Roast magazine has been awarded two 2017 Western Publishing Association (WPA) “Maggie” awards at the association’s annual awards banquet on April 28. A bi-monthly publication focused on the technical side of the specialty coffee industry, Roast received the award for Best Feature Article/Trade (circulation under 50,000) and Best Cover/Trade.

The WPA’s Maggie Awards, considered by many to be the most prestigious publishing prize in the West, have honored excellence in print and electronic publishing in 24 states west of the Mississippi River for 66 years.

The winner of the Best Feature Article, “Farmworkers in the Coffeelands,” was written by Michael Sheridan. The article took an in-depth look at the plight of coffee farmworkers — “the largest and most vulnerable group of participants in specialty coffee supply chains,” including millions of men, women and children — and exposed living and working conditions that at times “represent an affront to human dignity.”

The Best Cover winner, which features a captivating photo of a bee pollinating a coffee flower, was shot by Roast photographer Mark Shimahara.

Click here for a complete announcement from Roast.

This seems an appropriate time to revisit the award-winning feature penned by Sheridan and supported by photos by Oscar Leiva. At the time of publication, Sheridan was serving as the director of the Coffeelands Program at Catholic Relief Services (CRS). While he has since relocated to the United States to become the director of sustainability for Intelligentsia, many of the realities, practical considerations and strategies raised in the piece remain relevant today.

Below is the story in full.

