In a previous guide, we covered all the main coffee plant types, such as varieties, cultivars, hybrids, landraces and more. Now that we know the important distinctions between all these plant types and how they came into being, it’s time to explore the most prominent individual varieties and cultivars.

If you’re a roaster, these are the most common names you’ll see on any seller’s offer sheet — names like Bourbon, SL28, Pacamara, Kent, or even the somewhat problematic “heirloom.” Where did they get these names? From which countries did they originate? Who are their parents? Why do roasters prize them? Read on to learn more…

Traditional Varieties

Serendipitous selections, born of circumstance or necessity

Ethiopia’s Landraces and Cultivars

While there are indeed some “heirloom” varieties still widely grown — “landrace” is gaining popularity as a more specific term for these — Ethiopia is hardly bereft of agronomy research. Critical genetic banks of arabica are kept at the Jimma Agricultural Research Center (JARC) and two fields maintained by the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute (EBI). JARC in particular has been proactive in selecting and breeding coffees for cultivation, as well.

Thus, the blanket “heirloom” designation for this origin does a disservice to the wide array of genetic variation and significant work steeped in Ethiopia’s forests and mountains. Many so-called “indigenous heirloom varieties” are in fact hybrids or selected cultivars. These are surprisingly well documented, and recently put into a concisely organized and publicly accessible format. Perhaps you’ve already picked up a copy of Getu Bekele and Timothy Hill’s work, cataloging over a hundred pages worth of coffees grown in Ethiopia. If not, I’d recommend adding it to your library.

A potted example of Sudan Rume at the Cenicafé campus in Chinchiná, Caldas, Colombia. Photos courtesy of Royal Coffee, unless otherwise noted.

Sudan Rume

As its name suggests, this selection was made from a local landrace in South Sudan’s Boma Plateau, home to one of the remaining indigenous arabica coffee forests. Kept alive as a genetic donor, Sudan Rume is a low-yielding plant regarded for its high sensory quality, though it also has moderate resistance to disease. Batian, Castillo, Centroamericano, and Ruiru 11 are all hybrids that include Sudan Rume’s genetic contribution.

Yemen’s Landraces

While Yemen does have a Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation, its efforts have not been focused on coffee cultivar breeding. Thus, the vast majority of coffees grown in Yemen are considered landraces that were “selected” at some point in unrecorded history from Ethiopia and evolved on the Arabian peninsula independently. Both Typica and Bourbon trace their lineage here, though you won’t find most Yemeni coffee farmers calling their trees by these names. Rather, the local landraces typically take the name of the region in which they are grown, such as Udain and Bura’a.

Mokha (or Mocha, Mocca, Mokka, al Mukha, etc) became common parlance for coffee from Yemen in European countries probably beginning in the 17th century. This creates a great deal of confusion, as there is also a distinct variety known as Mokha (found under the Mutations category below). However, ‘Mokha’ coffee of Yemeni origin was not a botanical term, but rather a misappropriation of just one of many port cities on the Arabian peninsula through which the trade of coffee flowed. It became a metonym for the commodity quickly despite the fact that no coffee grows in the port of Mokha.

Typica

Arabica’s first commercial variety to leave the Arabian Peninsula, Typica traces its lineage to an unknown landrace in Yemen, which grew and evolved there after originally arriving from Ethiopia likely after the middle of the 15th century. Typica was “selected” and taken to India, either by the Indian Sufi pilgrim Baba Budan or by the Dutch — merchant Pieter van der Broeke frequently receives credit for snatching a tree from Mokha and bringing it to Amsterdam’s botanical garden around 1616.

Regardless of how it arrived in western India, the Dutch took Typica from Malabar to Java at the very end of the 17th century. The first attempt in 1696 failed after flooding killed the seedlings, but the second succeeded in 1699. After its introduction in Indonesia, it thrived globally — nearly exclusively — for 150 years, making its way all around the Indian and Pacific oceans. The Dutch brought a Typica tree from Java to Amsterdam’s botanical garden, and gave another to the French royal court. These trees populated the Western Hemisphere, first landing on the islands of Martinique and Haiti and on the coastal colony of Suriname in and around the Caribbean in the first quarter of the 18th century, remaining the sole American variety until the middle of the 19th.

Morphologically, Typica is a conical tree with narrow leaves and long, narrow berries and seeds. While some growers list Jamaican Blue Mountain as a distinct variety, genetically it is identical to Typica. In Mexico, the local Typica is often called Pluma Hidalgo.

