Coffea arabica has evolved dramatically over the course of history, rising from humble under-canopy trees growing wild in the forests of Keffa in western Ethiopia and South Sudan’s Boma Plateau into globally traded agricultural product. As with the difference between a Valencia and a Blood orange, the specific type of coffee can impact a plant’s morphology (physical appearance), annual yield, resistance to disease and, of course, flavor.

The following two terms, often used interchangeably in coffee, are actually completely distinct in the language of horticulture: variety and cultivar. I was lucky to consult with Izi Aspera, who helped to clarify the two for me:

Varieties often occur in nature and most varieties are true to type. That means the seedlings grown from a variety will also have the same unique characteristic of the parent plant. Cultivars are not true to type, they are usually heavily controlled hybrids… and must be propagated by cuttings, tissue culture, and grafting. These terms are both very divisive in describing how a plant grows.

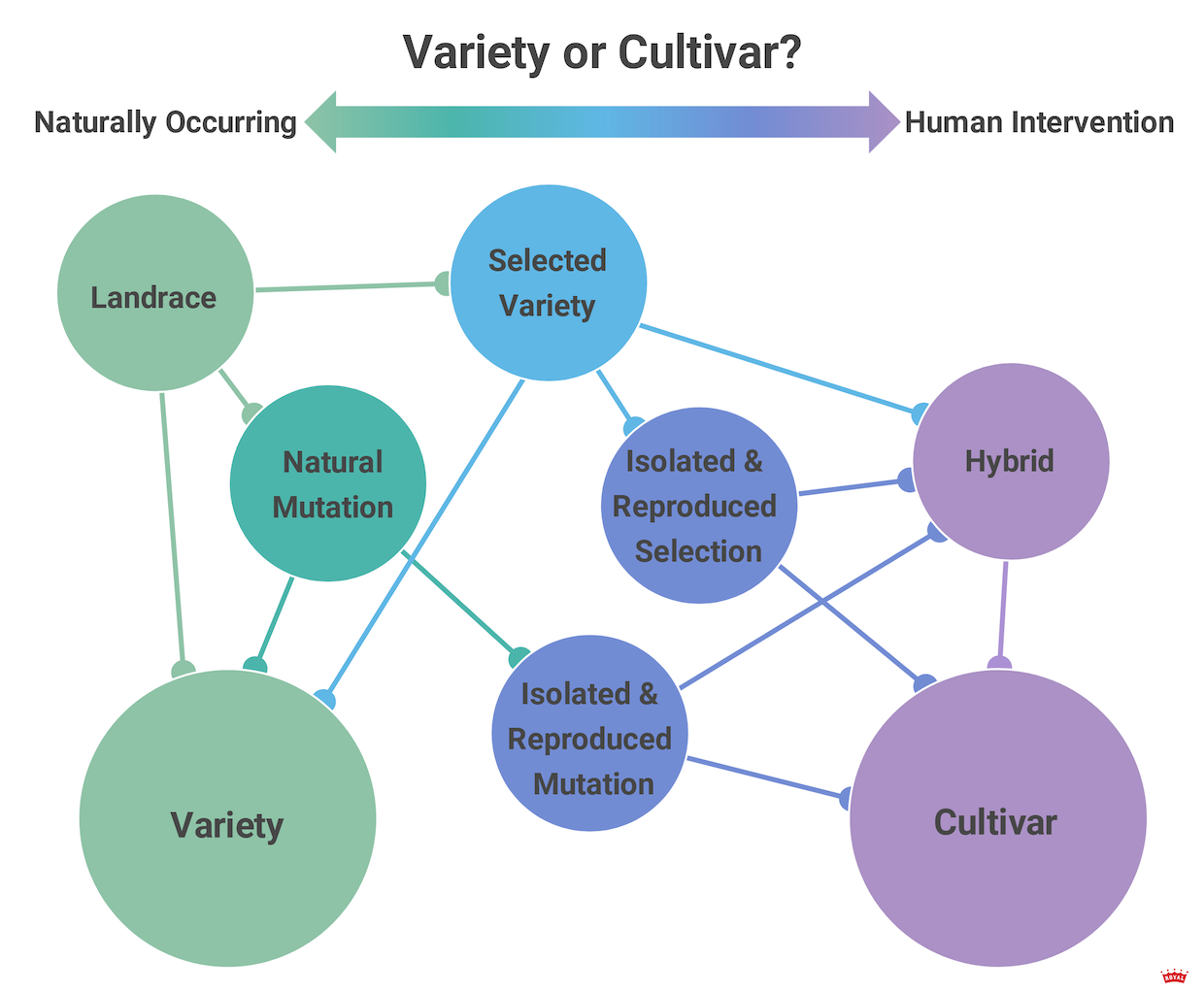

Both variety and cultivar are a taxonomic rank below species, but a variety occurs naturally, and clones itself readily from seed. Typica and Bourbon are examples of varieties. Conversely, a cultivar must be propagated by human intervention. Catimor and Castillo are examples of cultivars.