Farmworkers in the Coffeelands

Improving Conditions for the Industry’s Most Vulnerable Players

by Michael Sheridan

photos by Oscar Leiva for Catholic Relief Services

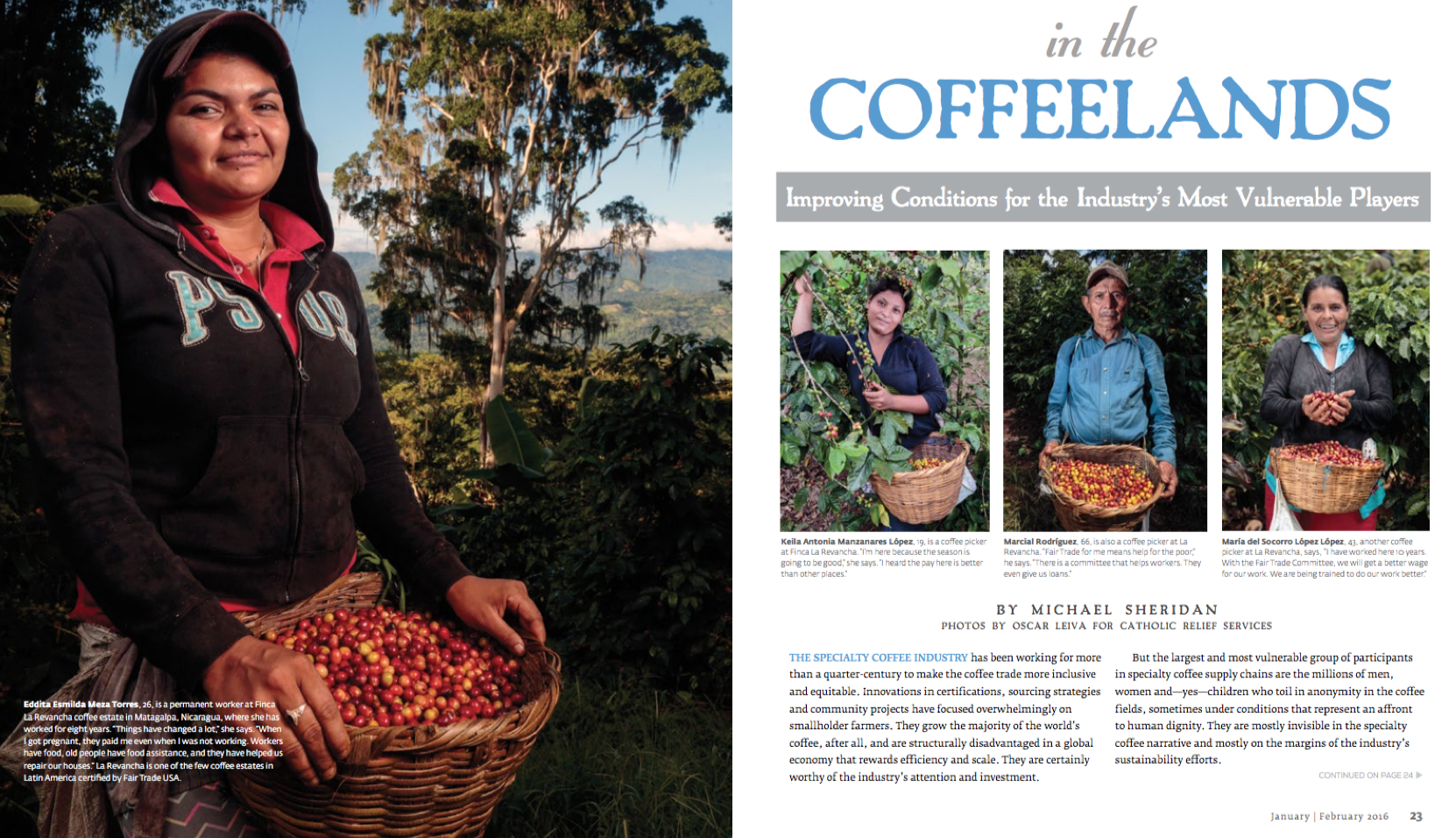

Eddita Esmilda Meza Torres, 26, is a permanent worker at Finca La Revancha coffee estate in Matagalpa, Nicaragua, where she has worked for eight years. “Things have changed a lot,” she says. “When I got pregnant, they paid me even when I was not working. Workers have food, old people have food assistance, and they have helped us repair our houses.” La Revancha is one of the few coffee estates in Latin America certified by Fair Trade USA.

The specialty coffee industry has been working for more than a quarter-century to make the coffee trade more inclusive and equitable. Innovations in certifications, sourcing strategies and community projects have focused overwhelmingly on smallholder farmers. They grow the majority of the world’s coffee, after all, and are structurally disadvantaged in a global economy that rewards efficiency and scale. They are certainly worthy of the industry’s attention and investment.

But the largest and most vulnerable group of participants in specialty coffee supply chains are the millions of men, women and—yes—children who toil in anonymity in the coffee fields, sometimes under conditions that represent an affront to human dignity. They are mostly invisible in the specialty coffee narrative and mostly on the margins of the industry’s sustainability efforts.

Marcial Rodríguez, 66, is a coffee picker at Finca La Revancha. “Fair Trade for me means help for the poor,” he says. “There is a committee that helps workers. They even give us loans.”

“This is an industry largely in denial,” says Erik Nicholson, a vice president at United Farm Workers (UFW), the iconic farmworker union started by César Chávez in California during the 1960s. The organization began working in coffee in 2012.

Nicholson has been impressed by the degree of industry engagement on origin issues.

“There is an awareness that things are not right at origin, and there has been a significant effort by many in the industry to reinvest,” he says. “I have not seen that in other commodities.”

He finds the industry’s record on labor less inspiring.

“The industry has been developed based on an assumption of unlimited access to cheap labor,” Nicholson continues. “As a result, you don’t have the kinds of investment in infrastructure or human capital that would make people want to keep working in the coffee fields year after year.”

In other words, you don’t see the kinds of investment in coffee farmworkers that you see in sustainability initiatives focused primarily on smallholder coffee growers.

Coffee cherry collected at La Revancha in Matagalpa, Nicaragua, is measured in wooden boxes to calculate how much workers are paid. Some of the hand-picked cherry falls during this process, which workers say makes them feel “robbed.”

Ben Corey-Moran, director of coffee supply at Fair Trade USA, puts it this way: “With a few exceptions on progressive and forward-thinking farms around the world, farmworkers in coffee are largely excluded from coffee’s promise. They do the work to produce great coffee, but receive very little of the value they help create. Their skills are essential, but nearly universally undervalued—we might even say exploited.”

At 5 a.m., workers at La Revancha gather for instructions on where to pick coffee during the harvest.

Who Are the Farmworkers in Specialty Supply Chains?

Quinn Kepes has conducted field research on farm labor in the coffee sector for Verité, a nonprofit that promotes workplace fairness and safety around the world. He characterizes farmworkers in the coffeelands of Latin America as “poor, rural, less educated, less connected, less informed, disempowered, accustomed to a traditional role of subjugation and dependent on a small range of employment opportunities, mostly under substandard conditions.”

Armando Castro Chavarría, 30, lifts about 200 coffee bags per day, each weighing approximately 120 pounds. He believes he is paid about 25 percent more at La Revancha than he would earn at other coffee estates.