Bourbon

Arabica’s second globally cultivated variety, like Typica, Bourbon was “selected” from Yemen landraces. France targeted the island of Bourbon, now La Réunion, for coffee planting and obtained 60 trees from their agent stationed in Mokha, who was in the good graces of the Yemeni court. On September 25, 1715, the trees were delivered to La Réunion; only 20 survived the journey. By 1718, just one of these original trees remained, but colonists managed to plant 117 of its seedlings, and by the end of 1719, a few hundred trees were thriving.

This new Bourbon variety, other than the beans exported to France for consumption, would remain confined to the island until the middle of the 19th century. First brought to Brazil in 1859, it quickly gained popularity; it was more productive compared to that country’s Typica trees. Many sources speculate that Brazil’s now-famous Yellow Bourbon, first reported in 1930, is a cross with Brazilian Yellow Typica called Amarelo do Botucatu.

Standard red fruit Bourbon trees made progress through the Americas, in many places replacing the original Typica fields. French Spiritan Missionaries from Bourbon also took the tree with them to Tanzania’s island of Zanzibar and central coast town of Bagamoyo in 1868. From here, Bourbon trees would disseminate throughout East Africa, evolving into numerous local iterations and selections.

Bourbon trees generally are rounder and shrubbier in appearance than Typica. They have broader leaves and produce more spherical fruits and less ovoid seeds.

Selections

Systematic and intentional botanical choices, reproduced for distribution

Gesha

Gesha, with or without the i, begins its origin story somewhere close to the town of Gesha in remote western Ethiopia’s Bench Maji Zone. British agents picked and transported coffee from the forests around Kaffa to Kenya in 1931, and seeds from these trees were then sent to Uganda and Tanzania in 1936. A second expedition and collection was made that year, as well. The British botanist T.W.D. Blore, based in Kenya, notes the tree’s “long drooping primaries, prolific secondary growth, small narrow leaves and bronze tips.”

The seeds then made their way across the Atlantic Ocean to the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE) in Costa Rica in 1953. Researchers there targeted the selection for its resistance to coffee leaf rust. CATIE’s elevation is quite low, around 600 meters above sea level, and planting there, and shortly thereafter in Panama, brought by an agent of that country’s ministry of agriculture, was largely abandoned due to low productivity and poor quality. It’s generally accepted today that the cultivar is fickle, and that its best attributes are highlighted by a combination of elevation, rainfall, soil and nutrient composition, and myriad other environmental and horticultural factors.

Recent genetic testing by World Coffee Research (WCR) provides evidence that there are many Geshas growing that are not a genetic match to the CATIE sample. That sample, labelled T2722, is commonly referred to now as Panama(nian) Ge(i)sha due to its meteoric rise in prominence on the fields of the Jaramillo plot of Hacienda la Esmeralda in Boquete, first recapturing international attention at the Best of Panama auction in 2004.

It shouldn’t be all that surprising to hear that there are genetic discrepancies in Gesha seedlings, looking back on the cultivar’s history. Note that multiple collections were made in the field, and many different research stations, beyond those mentioned, have had their own collections since the 1950s. Gesha was gathered very near the heart of wild arabica’s naturally diverse origin, so it should come as little surprise that not all Gesha trees are a perfect match to each other.

At any rate, Gesha has invigorated the industry and placed a benchmark for cup quality not easily matched by other cultivars.

Kent

In 1911, one of coffee’s earliest known rust-resistant selections was made on Doddengooda Estate in Mysore, India, from a single Typica tree that showed an uncanny ability to withstand the fungus. Named Kent — the surname of the man who discovered it — the cultivar became popular in India, Uganda, Tanzania, and Kenya (all British colonies) in the 1920s and 1930s, and was an early ingredient in resistant cultivar “recipes,” most notably contributing its genes to Jember (S795), which is still planted widely in Indonesia. However, in the hundred-or-so years since its selection, Kent has “lost” its resistance and is no longer considered well-suited for the virulent strains of rust that have emerged in recent decades.

Java

A confusing addition to the list, Java is a selection from one or more Ethiopian landraces. Some early Ethiopian accessions made it to Java in the 19th century, but the best records indicate that what we know as Java was selected from a few mother trees in Ethiopia by the Dutch coffee researcher P.J.S. Cramer in 1928. He sent seeds to Java where the plants flourished and showed resistance to leaf rust where other arabica varieties had faltered. To this day, in Indonesia the cultivar is referred to as Abyssinia (or as cognates Adsenia or Abissinie), the name of Ethiopia at the time.

