There are plenty of reasons to be concerned about the future of coffee: Changes in climate threaten farms across the globe; the commodities exchange market fails to adequately address the cost of production and, in many cases, the risk undertaken by the small farmer; coffee producer attrition to other crops and industries reduces the available workforce; and there are frequent, constant threats of disasters like earthquakes in Sumatra, rust fungus outbreaks in the Americas, or droughts in Africa and Brazil.

Without recognition, mitigation and adaptation, these issues and others can be destabilizing, negatively impacting the sustainability of our industry.

It’s also important to acknowledge that historically, our industry does not have a sterling record regarding human rights. Coffee cultivation was wielded as an imperialistic, colonial tool, and has a long, ugly history of slavery. Drive for the consumption of the commodity has spurred economic and political crises, established undemocratic elitism, and ignited war.

From an ethical perspective, coffee professionals and consumers have become more aware of our roles and potential responsibilities regarding these endemic problems. We’ve made some progress through development aid, education, research, collaboration and other avenues — though much room for improvement remains.

More disconcerting of late are certain external influences on coffee. We’ve seen a recent, dramatic shift in U.S. domestic and foreign policy that many people in the coffee sphere have found troubling, at best. Instability and uncertainty in the global macroeconomic picture is being compounded by ethical and legal concerns surrounding the orders of the new U.S. presidential administration.

In times like these, I find myself questioning my coffee career. Could I be doing more good for more people by abandoning my post and joining the Peace Corps, the press, or a not-for-profit advocacy group? Would our world be better served by fewer coffee professionals and more community organizers?

Undoubtedly, there are arguments to be made for abandoning the career of coffee service for a life of humanitarian service, and I’m not here to dissuade you from pursuing that path, should you so choose. But I do believe there is dignity in our craft, and that the coffee life has merit.

The history of coffee’s spread across the globe is not without humanitarian success stories. The advent of the coffeehouse both in the Arabian Peninsula, and later throughout Europe, stimulated philosophy and creativity, and fueled critical industrial and political revolutions. In more recent history, cafes in the 1960s were hubs of cultural revolution among poets and folk artists and activists, and in the early 2000s a movement called the Coffee Party arose, dedicated to “encouraging inclusive, civil, fact-based, solution-oriented dialogue — online and in public places such as coffee houses — in which we meet, talk, become informed and engaged as fellow Americans, rather than as members of political parties.”

Across cultures and history, the so-called third space — neither home nor work — of the coffee shop has been far more than a convenient place to drink a hot caffeinated beverage. It was and is a place of equality, and a welcoming environment for the enrichment of intellect, community and the arts.

It’s heartening to see that in politically charged times, even gargantuan coffee companies like Starbucks are unafraid to put forth strong statements supporting the work of social justice. My own employer, Royal Coffee, has joined with an unwavering voice and action by which I’m proud to stand. Many other coffee folks have dedicated time, energy, and funds to the cause. Among them, Blue Bottle Coffee founder James Freeman made a number of salient points in a blog post entitled “Coffee is a Muslim Crop,” about the company’s ACLU donations in the wake of the recent executive order regarding immigration and travel bans.

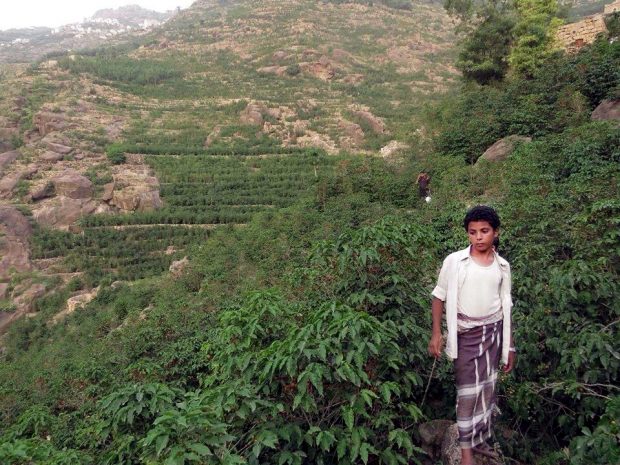

In fact, the first brewers, roasters, and growers of coffee were the Oromo people of Ethiopia, and they were Muslim. Yemeni members of the Islamic Sufi sect adopted the beverage as a part of their practices as early as 1470 AD, and commercial coffee cultivation took place exclusively in Yemen for the first century or more of its existence as a traded commodity.

Coffee swept across the Arabian peninsula and Egypt by 1500, and in the predominantly Islamic Ottoman empire, where major advances in coffee roasting and brewing took place, Judaism and Christianity also coexisted. In Europe, coffeehouses rapidly nullified class distinctions, progressing from a beverage exclusively available to the elite to one enjoyed by the masses. Coffee today is grown and consumed across an incredibly diverse population worldwide. Coffee farmers and drinkers alike are Latinos, Asians, Africans, Russians, Americans, Europeans, indigenous peoples, migrants and immigrants. Coffee is unequivocally multicultural.

Lately, coffeehouse culture has in certain respects gravitated away from one of chance meetings and the free exchange of revolutionary ideas. We now curate environments for business, arranged meetings, and/or crop-to-cup tasting experiences. There’s nothing inherently wrong with those goals, but the kinds of philosophical debates and cultural movements that once started in cafes are less possible in these environments we’re creating, in part because we don’t interact with strangers.

Freeman closes his post by stating a specific intent to engage a stranger in conversation the next time he’s inside a cafe — not necessarily about politics, but about the arts or culture or traffic or the weather, and he urges his readers to do the same. I, too, recognize that while the cafe has always been driven by consumption, there are less “distractions” now to consuming. We’d do well to remember that coffee is a cornerstone of the communal space that brings us together regardless of race, class, creed, or gender, and encourages open dialogue, a concept as relevant now as it ever has been.

Chris Kornman

Chris Kornman is a coffee romantic and educator, and a quality specialist with a history of indiscreet coffee buying, roaster fires, ill-advised travel, and oversharing. He is the author of Green Coffee: A Guide for Roasters and Buyers and regularly contributes coffee-related disquisitions to publications worldwide.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Years ago, as I first was irresistably drawn into the world of coffee (having absolutely HATED the drink for many decades) I came across a fascinating book on the used book shelf of a thrift store. It was the story of coffeehouses in the West, beginning in Vienna at the recovery from the Ottoman Turks back in fifteen something or another. The MOST FASCINATING section was on the coffeehouses of London, in particular, and England on the whole. “Penny Universities, they were, as the price of a cup (one pence) was one’s “tuition” to enter. Seating was rather close, typically, and the universal unspoken rule was anyone might sit anywhere, and is expected to converse and interact with whoever might happen to be near. A stevedore might sit next a nobleman, a farrier next an MP. Thus, over time, the London coffee houses became clearning houses and meeting places for all manner of people, ideas, needs, supplies.

In the shops of North America, sadly, most folk enter, pay their “tuition” (sadly far more than a penny) and find a seat… a solitary seat… and focus on…. their electronic devices. Interacting is, if anything, somewhere between taboo and not encouraged.

I have, on occasion, been able to strike up a conversation with strangers, and it has upon every occasion been engaging, delightful, at times challenging, stimulating, informative, humourous, in short, worthy of the “risk” every time.

I’ve also paricipated in the classic Ethiopian “coffee time”, and also found that to be an amazing experience…. time was shooed out of the room, the ONLY thing we had to do was to talk….. and drink the just roasted just brewed coffee. Time was no more….. we Yanks would do well to observe, and imitate, other cultures and how they value human interaction above electronic interaction.