But permanent labor arrangements are gradually disappearing in the coffeelands as farm owners embrace more flexible arrangements with temporary labor—a trend that mirrors movement in the global labor market toward outsourcing, subcontracting and other arm’s-length contracting mechanisms. “A flexible labor force is … lower risk and lower cost for farm owners,” Kepes says.

Temporary labor can be divided further into at least two subcategories: local and migrant labor. This last category—migrant farmworkers—is the most precarious.

Lionso Hernández, 45, has been working as a coffee picker at La Revancha for 10 years. “I am happy because the Fair Trade Committee of workers lends us money when we need it,” he says. “No one wants to lend money to agricultural workers.”

“The further workers migrate away from their home communities, the more vulnerable they become,” Kepes says, “and they become even more vulnerable if they cross international borders.”

Guatemalan migrants harvesting coffee in Mexico, for example, or Nicaraguans working in the coffee sector in Costa Rica may find that their legal status undermines their ability to access public assistance intended primarily or exclusively for citizens of the countries in which they are working.

What, When and Where?

Coffee farms hire labor in every coffee origin across Africa, Asia and the Americas. The farmworkers they hire do everything hands-on smallholders do, including seed propagation and nursery management, applying fertilizers and pesticides, weeding and pruning. But the biggest demand for farm labor in coffee unquestionably occurs during the harvest, one short window—or two, depending on the origin—every year when coffee needs to be picked at peak ripeness.

Prudencio Vidal López Gutiérrez, 50, is a temporary coffee picker at La Revancha. “I live nearby and I’m happy working here,” he says. “They pay us a higher wage and give us food. In other places you don’t get that.”

Farms of all sizes hire labor, not just the big ones. In fact, in countries like Brazil, demand for unskilled labor can be higher at midsize farms than at larger ones, where harvesting often is highly mechanized. The deeply rooted storyline about smallholder coffee farmers who depend exclusively on family labor may be romantic, but it is wrong.

More than three years into his engagement in the coffeelands of Latin America, Nicholson says, “I am still looking for those small producers who don’t hire labor, and I am having trouble finding them. Unless you are really, really, really, really small, you seem to hire somebody at some point.”

Elizabeth Granados, 33, is a member of the worker-led Fair Trade Committee at La Revancha. “Many mothers have received help,” she says. “They give us food for our children. We had a latrine project as well.”

What Does Farm Labor in the Coffee Sector Look Like?

“There’s a lot we need to learn about the specific challenges facing farmworkers,” says Corey-Moran. “From the research that’s been done to date, we know there’s some good, a lot of bad, and perhaps even more ugly.”

Research conducted by the nonprofit Catholic Relief Services (CRS) over the past two years on the conditions of farm labor in the coffee sector confirms this.

Throughout the Americas, large farms that rely on large numbers of workers sometimes outsource the entire labor function to brokers, from recruitment and transportation to oversight and lodging on the farm. The approach is efficient for farm owners, but unscrupulous labor brokers often promise would-be workers one set of wages and working conditions and deliver quite another.

They are part of a system of labor brokerage fraught with moral hazard. Farm owners pay a flat rate to brokers to manage the entire labor function. Because labor brokers take home everything they don’t spend, the system creates perverse incentives for paying workers less than the minimum wage and cutting corners on investment in lodging, sanitation and food.

Kepes sees exploitative brokers and unethical recruitment as two of the leading risk factors for farm labor. Verité’s research suggests that workers recruited by labor brokers are more likely to earn less than those hired directly by farm owners and are at greater risk of being victims of labor violations.

In one country, CRS conducted research into coffee farms that relied on labor brokers and were cited for labor violations. The results were not pretty. Access to clean drinking water was limited and living conditions were squalid: bedrooms with no beds, kitchens with no stoves, houses with no running water, and workers performing basic biological functions in forests and fields. There was also a range of restrictions on worker freedom, from the ostensibly innocuous, such as retention of identity documents, to the downright pernicious, including debt bondage and the threat of physical violence.

Debia Elena Arbizu Rivas (center), 24, and other women from Matagalpa on the coffee drying patios at La Providencia.

The U.S. Department of Labor’s List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor reports that coffee sectors in 14 countries rely on child labor, and this should come as no surprise. Coffee is an agricultural product. To hope that coffee—even specialty coffee—is somehow immune to the ills that ail other agricultural supply chains would be “wishful thinking,” according to Stephanie Daniels, senior director of agriculture and development at the nonprofit Sustainable Food Lab, which works to catalyze market-led innovations for sustainability in food systems.

