At the complex intersection of international development work and supply sustainability, few people in the global coffee industry can rival the power of forward thinking demonstrated by Peter Kettler.

With years on the business end of coffee — from humble beginnings as a barista in Paris through roasting, ownership, and green coffee trading and sourcing — Kettler has more recently dived deeper into development work at origin through his 11-year-old nonprofit Radio Lifeline (formerly called Coffee Lifeline before Kettler realized the potential the group’s projects could have on other agricultural supply chains).

Winner of the Specialty Coffee Association’s 2010 Sustainability Award, Radio Lifeline has been refining and growing a radio broadcast network — providing simple, solar-powered radios to farmers in Rwanda and now several coffee-producing countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Though its local broadcasts, the network conveys information from numerous stakeholders on agronomy practices, cooperative development and sustainability issues such as climate change adaptation. Broadcasts also cover topics essential to the livelihoods of these farmers, such as early childhood and maternal health, HIV/AIDS education, nutrition, food security, economic diversification and financial literacy, to name a few.

A goal of the radio project is to provide educational, rather than merely instructional, communications that are locally appropriate and accessible to farmers. The project also achieves economic viability and scalability, both of which are wonderfully reflected in Radio Lifeline’s most recent initiative, the Black Earth Project.

The Astounding Potential of Biochar

The Black Earth Project surrounds the use of biochar in multiple applications at origin. Kettler, among others leading the biochar charge in their respective agriculture fields, believes it has the potential for widespread improvements in waste management, dramatic increases in yields and additional revenue streams for farmers — all with relatively simple technology and minimal investment.

For the uninitiated, biochar is essentially charcoal created for specific purposes, such as soil amendment, water filtration or cooking fuel. Its production involves pyrolysis, the high-temperature burning of any biomass, such dried manure, pruned wood, corn stalks — the list is virtually limitless. In recent years, some leading environmentalists have been championing biochar for its carbon sequestration ability — a solution to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, improve water quality through carbon filtration, and as an amendment to increase soil fertility, particularly in low-pH soils.

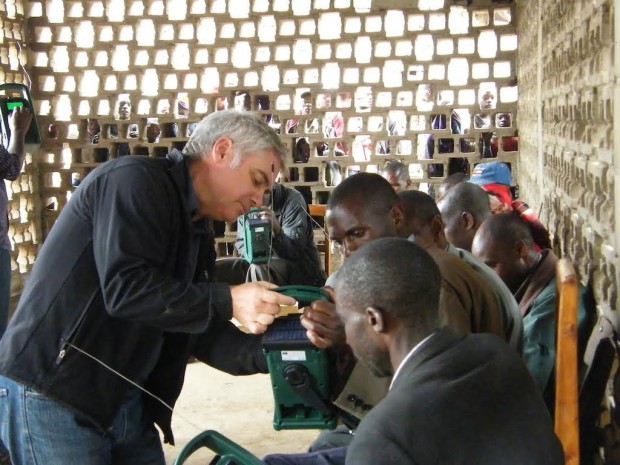

Introducing biochar to coffee farmers after an initial burn. This biochar was produced with dried maize stalks.

Despite its obvious upsides, the application of biochar in coffee farming has largely only existed on a hypothetical level. Until now.

Radio Lifeline has just received the initial test results from 18 test plots associated with six different coffee farms and cooperatives in Rwanda. Despite the relatively small sample size of the cooperatives that have reported yields — only 66 trees in total — the results are astounding.

“We now have results from four of the cooperatives, and what we found is that after adjusting for statistical anomalies — one them was off the charts, it was five times an increase in yield so I had to discount that — we got an average of a 33 percent increase in yield just after the first year,” Kettler recently told Daily Coffee News. “And what we’ve learned about biochar in other studies in other supply chains is that those yields continue to grow each year because all of a sudden, plants are feeding off of microorganisms in the soil, versus nutrients that are being applied through chemical fertilizers.”

Kettler noted that while there is a yield ceiling associated with biochar, its application is a one-time thing. “No doubt there’s going to be a threshold, but the flip side is that you only have to apply biochar to your field once,” Kettler said. “It will last for hundreds, some people say thousands, of years.”

Kettler does offer a few caveats regarding biochar as a soil amendment. It is not necessarily a replacement for fertilizers, although it naturally compounds the effects of fertilizers. Improvements in yield will vary by soil type, so results on trees in unkempt sandy soil in Rwanda may not be the same with well-maintained soil in, say, Costa Rica. Finally, the process to create biochar is somewhat labor-intensive, requiring the transportation, manual or otherwise, of the various feedstocks to be converted.

“I would hesitate to say that whenever you institute a new biochar project, in the first year you’re going to see a 33 percent increase in yield. I’d caution against that,” Kettler said. “I would say there’s going to be a benefit in soil no matter what you do, and there’s also going to be a decrease in input costs.”

