Edgar Fernández of Bloom Tostadores biking in the San Isidro district. Photo courtesy of Alexis Montes.

A mix of fog and car exhaust blankets the roads to the Barrios Altos district near the center of Peru’s capital city Lima.

Rusted trucks wobble through the traffic, dropping off that day’s commercial goods. Through the haze, pedaling a yellow custom-built bicycle laden with 70 kilos of coffee beans, 29-year-old Edgar Fernández weaves nimbly through the streets.

Fernández is the founder of the small specialty coffee roasting company Bloom Tostadores. As the roaster, barista trainer, sales director and overall coffee director behind the business, Fernández typically participates in nearly every step of coffee’s transformation from post-harvest production to direct delivery to customers.

Yet this one-person model has been severely tested by the COVID-19 pandemic in a part of the world that has suffered severe infection rates and is among the highest in the world in COVID-19 deaths per capita.

The Peruvian government, meanwhile, has extended one of the world’s most stringent quarantines indefinitely, limiting the movement of people and vehicles.

“Personal and private cars were not allowed on the roads,” said Fernández, noting that carrying raw materials by bike from a warehouse in Barrios Altos carries its own risks for crime. “You have to be careful so you won’t get robbed.”

For Fernández, the best course is perseverance: “Today, I’ll pedal and roast,” he said.

Working from home

Nearly the whole ground floor of Fernández’s home is a laboratory for coffee. As the front door opens, the familiar coffee smell greets you. Sacks of unroasted coffee sit in a corner a few meters away from the roasting machine.

Inside the workshop, a short stack of books sits next to manual brewing apparatuses, including titles such as Dear Coffee Buyer and The World Atlas of Coffee. To the right is another small space filled with gadgets; cupping bowls sit on top of a multi-tiered table that spins like a lazy susan; a vintage Italian Faema espresso machine stands at the ready.

“How about some music?” Fernández asked me on a recent visit. “I like to listen to rhythmic songs while I work. It keeps me going.”

“Summertime Madness” by Kool & the Gang starts playing as Fernández cleans the table from that morning’s rounds. In the background, a service bell rings, and the clamor of a muffled kitchen resonates nearby. The back door opens directly to a restaurant kitchen, a brief reminder that the outside still exists.

“When the pandemic started, I didn’t get out of bed for a week,” said Fernández as he wiped down the tables.

Coffees from Bloom featuring photos of the farmers who produced them. Photo by of Manuel Sanchez-Palacios

Persevering during the pandemic was difficult at first. Fernández had to start using social media to promote his coffee. With some help from friends, Fernández began to strategically promote different coffee varieties, focusing on the producers and origins for both coffee enthusiasts and casual drinkers alike.

Luckily, Fernández received a relatively large shipment of green beans just before lockdowns began, creating an advantage in those early months.

COVID-19 and Peru’s unpredictable political climate

Many of the hills Fernández has climbed during the pandemic weren’t physical; rather, they have been steep logistical climbs with police and military checkpoints. Peru’s first quarantine started on March 15 and continues today with curfews, checkpoints and mandatory indoor and outdoor mask mandates. Naturally, businesses have suffered.

When Peru had three Presidents in the span of one week last November, the country’s morale dipped, and so too did Bloom’s coffee sales.

“I had no deliveries for a week,” said Fernández, “and after elections on June 6, nobody ordered coffee for two weeks.”

Out of the many hurdles Fernández has faced so far, picking up and delivering coffee is what changed the most. He now uses two bikes. The yellow custom bike does the heavy lifting, carrying large sacks of coffee from the center of Lima, while his black fixed-gear delivery bike handles the small deliveries of roasted beans.

In the Peruvian Andes, Coffea Arabica feels the pandemic

The defense mechanism for coffee plants against pests comes from caffeine and acid lactones. Coincidentally, coffee bitterness comes from these two compounds. Said Fernández, “The more stressed the Coffea plant is, the more of these bitter compounds it will produce, including caffeine.”

When the pandemic reached the farthest corners of Peru, coffee farms felt the stress, too. Shaded between banana trees, high in the hills of Cajamarca, Coffea Arabica experienced a different kind of harvest last year. Masked workers picked the fresh cherries from Arabica trees, yet there weren’t as many workers available, and sometimes cherries were left overripe.

Small-scale farms, such as the ones Fernández regularly sources his green coffee from, struggled not only to harvest coffee; shipping and transport were also hampered by the pandemic.

