs were lost in the Salvadoran coffee sector from 2013 to 2014.

Making matters worse, on top of production woes in the fields and the current spike of violence, this year’s devastating El Niño has caused a crippling drought in the eastern portion of the country, damaging critical domestic crops such as corn and beans — staples of the Salvadoran diet. This means the nation will become more dependent on food imports from its largest trade partner, the United States.

In short, these climatic, economic and political factors have snowballed into a perfect storm of influence dissuading young Salvadorans from the pursuit of a life in coffee farming. Maren Barbee is the regional manager for Catholic Relief Services in the Blue Harvest water conservation project, operating in parts of Honduras, Nicaragua and El Salvador. She said she has seen increased coffee farming attrition in El Salvador, even if that means simply switching to other food crops. Said Barbee, “In the areas where we work, we found most farms extremely devastated by coffee rust, and practically abandoned or shifting to basic grains.”

Image courtesy of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) showing the projected effects ffects of El Niño around the world August 2015 to March 2016.

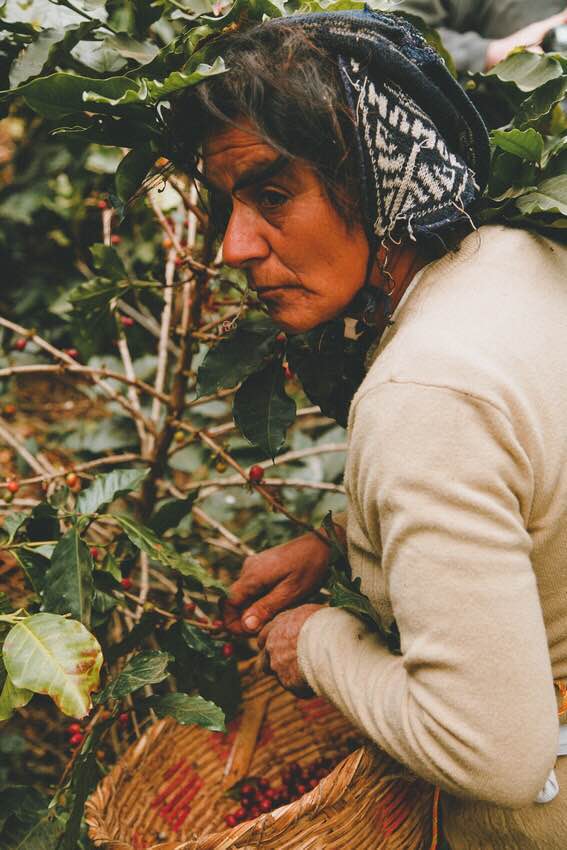

All this has led many forward-thinking people in El Salvador’s coffee sector to call for increased investment in all aspects of production, from widespread infrastructural reforms down to the individual farmworker treatment, where the country’s minimum daily wage for coffee harvesters is approximately $4 USD per day. In particular, Salvadoran coffee leaders are calling for increased specialty differentiation in order to free producers from the commodity chain.

“They live off a miserable salary,” Alvarez said of his farm’s workers, suggesting that attracting a steady workforce will require more than minimums. “We always pay above what the law requires, and we give them housing, energy, food like tortillas, cheese and beans, but that’s not enough, man.”

The Commodity Trap

Stanley Kuehn was in El Salvador on a USAID project at the tail end of the civil war, and he happens to be back now in this period of renewed turmoil. In the early ’90s, he was part of the group that first introduced USDA Organic certification to parts of El Salvador that were left to grow under passive conditions during the war. In many cases, guerrilla-run farms hadn’t seen pesticides or large scale production in more than a decade. In 2004, Kuehn was part of the group that brought the Cup of Excellence to El Salvador, further building the country’s reputation as a quality-capable origin.

Currently, Kuehn is the manager of the El Salvador Coffee Rehabilitation and Agricultural Diversification project, a USDA-funded program managed by the National Cooperative Business Association (NCBA CLUSA) that aims to improve production efficiency and access to financing for farmers of the beleaguered nation. Kuehn is tasked with spearheading the team that will help coffee producers to build business plans and capacity, as well as to diversify income streams by introducing short-term crops that can be sold in the off-season.