A Closed Loop

Let’s forget yield for a moment. Two arguably more important applications of biochar in coffee farming relate to wastewater filtration and reductions to waste streams, issues at the front lines of coffee sustainability. Radio Lifeline has done some initial testing of systems designed to convert coffee mucilage into feedstock for biochar production.

“Water is a huge issue right now,” Kettler says. “That feedstock [from mucilage] would then become activated charcoal, and that charcoal would then filter the wastewater. We’ve had some very early trials and were successful in removing 90 percent of the effluence. Research is one thing, but scaling up and making it available and economically viable around the world is another thing.”

Kettler envisions biochar production systems that could be located at coffee mills, the ground zeros of coffee waste. Mucilage not otherwise used for composting would be readily available, and biochar would be more readily available for wastewater streams — plus, the mill is an ideal central processing location that could serve as a biochar education center for farmers. Considering biochar also as a potential revenue source for farmers through the production of charcoal briquettes, such systems could provide a kind of environmental and economic “closed loop” that could benefit players throughout the supply chain.

“Through a very simple application using one waste stream product to address another significant waste stream, we can have a closed loop that’s all taken care of once the initial education and equipment gets there,” Kettler said. “And it’s all very simple. It is equipment and raw materials that are already present. We’re not talking about shipping all this equipment to producing countries. They have plastic, PVC piping that can be converted into filter systems with biochar sand and gravel.”

The biochar production systems used in the initial field tests in Rwanda have involved the reuse of 55-gallon drums with the addition of screens, a solution Kettler said has costed “$40 or $50 a crack.”

Could Biochar Heat Up?

While the technology used to create biochar in the Rwanda field tests was rudimentary, Kettler suggests it nonetheless demonstrates immense potential for scalability. But scaling up, like any growth, requires funding, something that Kettler has had to devote increased attention to finding as the initial Black Earth project is soon to run its course.

Radio Lifeline will be partnering with Texas A&M-based World Coffee Research beginning later this year for some extended field research involving the application of biochar to some 800 trees in Rwanda. That partnership is likely to result in a much more robust set of data, something needed to begin to answer some of biochar’s existing unknowns in coffee, such as what are the ideal application levels to increase yield without damaging root systems, and if and how biochar may affect coffee flavor. Said Kettler, “That’s the next step.”

“WCR has a lot of bandwidth in the coffee industry,” Kettler said. “Their embrace of this technology and this approach could do a lot in terms of understanding what is available to farmers outside of simply ripping up plants and replacing them with some new hybrid. I think that working with soil fertility and the health of plants in existing plantations and farms is probably a less invasive approach.”

Again, yield and productivity is one thing, but Kettler also hopes Radio Lifeline’s biochar initiatives can continue to work toward that “closed loop” involving economic sustainability for coffee farmers and environmental sustainability through the mitigation of coffee waste.

“You’ve got the economic benefit of increased yield and lower input costs, then you’ve got the environmental impact, which is decreasing deforestation and improved groundwater because you’re putting a lot less chemicals into the ground,” Kettler says. “In terms of water filtration, if that project can get some momentum and get some funding, I think all of the puzzle pieces are out there to make that cycle work.”

Nick Brown

Nick Brown is the editor of Daily Coffee News by Roast Magazine.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Mr. Kettler should look at this simple & direct water purification system using 5 gallon buckets & terra cota biochar pots as filters.

5 Gallon Bucket Bio-Filters;

Photos & details about the CORDES facility in El Salvador by Odette Varella Milla, [email protected],

BIO-FILTER

The Biofilter is a water filtration unit made by a mixture of clay and Charred rice husk,

http://doctor-biochar.blogspot.com/2014/08/bio-filter_24.html

IDE, a big Clinton Development Initiative collaborator, has used the same technique;

Rabbit Ceramic Water Purifier

https://www.engineeringforchange.org/solution/library/view/detail/Water/S00067

Also this

Clean Biomass cooking is no small thing.

The World Bank Study;

Biochar Systems for Smallholders in Developing Countries: Leveraging Current Knowledge and Exploring Future Potential for Climate-Smart Agriculture http://fb.me/38njVu2qz

has very exacting analysis of biomass usage & sources, energy & emissions. Also for Onion farmers in Senegal and Peanut farmers in Vietnam.

A simple extrapolation made from the Kenya cook stove study, assuming 250M TLUDs, (Top-Lite Up Draft) Cook Stoves for the roughly 1 billion folks world wide now using open burning. A TLUD per Household of 4, producing 0.52 tons char/Household/yr, X 250M = 130 Mt Char/yr Showing sequestration of 130 Million tons of Biochar per year, could be achieved just from cooking.

In terms of CO2e, these 250M Households reduce 825M Tons of CO2e annually. The cascading pulmonary health benefits for woman & children is the very thick icing on this 0.825 GtCO2e Soil Carbon Cake.