“Agriculture is typically a low-margin business that is viable only when efficiency and sustainability are balanced and markets are stable,” she says. “For coffee plantations requiring hired labor, employers and employees are subject to the same dynamics as in any other agricultural sector.”

Standard Approaches

“Third-party verification and certification are largely the tools used to require suppliers to monitor and be in compliance with local labor laws,” says Daniels.

Three of the leading voluntary sustainability standards in specialty coffee—Fair Trade USA, Rainforest Alliance and UTZ Certified—include protections for farmworkers on coffee estates.

Rainforest Alliance certification is the oldest of the three. Like the others, it prohibits some practices—for example, child labor, forced labor and discrimination—and requires others, like paying minimum wage and providing workers with training, medical services, education, sanitation and decent housing, as well as access to personal protective equipment for handling agrochemicals. The organization introduced new requirements for housing and access to water in December 2015, and will release revised standards this spring intended to improve its labor criteria.

UTZ Certified got its start in coffee in Guatemala in 2001. From its inception, one of its “key aims was to improve the conditions of workers on coffee plantations,” says Business Development Advisor for the Americas Miguel Zamora. Today, UTZ Certified coffee farms worldwide employ nearly a quarter-million farmworkers who are protected by the UTZ Code of Conduct, which requires growers to comply with more than a dozen International Labor Organization conventions.

Fair Trade USA began certifying estates in 2012 because, according to Corey-Moran, “Coffee has a sustainability problem, and one of the main drivers of coffee’s unsustainability is a very unappealing value proposition to farmworkers.”

Fair Trade USA’s approach, which aims to enrich coffee’s value proposition for hired labor, is focused primarily on organizing farmworkers “so they can identify shared needs and create strategies to address them,” says Corey-Moran. “This organizing serves as a catalyst for dialogue between farmworkers and farm owners, relationship building, training, and the creation of shared value.”

These certifications, corporate codes of conduct and third-party audits can help companies identify and mitigate risks related to farm labor in their supply chains, but they are far from perfect. They tend to cover a broad range of performance indicators, including agronomic practices, natural resource management and conservation practices, and labor practices, without being optimized for any one set of indicators.

Even certifiers seem to recognize the limitations of certifications alone. That is why six voluntary sustainability standards, including Fairtrade International, Rainforest Alliance and UTZ Certified, are collaborating with the ISEAL Alliance as part of the Global Living Wage Coalition. The coalition is working toward a paradigm in which “remuneration received for a standard workweek by a worker in a particular place is sufficient to afford a decent standard of living for the worker and her or his family,” says Zamora.

Women work on the coffee drying patios of La Providencia coffee processing

facility, owned by Finca La Revancha.

Why Should the Coffee Industry Deepen Engagement With Farmworkers?

There is a good case to be made for specialty coffee to go beyond business as usual to engage more deeply with farmworkers and farm labor issues. Actually, there are four good cases.

- The Business Case

Labor shortages during harvest have become a perennial problem in some coffee origins, one that is likely to get worse before it gets better. As the economies in coffee-producing countries continue to develop and diversify, they will create more jobs that offer better pay and benefits to those who qualify than farm work in the coffee sector. Proactive engagement with farmworkers and measures designed to make coffee farm work more attractive will be vitally important to assure the continuous supply of coffee. Nicholson says the stabilization of labor supply is the starting point.

“Once you have a stable workforce, then you come into the sweet spot where you can start to have meaningful investment,” he says, including efforts to increase productivity and improve cup quality. Nicholson thinks of farmworkers in coffee as “field baristas” whose vital role in quality assurance historically has been underappreciated. Investing in farmworker training to improve quality is an investment that can generate hard returns for farm owners.

Daniels agrees.

“Farm labor is a major factor in an estate’s ability to deliver high-quality, highly productive coffee,” she says. “The people who directly tend the crops are those most responsible for quality and consistency. Without good working conditions, including training and proper remuneration, the full potential of a farm cannot be realized.”

- The Compliance Case

Coffee companies that don’t have a clear grasp on labor issues in their supply chains may want to start addressing that gap sooner rather than later, as lawmakers from California to Washington, D.C., and beyond are busy proposing and passing legislation to increase supply chain transparency—legislation that requires companies to report on their policies, practices and programs for identifying and addressing labor issues in their supply chains.

Keila Antonia Manzanares López, 19, is a co ee picker at Finca La Revancha. “I’m here because the season is going to be good,” she says.“I heard the pay here is better than other places.”