“The only future for El Salvador is to mainly stay focused on specialty coffee, which includes gourmet, Organic, Fair Trade, Rainforest Alliance,” Kuehn told Daily Coffee News. “Take all those and forget about trying to satisfy a generic coffee to the market.” He hopes to see more “direct-to-market” relationships to foster this transition to quality, effectively cutting out any middlemen that profit from usury and speculation.

Many at the management level of coffee in El Salvador have stressed a need to refocus the embattled nation’s resources towards specialty-grade production. To keep producers out of the commodity trap, NCBA CLUSA has organized meetings between trade associations to encourage support from banks and input providers.

“We’re bringing the sectors together to focus on what we project to be left in the country in the next 5-10 years. What we’re seeing is a lot of enthusiasm working together rather than working against each other,” said Kuehn. He added that 2016 will see a new cupping competition take place in absence of the Cup of Excellence. Somewhat different in focus, this competition aims to evaluate the quality of new varieties that have been propagated in El Salvador to gain ground against La Roya.

Government institutions such as the Salvadoran Coffee Council (CSC) and Centa-Cafe — the extension service provided through the Ministry of Agriculture (MAG) — are resources to the farmers, but many argue that government’s track record of assistance is less than exemplary.

This blog post on the Ministry of Ag’s site last month said the extension service managed by their Centa-Cafe office employs 85 people assisting around 7,000 Salvadoran farmers with bi-monthly visits and field training. The National Center for Agricultural Technology created this special division in July of 2014 after signing the National Coffee pact with ACAFESAL, the nation’s Coffee Farmers’ Association in February 2014, an agreement pledging to revitalize the Salvadoran coffee industry.

Sergio Ticas is the current president of ACAFESAL. He’s another in the loose cadre of professionals calling for both increased government assistance and a paradigm shift towards quality. In 2006, his farm located near the Honduran border won the Cup of Excellence, gaining $17 per pound which he then used to construct a wet mill. This year he expects production to fall by another 30 percent, despite early flowering that led to a nationwide uptick in yields in October. He believes technological assistance is necessary to prepare for rust and other negative effects of climate change.

“Climate change is affecting all of the coffee fields. We can’t fertilize for the lack of moisture in the soil, and as a result the trees are losing cherry, lacking nutrition and rain… We are the only producer country that doesn’t count on a research institution or technological aid,” Ticas told Daily Coffee News. “We do not receive a lot of credit. We are already very much in debt, and international prices are very low.”

Kuehn said much of the lending is handled at the processing level by cooperatives and exporting mills. Financing is disbursed to farmers before the harvest, then they deposit harvested coffee against their outstanding balance.

“It’s a simple system, but the banks won’t lend to the processors because there is no production in the field,” said Kuehn. “[Risk assessment] is based on the last four years of production average.”

Financial Leveraging

Because these realities present a fairly risky proposition for lending institutions, NCBA CLUSA will offer a guarantee fund to be used for leverage with the banks. Throughout the course of a four-year Coffee Stabilization program, proceeds from a portion of the U.S.-grown red wheat and soybean meal already entering the Salvadoran economy will be allocated to farmers and small producer organizations to implement the program’s objectives. These include farming cost reduction as well as performance-enhancing measures achieved through more organic, natural means. Kuehn hopes the Coffee Rehab program will be a departure from conventional practices such as copper-based fungicide and over-pruning, both of which damage the natural fertility of the soil.

Said Kuehn, “[NCBA CLUSA] is here to show producers how to use these systems, show them how to create their own on-farm inputs, organic inputs, bio-fertilizers, all of this to reduce the cost of production, so they don’t have to import fertilizers and synthetic pesticides that are going to contaminate the environment.”

CRS’ Blue Harvest project introduces biofertilizer as a healthy alternative to agrochemicals. Additionally, it implements on-farm renovation projects to curtail both soil erosion and agrochemical contamination of water source. “We work with over 2500 farmers in the three countries. 450 in El Salvador,” said Barbee. “We train and provide assistance in implementing best water and soil practices for agroforestry systems based in coffee. These practices include improving ground cover and canopy cover, water infiltration, reducing erosion through terracing, barriers, staggered planting along hillside contour lines.”