To further complicate matters, I’ve seen “Adsenia” applied to a grade or region — rather than a cultivar — in places like Sumatra, meaning you might be getting a Catimor labelled “Adsenia” because it was well-sorted. Nevertheless, true Abyssinia Java cultivar was eventually taken from Indonesia to Cameroon, and introduced to Central America as well. It bears morphological resemblance to Typica, but in fact its provenance is more direct, and in that regard it is similar to the origin story of Gesha.

SL14, SL28, SL34

These classic Kenyan specialty selections were made by Scott Agricultural Laboratories in the 1930s. Scott Labs (SL) were established in a building formerly used as a sanatorium and hospital in the town of Kikuyu, a stop along the Mombasa railway just northwest of Nairobi. Named for Dr. Henry Scott, of the Church of Scotland Mission in 1913, in 1922 it became an agricultural facility after a prominent agricultural supervisor relocated from Kabete and transferred resources from Nairobi. Coffee research, however, was not integrated at the facility until 1934. In the 1960s, Scott Labs was folded into the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization, and its work continues to this day under that moniker. There are many SL coffee breeds, but the two most popular in Kenya are SL28 and SL34, though SL14 is widely planted in Uganda as well. Many of the varieties were developed with the intention of improving resistance to drought.

SL28 predates the coffee sector’s move to Kikuyu, selected and released as early as 1931 from a bronze-tip Tanganyika (now Tanzania) drought-resistant variety. That selection was first made by A.D. Trench, the Kenya colony’s Senior Coffee Officer (who also released his own Kenya Selected varieties in the 1920s). SL28 was lower yielding and less resistant to disease than intended, but it did achieve a high sensory quality, which explains its ongoing popularity.

SL34 is a Kenyan selection, from a single tree observed in Kabete in a field labelled as French Mission, presumably Bourbon trees. It’s a bit more productive than SL28 and better suited for planting in lower elevations. Like SL28, its new growth is also bronze-tipped. World Coffee Research indicates that genetic testing of both SL14 and SL34 suggests they are closer to Typica than Bourbon, meaning the French Mission selection story might be incorrect.

Mutations

Significant morphological changes observed in the field and then isolated

Caturra, Pache, Pacas, Villalobos, Villa Sarchi

A Brazilian contribution to arabica’s American catalog, Caturra is a single-gene mutation of Bourbon, first reported in 1937 along the border of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo. It’s primary mutation characteristic is its short stature, which allows for denser planting and easier picking. It is a parent of both Catuaí and the Catimor group.

Not alone in its short stature mutation, Caturra shares genetic similarities with a number of other dwarf arabica varieties, including:

- Pacas, a Bourbon mutation first described in 1949 in El Salvador. It is named for the family that owned the farm. With Maragogipe, it is a parent of Pacamara.

- Pache, a Bourbon mutation first noticed in 1949 in Guatemala.

- Villalobos (a Typica mutation) and Villa Sarchi (a Bourbon mutation) first reported in the 1950s and 1960s in Costa Rica. Villa Sarchi is a parent of the Sarchimor group.

Mokha & Laurina

Like the dwarf mutations that result in uniquely compact, conical trees, the Mokha cultivar and Laurina are genetically very similar, though they do have some morphological differences. What they share is a little more remarkable, however: both mutations contain very low amounts of caffeine compared to traditional arabica varieties.

Mokha is a small, conical tree with very tiny cherries and seeds. It seems likely to be a Brazilian mutation, like so many others. Brazil also long transshipped (or wrongly labelled) some of its coffee as “Mokha,” further obfuscating an already befuddling distinction. Yet it’s very likely that as a result of its name, the Mokha cultivar gained more global popularity than Laurina.

Known also as “Leroy” or “Le Roy” (maybe the name of the person who selected it), and “Bourbon Pointu” (literally “pointy Bourbon”), the name Laurina likely stems from the tree’s resemblance to the bay laurel, the source of your soup’s bay leaf. Laurina evolved independently on La Réunion, a conical shaped tree with very pointy seeds. These phenotypic expressions might lead you to believe that the tree is related to Typica somehow, a claim perpetuated by an important genetic academic resource published in 1951 called simply Advances in Genetics. Others have proposed it may have hybridized with locally indigenous Coffea mauritiana, which also assumes a conical shape. However, recent genetic testing has confirmed that Laurina is nearly identical to Bourbon, so researchers have concluded that the single surviving tree that spawned La Réunion’s population had embedded in its genetic code a recessive trait that emerged spontaneously on the French-occupied island in the Indian Ocean.

