Cupping is a widely used practice in the coffee industry, and while good standards for cupping exist, few companies put in the effort to rigorously determine what cupping practices will work best for their needs or even verify that their practices match standards they claim to use.

When applied to your cupping protocol, the manufacturing concept known as centerlining — which involves reducing variables and, in some instances, increasing efficiency — can allow your company to be more consistent in sample evaluation while also making it easier to distinguish among similar coffees.

First, it’s important to understand why the standards for cupping are what they are. There are mechanical considerations. For example, if the crust breaks on its own before the cupper gets to it, it’s hard to reliably judge the aroma of the coffee.

For another example, darker roasts can mask defects that you would like to detect while excessively light coffees also make it difficult to discriminate on quality. The goals of cupping play a role in determining standards, and many of the variables in cupping are standardized to accommodate a broad range. This is in part because of the huge range of equipment used by different companies in the industry with different capabilities and people with different skill in roasting samples, but also because anywhere in those ranges is good enough for basic communication through the supply chain.

While the people who write standards intended to be used across an industry need to keep those standards realistic in order for them to be widely adopted, individual companies are often in a position to set tighter process envelopes that are specific to their equipment and the skills of their personnel.

Doing this deliberately allows the creation of a standard that maximizes the chance that observed differences are the result of the coffee being different and not the result of variations in preparation. Documenting that internal standard makes it easier to ensure that the standard is being used consistently by everybody in the company.

To centerline a cupping protocol, start by identifying the variables. How is the coffee roasted? What is the coffee to water ratio used? How much time is allowed between roasting, grinding, and cupping? How is the coffee ground? What water source is used? How hot is the water? How much time is allowed between pouring water on the coffee and breaking the crust?

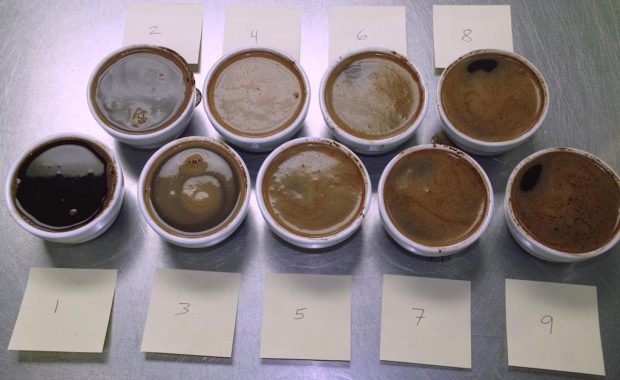

For each of these questions, it is possible to devise an experiment in which coffees are prepared identically except for a variation on a single variable. I recommend repeating these with multiple coffees. Some coffees should be chosen to represent the range of coffees you are most interested in evaluating while others should be chosen because they are similar. This allows you to evaluate how easy it is to distinguish among similar coffees in each test while ensuring that the standard set is reasonably applicable across the range of coffees you’re likely to evaluate.

When designing your experiments, make sure that you’re testing things that are easily repeatable. For example, there are many sample roasters that people are using successfully every day that have no meaningful instrumentation. Can you reliably hit certain development milestones in a tight range despite this? Maybe, but if not, it’s fine to skip the experiments on the roasting portion of the standard.

There are, however, several roasters currently available that do have adequate instrumentation and controls that are good enough to standardize a roast profile for cupping. If you have that capability, there is no good reason not to use it. If you don’t have that capability, it makes no sense to develop a roasting standard that assumes you do.

As you conduct these experiments, it’s important to document the results. This can make your standard more relevant to the tools you have available. For example, the SCAA Cupping Protocol defines the grind as one in which 70 to 75 percent of the particles pass through a 20 mesh sieve. Nobody has a grinder with a setting marked in that way and many places that cup coffee also don’t have a sieve set. By testing how your cupping sessions work with different grind settings, you can determine what setting works best for that grinder and document it in the same terms as the settings are indicated on that grinder.

You’re more likely to get everybody choosing the same grinder setting if the standard is documented as “grinder setting #5” than references to how the coffee passes through a sieve. Since grinders can get out of calibration, it may also be helpful to keep a grind sample to compare against in the future and if you do have tools to measure particle size distribution, those should still be used so you can periodically check that your documented grind setting is still producing roughly the same distribution.

Once you’ve done your experiments and documented your new internal cupping protocol, remember to keep that document up to date. If you get new equipment or perform maintenance that might affect the performance of that equipment, it’s important to review how this might affect cupping and decide if any protocol changes are needed. If so, those changes also need to be communicated to everybody involved in cupping.

This might seem like a lot of work, but the end result is that you’ll have a greater appreciation for why cupping standards are what they are and you’ll have a tighter internal standard that makes it easier for you to make appropriate decisions based on the results of your cupping. It can also be a good training exercise, and, for certain types of people, it can also be a lot of fun.

Neal Wilson

Neal Wilson has roasted coffee at Wilson's Coffee & Tea since 2000. He is an SCAA specialized instructor, a YouTuber (N3Roaster), and the author of Typica, a free program for coffee roasters.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Help me too much