California Senate Bill 657—the California Supply Chains Transparency Act—requires companies doing business in California with more than $100 million in annual global revenues to make annual public disclosure of their efforts to identify and address risks of human trafficking and slavery in their supply chains. As of this writing, there is legislation in committee in both houses of the U.S. Congress that would impose similar requirements at the federal level: the Business Supply Chain Transparency on Trafficking and Slavery Act of 2015. The annual revenue threshold of $100 million per year is high, but these measures are a sign of the times: Today they may be binding only on the largest companies, but they promote a culture of supply chain transparency that is likely to influence the actions of the entire sector in the coming years.

- The Reputational Case

Many specialty coffee companies promote social responsibility as a core value, yet few go beyond certifications and third-party verifications to proactively mitigate latent reputational risks related to farm labor in their supply chains—risks that can arise even when suppliers are in compliance with local labor laws.

“Some countries’ legal frameworks are too weak and allow some practices that may be considered culturally acceptable even though they are forbidden by international agreements,” says Alex Morgan, director of market transformation at Rainforest Alliance.

In these countries, wages and/or working conditions could be considered scandalous by some U.S. consumers, even if they comply with local labor laws.

María del Socorro López López, 43, another co ee picker at La Revancha, says, “I have worked here 10 years. With the Fair Trade Committee, we will get a better wage for our work. We are being trained to do our work better.”

“I believe many U.S. consumers would be horrified to learn that the majority of workers we’ve encountered who are employed in coffee struggle on a daily basis to feed their families, and would question how such inequities are possible in an industry that produces such wealth for others,” says Nicholson.

- The Aspirational Case

Specialty coffee’s narrative has always been about differentiation. The concept of specialty coffee is firmly rooted in sensory differentiation, but that idea has been deeply entwined from the beginning with social differentiation.

In a 2014 issue of The Specialty Coffee Chronicle, published by the Specialty Coffee Association of America (SCAA), Peter Giuliano wrote, “Ethics are a prerequisite to specialness, and specialty coffee buyers must commit to working toward equity and prosperity throughout the supply chain at the same time as they work toward quality.”

Giuliano is a past president of the SCAA who currently directs its signature event, Re:Co Specialty Coffee Symposium. He is also a coffee history enthusiast, and he knows the history of labor in the coffee industry is complicated.

“Coffee was an important part of European colonialism in Indonesia, Africa and Latin America,” he says, “and labor abuse was a feature of colonialism. Many farms during the colonial period produced coffee by force or by intimidation of workers.”

Carlos Leiva, 22, is a co ee picker at Finca La Revancha in Matagalpa, Nicaragua. “Here I earn 20 córdobas (about 75 cents) more per basket than I would at other co ee estates,” he says.

Giuliano says that while “the best and the brightest farms in coffee today” respect the people who work there, “there are still plantations that maintain a colonial attitude toward labor. We can, and we must, finally put that dark tradition to rest if we seek to truly make good on the promise that coffee can be special.”

Taking Action

Steven Macatonia is director of coffee sourcing and ethical trade at Union Hand-Roasted Coffee in London. The company, which marries a relentless focus on cup quality with a tenacious commitment to ethical sourcing, is a member of the Ethical Trade Initiative (ETI), a cross-sector alliance of businesses, trade unions and nonprofits established in 1998 that drives improvements in working conditions in manufacturing and agriculture largely through the support it provides to member companies.

Macatonia was already a coffee professional when he made his first sourcing trip with an ETI social auditor.

“It was a farm I had been to several times before and thought I knew well,” he says.

ETI helped expand the breadth of his vision.

“Because of the perspective the social auditor brought,” Macatonia says, “I saw something I had never seen before: workers.”

Nearly 15 years later, the memory of his first encounter with seasonal labor still burns brightly in Macatonia’s mind: entire families of migrant workers sleeping side by side on rough-hewn wooden planks suspended unevenly just above the cold ground. There were no soft surfaces at all, he recalls. The latrines were barely better than open pits.

That visit opened a new dialogue on labor issues between Macatonia and the farm owner.

“It took some time, but helping him to understand what we saw as problems enabled us to work gradually through a process that effected real change,” Macatonia says. “Over a number of seasons, we could see the result of the good prices we were paying for the coffee, benefits in terms of reinvestment in improving living conditions for the workers.”