Fernández’s post-pandemic caffeine dream

It was only five years ago that Edgar Fernández tasted his first cup of specialty coffee. He was hooked. Shortly after, he visited a commercial farm and started learning about the processes that lead to such cups.

“I walked a little down the dirt road from the commercial coffee finca and discovered a family-run specialty coffee grower,” said Fernández, who was fascinated by the difference in quality and practices used for specialty coffee. That’s when he decided to start his own coffee company, to help promote small growers and the fruits of their labor.

As a company run entirely by one person, Bloom flourished during the pandemic. In June 2020, Fernández roasted 256 kilos of coffee. However, as restrictions have slowly lifted this June, demand has dipped. Fernández roasted 64 Kilos less this June compared to last year.

While Fernández continues to seek out some of the best Peruvian coffees he can find, the goal is not to hoard it for himself.

“The connections that coffee creates is why I love this business,” said Fernández. “One day, I would love to open a large-scale specialty roaster with a coffee shop and offices… I want to share Peru’s coffee, but for that I would need some extra help.”

While heating water to 92°C, Fernández grinds 15 grams of a single-origin bourbon-variety coffee. He wets a paper filter in near slow-motion with boiling water and follows this with the fresh grounds he just measured. With a quick pour of his goose-necked kettle, Fernández evenly wets the grounds, initiating the bloom phase.

Said Fernández, “Let’s talk about this some more over coffee.”

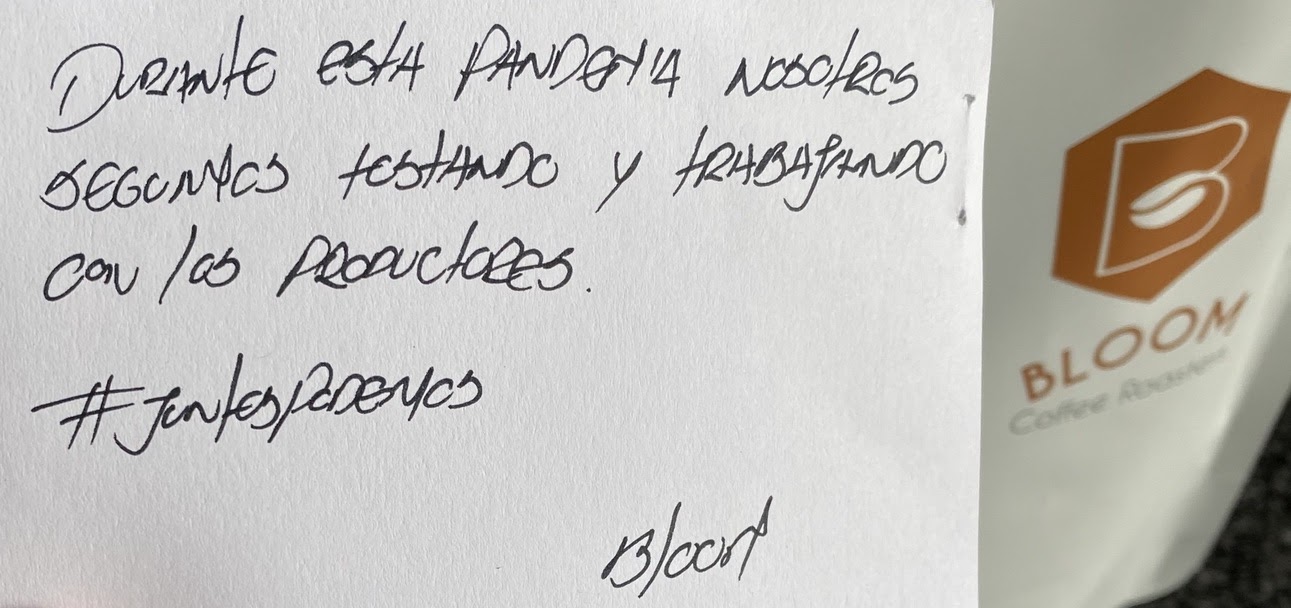

Behind one of the pictures, a note said, “During this pandemic, we will keep roasting and working with our producers #togetherwecan -Bloom” Photo by of Manuel Sanchez-Palacios.

Manuel Sanchez-Palacios

Manuel Sanchez-Palacios is a Journalism student at Harvard Extension. He moved to Lima in January of 2020 after graduating from UC Santa Barbara and is now earning his Masters remotely.

Comment