Maragogipe

Sometimes spelled with a “y” instead of an “i,” Maragogipe represents the other side of the mutation spectrum, at least when it comes to size. This spontaneous Typica deviant is giant, the tree and its fruits and seeds being about twice the size of the average arabica. This gigantism, however, is combined with some less desirable attributes like slow cherry maturation, low yields, and a reputation for slightly inferior quality. It takes its name from the town Maragogipe in Bahia, Brazil, where it was first discovered. With Pacas, it’s the other parent to Pacamara.

Hybrids

Spontaneous natural crosses and lab-engineered mashups

The Timor Hybrid

After the Eastern Hemisphere’s coffee trees began dying in droves in the late 19th century, smitten by the first global coffee leaf rust epidemic, robusta (C. canephora) was introduced to islands in the Pacific Ocean. The improbable occurred on Timor, now split between Indonesian sovereignty and that of the independent nation of Timor-Leste. There, arabica spontaneously cross-bred with robusta, creating a new interspecific hybrid.

Arabica and robusta’s union is a singularly unusual feat, due to the fact that the tetraploid (four sets of chromosomes) arabica in theory shouldn’t be genetically compatible with its diploid (two sets) ancestor — robusta is acknowledged as one of arabica’s parents, the other is C. eugenioides. So in a sense, you could consider this hybrid a kind of backcross, 100,000 years in the making.

Regardless, the Timor Hybrid — often called “Tim Tim” and sometimes abbreviated HdT for “Hibrido de Timor” — became a regional favorite shortly after it was first observed in the early 20th century. It now provides the baseline genetic source for many disease resistant arabica cultivars, the most common of which are collectively referred to as Catimors and Sarchimors.

Catimor & Sarchimor

First created in Portugal at the Centro de Investigação das Ferrugens do Cafeeiro (CIFC), the first of many iterations of Catimors were created by hybridizing a hybrid. The Timor Hybrid was crossed with Caturra, the dwarf Bourbon mutation, and first introduced to Brazil in 1967. There are many strains of Catimor that have been created since with different individual plant parents and generational selections. Thus, Catimor refers to a group of distinct cultivars, rather than a single variety. Popular Catimors include Costa Rica 95 and Cat 129, both trees that retain Caturra’s short stature and while improving its leaf rust resistance and yield.

Similarly, Sarchimor is a group rather than an individual genetic selection. The Sarchimor group is a cross of Villa Sarchi and the Timor Hybrid. Among the more popular are IAPAR 59 and Obata, both bred for rust resistance in Brazil, but in separate research labs, and Centroamericano, an F1 Sarchimor hybrid crossed with Sudan Rume.

Despite their robusta heritage, both Catimor and Sarchimor groups are classified genetically as arabica, and are widely planted throughout the world.