Beginning in 2014 and slated to run until 2016, Blue Harvest is a project with limited time and funding, but they have seen some success in raising awareness among smallholder farmers. “For our last mid-year report we found that about 85 percent of our farmers have started implementing water and soil conservation practices,” said Barbee, highlighting tree-grafting as a success, a natural fix that takes advantage of longer root systems for efficient feeding and erosion prevention.

Forward-thinking producers with more land and access to capital — which are less common, due in part to the 1980 agrarian reform — may also choose to enlist engineers to implement similar renovation projects in hopes of investing in the longevity of their farms. Alvarez notes that since hiring consultants for his Rainforest Alliance certified farms, his production doubled in one year, bouncing back from the rust losses of 2013.

Changes involved new irrigation techniques, while re-introducing traditional performance tricks such as the Agobio Parra style, a practice that anchors young tree tops to induce the proliferation of offshoots at a coffee tree’s base. Agobio is a virtually cost-free organic method being revived on farms across El Salvador, including Sergio Ticas’ own Finca Los Planes. “We’re focusing on those that have the passion,” said Kuehn. “We want to recapture their grandfathers’ agricultural practices in some cases, and improve techniques in others.”

Building Sustainable Business

With that in mind, the goal of sustainably-produced coffee in El Salvador is less about meeting market demands or satisfying the requirements of a label, and more about preserving the future of coffee there. Longevity requires sufficient investment. While many people across the specialty industry have some idea of methodologies involved in caring for a micro-lot from seed to cup, fewer of them know much about the cost, either financially or in terms of human hardship. With those factors in the dark, it becomes harder to assess the feasibility of the industry as a whole.

“It’s not just about focusing on the traceability of the coffee. It needs to be a traceable business,” said farm owner Alvarez. “We need to focus on specialty coffee. It’s a matter of integrating into the value chain, building strategic alliances between the roasters and producers.” To improve market access, NCBA CLUSA will collaborate with supply chain software providers GeoTraceability to measure the impact of their Coffee Stabilization program, and convey that information to potential lenders and buyers.

GeoTraceability aims to collect production data that can then be presented in a digestible, visual format to all interested parties. This month, their team is in San Salvador to tailor data reporting to the goals of the Coffee Stabilization program. “In the past we have implemented projects in Vietnam, Uganda. [These development projects] had no problem procuring financing, but there was no way to accurately measure impact,” GeoTraceability Business Development Manager Gerald Beaulieu told Daily Coffee News.

One hope is that the industry can put manageable numbers to what has long been known to be insufficient compensation. Better business practices could curb labor migration from the agricultural sector, a trend that has undoubtedly exacerbated black market activity in El Salvador. It might also cut down on immigration to the United States, which presents its own set of problems. “Coffee is not only a trade priority, it’s also an important part of our forests and employment, especially in the rural areas where you need it the most,” said Alvarez. “If we invest more in these areas there is going to be less emigration. The U.S. loves that. It’s probably cheaper to invest in the economy here than try to keep people out of the borders. Politically, it’s more sellable.”

While public investment within El Salvador has been scarce, there have been signs of effort on the government’s behalf. The Salvadoran Coffee Council will be assisting the production of an ad-hoc cupping competition next year in the absence of the Cup of Excellence program. Last spring, the Ministry of Agriculture disseminated 7 million coffee seedlings to farmers across the country. It’s unclear as to the progress of those in the drought-stricken east.

Until public investment begins to take root, however, the coffee industry of El Salvador lives and dies by the price per pound. The current confluence of crises facing the Central American nation could either be a clarion call or a swansong, as El Salvador’s coffee industry is subject to the capriciousness of the market and the whims of nature.

Jimmy Sherfey

Jimmy Sherfey is a freelance journalist and licensed Q-grader interested in specialty coffee production and the triple bottom line of sustainability. His blog, abeja.coffee, studies the ongoing struggle of good coffee and how strong, transparent relationships between producer and roaster can help. Find him at one of the many new, quality cafes of Orlando, Florida.

Comment