It doesn’t always go so smoothly. In some cases, Union Hand-Roasted has severed ties with valued suppliers over their refusal to dialogue on labor issues. The company also faces challenges at the other end of the supply chain.

“I have to stand in front of customers who are always trying to knock the price down,” Macatonia says. “It frustrates me. If you want to pay a living wage for workers, then yes, the cost of the coffee is going to a bit higher.”

Cost is a critical factor in the equation. Farm labor already represents a significant proportion of production costs on farms that hire labor. In many cases, it is the single biggest cost. Improvements in wages and working conditions will cost growers more, and those are costs that will need to be recovered in the marketplace.

Martiniano Hernández Álvarez, 70, another coffee picker at La Revancha, says, “I have worked four years here and I am part of the Fair Trade Committee. I am happy because we receive a bonus for our work. Some of this bonus is invested in social works for the community.”

Rainforest Alliance works to address labor concerns in “ways that are efficient and affordable and can contribute to higher farm income,” says Morgan. “The link to the market is key, and becoming certified has been an effective incentive for farms to improve their labor conditions.”

Cost is also top of mind for Darrin Daniel, director of sourcing at Allegro Coffee Company, based in Thornton, Colorado, as the company commits to “dive a little deeper on issues of farm labor,” as he puts it.

“What keeps resonating is that it is really about what is fair in terms of cost,” Daniel says. “It is about finding a place in terms of the price we pay that creates profitability for farmers and creates opportunity for improvements in labor conditions. We understand that means we might have to do more in terms of price premiums.”

Allegro, which sources coffee for Whole Foods Market and its own growing chain of Allegro Coffee Roasters locations, became the first U.S. roaster to sign on to a pioneering labor project at Finca La Revancha, a Fair Trade USA-certified coffee estate in Matagalpa, Nicaragua. The farm has been working with allies in the marketplace over the past five years to transform the relationship between management and labor through a process of farmworker organization and empowerment.

As part of the Fair Trade USA certification process, workers created a Fair Trade Committee comprised of permanent farmworkers elected by their peers. They engage in open dialogue with farm management and ownership about issues related to wages, working conditions, and the social needs of workers.

In 2014, Finca La Revancha began working with UFW on an ambitious plan to increase worker earnings by 50 percent over five years. Allegro is part of the effort, and agreed to a fixed-price contract with La Revancha for the 2014–15 crop year at $2.50 per pound. That covers the cost of production, earmarks 40 cents per pound for increases in worker wages, and sets aside another 20 cents per pound for farm ownership to reinvest in worker training and improvements to coffee quality that can increase per-pound prices further.

“This is not charity,” Nicholson says. “This model is predicated on workers creating more value by virtue of the responsibilities they are assuming and the idea that their compensation should reflect that added value.”

The First Step Is Engagement

For both Union Hand-Roasted and Allegro, taking action began with the simple commitment to engage proactively with labor issues in their supply chains—to ask questions they hadn’t asked before. In Macatonia’s case, that involved working with an ETI social auditor to expand his vision and vocabulary at origin. For Daniel, it meant expanding the questionnaire Allegro uses during sourcing visits to include issues related to farm labor.

“Unless you have engagement with suppliers at the ground level, you can’t understand what worker concerns are, what grower concerns are, or identify breakthrough solutions,” says Kepes.

Engagement alone will not drive change on the farm, but it is a necessary precondition for change. The measures Union Hand-Roasted and Allegro are taking to improve wages and working conditions in their supply chains would not have emerged without intentional engagement. Buyers who are disengaged, or do not communicate their concern regarding farm labor issues to supply chain partners explicitly, send a signal that farmworkers are not a priority in the marketplace.

SCAA Director of Sustainability Kim Elena Ionescu sees real opportunity in deeper industry engagement on labor issues.

“Coffee has a proud history of leadership around global sustainability challenges, and this issue presents us with another opportunity to set the bar higher for agriculture of all sorts, everywhere,” she says.

Industry leaders may resist engagement based on the complexity and enormity of the task, but Ionescu argues they shouldn’t.

“I don’t think being a leader means we have to solve these problems,” she says, “but rather to acknowledge them and work on them with the goal of benefitting everyone in the value chain.”

Nick Brown

Nick Brown is the editor of Daily Coffee News by Roast Magazine.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Conngrats! Great to see that this topic was the one that helped winning the award. We have come a long way on our collective knowledge of this issue as an industry. In part because of articles like this one. I hope we can see more on this in the future. Thanks