Ruiru 11 & Batian

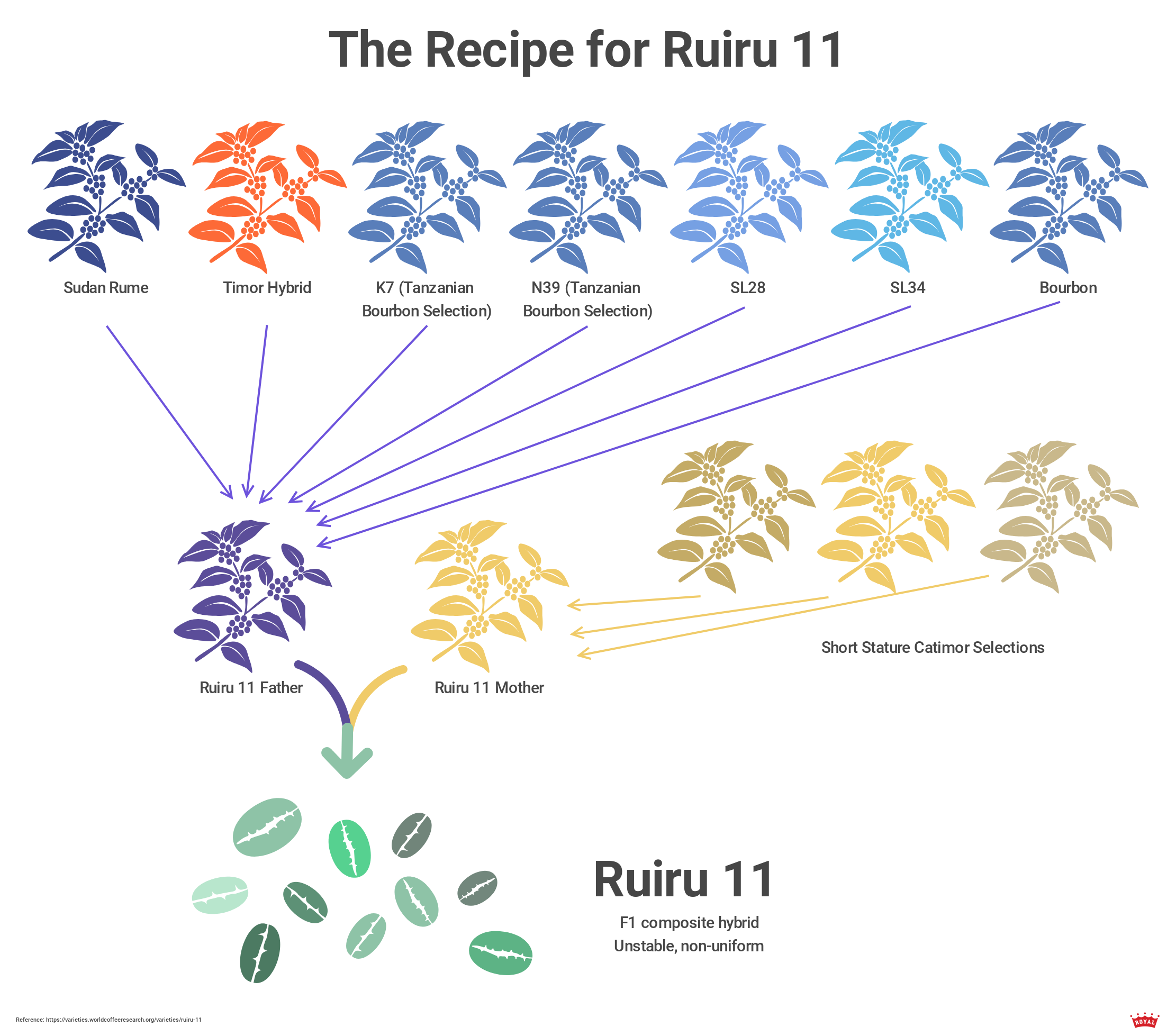

Kenya’s Ruiru 11 belongs in the Catimor group, but it is singled out here for a few unique characteristics. Although it’s considered an F1 hybrid, it is quite a bit more complicated than a cross of two traditional varieties. Ruiru 11’s father and mother (more on this in the next paragraph) were themselves complex hybrids, using varieties including SL28, SL34, Sudan Rume, a few Bourbon selections, and a number of Catimors with the intention of achieving a blend of CBD (Coffee Berry Disease) resistance, compact stature, high yields, and cup quality.

In Ruiru 11’s case, it’s entirely appropriate to specify the parent gender for a very practical reason. Pollination between the two complex parents of Ruiru 11 occurs manually. The recipes for creating the father and mother tree are distinct. The tall tree is always bred as the male, donating the pollen to the female, bred to be short in stature. The seeds that grow from this process are non-uniform, and are blended and distributed as a composite cultivar.

Named for the research station it was bred in, Ruiru faced two major challenges after its release. First, the manual pollination makes breeding time consuming, and supply failed to keep pace with demand. Secondly, with regard to cup quality, sweetness and character were overlooked in favor of acidity and body. Thus, specialty cuppers frequently rate it lower overall than SLs.

In response, Batian was released in 2010, using Ruiru’s same genetic material, with a focus on cup quality and a short span between planting and harvest. Most Batian trees have a sizable fruit load by their second year, and a full harvest at year three. Batian was selected from F5 generations of Ruiru parent material that omitted the dwarf characteristics. The name Batian was taken from the highest peak of Mount Kenya, which itself takes its name from a prominent Masai leader.

Colombia, Tabi, Castillo, Cenicafé 1

In Colombia, a 6 cent per-pound tax on exported coffees funds the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros (FNC), one of the world’s largest and most high-profile coffee organizations. Laser-focused on improving volumes and prices country-wide, the FNC has been developing and releasing productive coffee varieties for decades under their Cenicafé research division, established in 1938. Using Catimor’s HdT x Caturra recipe as a blueprint, Cenicafé first created the Colombia variety as an F5 composite, and released it in 1982. Seeking to improve flavor, Typica and Bourbon replaced Caturra in the cross for the Tabi cultivar, released in 2002.

Cenicafé’s early rust resistant varieties were longstanding and somewhat popular alternatives to the country’s aging stock of Typica and Caturra. However, Colombia captured the world’s attention in 2005, with the release of Castillo. That cultivar is now the most commonly grown coffee plant in the country, thanks in part to heavy marketing, national taste competition victories, and subsidized seed pricing.

Castillo’s benefits include high yields and disease resistance, but its raison d’etre is its multi-line composite of 5th generation (F5) breeding that allows for genetic diversity sufficient to resist rust and other diseases holistically within a single field of trees. On a typical monoculture Caturra farm, in the increasingly likely event of a strain of “super-roya,” the entire field would succumb to such a monstrous predator. However, only part of the Castillo grove would be susceptible because — despite being 100% Castillo — there are actually five or so thoroughly unique genetic compositions in each bag of seeds. Additionally, Castillo has been divided into 16 “regional” quality variations in addition to a “general” profile.

Cenicafé has now released an eponymous cultivar, Cenicafé 1, which stays true to the Catimor composite, multigenerational selection formula. This newest release meets or exceeds Castillo cup scores and yields, with the added benefit of improved CBD resistance and larger screen size, which should result in more Supremo grades and higher prices for producers.

Mundo Novo

After Bourbon was introduced to Brazil, it eventually cross-pollinated with Typica, producing a naturally occurring hybrid first observed in 1943 in Sao Paulo state. Two separate selections were made for distribution, the most recent in 1977. It’s a tall tree with good yields, but its range is mostly confined to South America.

Catuaí

Catuaí springs from a Brazilian cross of Mundo Novo with Yellow Caturra. It was developed in the 1940s but not released into the public domain until 1970s. It retains the short stature of its Caturra heritage, and is resistant to wind. It’s also a quite productive tree with the caveat that it requires an above average amount of fertilizer.

Pacamara

Pacamara is a Salvadoran cultivar, released in the 1970s but worked on for more than 30 years prior to that at the Genetic Department of the Salvadoran Institute for Coffee Research (ISIC). Despite accounting for less than 1% of El Salvador’s coffee plants, Pacamara has developed a cult following among specialty roasters. Interestingly, the quality report that accompanied its release recommended processing it as a natural for best results. An odd hybrid, Pacamara’s parents are the dwarf Bourbon Pacas and the giant Typica Maragogipe. Pacamara retains the large leaf and bean size of Maragogipe.

Monica Valdivieso and her father Ricardo stand in the midst of a Pacamara tree on their farm Finca Leticia in Apaneca, El Salvador

Jember

Known by a plethora of names, including S795 and Linie S (the “S” just stands for “selection”), the Jember cultivar is widely used in Indonesia. Jember is the name of a regency in East Java, and the location of a research station through which it was distributed, but the cultivar was developed in India. Bred from two resistant parents, Kent and S228, it is a disease resistant hybrid. While Kent is a resistant Typica selection, the other half’s stoic designation is a wildly underwhelming name for an extraordinary spontaneous interspecific hybrid of West Africa’s native Coffea liberica with Ethiopia’s indigenous arabica.

Chris Kornman

Chris Kornman is a coffee romantic and educator, and a quality specialist with a history of indiscreet coffee buying, roaster fires, ill-advised travel, and oversharing. He is the author of Green Coffee: A Guide for Roasters and Buyers and regularly contributes coffee-related disquisitions to publications worldwide.

Comment

7 Comments

Comments are closed.

I’d like to learn more on the growing aspect of the coffee beans

I would like to know how to tell apart Arabica varieties from Robusta ones. I am afraid it is not mentioned in this very interesting paper.

Furthermore, I am in East DR Congo (South Kivu) and the coffees here were left from Belgians during the 1960’s and the yield has decreased very drastically. Is there any cultivar suit for the climate change we are encountering in the region?

Not inclusive, but very informative. However, there are other varieties. I am fascinated by the ‘hybrid ‘ idea, although sensibly narrated, it cuts short on the geographic reference.

If the idea is to instigate the innovation thought in coffee roasting, it is a great work.

Thank you,

It is learning and experience sharing page of innovative ideas of modern coffee technology!!

Curious if you have heard of Liberica. I’ve heard it’s used for root stock, but I’m currently roasting it with excellent results. Enjoyed your article.

Good Global Coffee information

Good information but not enough coz other varieties are left out.