The word cultivar is just a mashup of “cultivated variety,” coined by Cornell University’s Liberty Hyde Bailey in 1923, who proposed “cultivar, for a botanical variety, or for a race subordinate to species, that has originated under cultivation; it is not necessarily, however, referable to a recognized botanical species. It is essentially the equivalent of the botanical variety except in respect to its origin.”

Varietal has often been used informally — and sometimes formally — in the coffee community, usually interchangeably with “variety,” but the two don’t really mean the same thing. Variety is a botanical term, and a noun. Varietal was born as an adjective meaning “having the characteristics of a variety.” Nowadays, usage of varietal as a noun occurs most frequently in the wine world, referring to the beverage made from a single botanical variety. Pinot Noir, for example, is a variety of grape, but a varietal of wine. To put it another way, you can drink a varietal that has the characteristics of the variety you’ve planted and harvested. It’s a relatively minor distinction, but one that makes a big difference if we’re trying to be precise. You’re drinking a varietal cup of Bourbon, which was picked from a Bourbon variety tree.

A wild variety, like those found in coffee forests across Ethiopia, can be referred to as a landrace, a term that indicates a few important distinctions. Landraces are generally considered domesticated, but locally adapted, and distinct from any formal breeding or selection. Thus both a wild forest coffee and a traditional home garden in Ethiopia could be growing a landrace variety.

Oftentimes landraces, natural variation(s) in a field or offspring in a breeding program are chosen for further breeding, cloning, or wider dissemination. This process is called selection. Kent was selected from a single rust-resistant tree on a plantation in India; Gesha was selected from a limited number of seeds from a wild population in Western Ethiopia. Sometimes when making selections for a gene bank or breeding program, botanists will borrow the library science term accession, which simply means a single, unique sample.

The term heirloom has often been applied to Ethiopian forest coffees, and more broadly to global varieties like Typica and Bourbon. Many plant growers now use heirloom as a marketing term, though the word more directly relates to family artifacts, passed down through generations. As a result, the agricultural definition of heirloom is both contested and inconsistent. In one sense, it can broadly be used to refer to any variety that has not crossed with another strain. Since arabica can reproduce through open-pollination (i.e., by the natural spread of pollen from a flower’s stamen to stigma by a bird, the wind, or by hand), Bourbon, Typica, Caturra, and Mokha could all be considered a type of heirloom variety.

However, more strictly, most plant breeders and gardeners use “heirloom” to refer to non-commercial fruits and vegetables, and frequently mark a point in history — usually World War II — as the cutoff. In the 1940s and 50s, monoculture commercial breeds became increasingly important in global agriculture. Thus, an heirloom plant is often a private, home-garden reaction against this type of macro-farming, frequently passed generationally like a family heirloom. In this sense, relatively few coffee varieties would qualify.

Ultimately, heirloom seems insufficiently precise and far too confusing to be of practical use when discussing a variety of coffee. In its place, our best options remain landrace for locally adapted varieties in the field in Ethiopia and Yemen. Outside of these countries, when describing Bourbon, Caturra, or Mokha, for example, variety is the most precise term. In place of heirloom, using the word “traditional” or “legacy” might better convey the historic importance of these strains.

Caturra and Mokha are also mutations — genetic anomalies that change something significant about a plant’s nature. In the case of Mokha, the genetic mutation resulted in very small spherical berries and seeds. In a sense, nearly all naturally occurring varieties began as a mutation that was passed down through generations. Many cultivated mutations are also selected at some point in their history — isolating, preserving, and reproducing their unique genetic code.

For more than a century, Typica was the exclusive variety grown worldwide outside of Ethiopia and Yemen. Bourbon, genetically very similar to Typica, provided little relief to the relative monoculture. Furthermore, arabica can self-pollinate, meaning its seeds will often be clones. This bottleneck of genetic diversity created some significant problems, including susceptibility to disease and climate change. One way to improve diversity is to cross-breed varieties and species.

In contrast to traditional varieties and mutations, a hybrid refers to a unique plant bred from a cross-pollinated or lab-induced blend of at least two distinct genetic parents. Naturally occurring hybrids are not rare for coffee, since cross-pollination occurs readily with other nearby trees. Hybrids created in labs are commonly bred for disease resistance or improved yield, for example. Because hybrids contain unique genetic material contributed from two separate populations, they are said to have “hybrid vigor,” or increased genetic diversity. By selecting a particular accession for a unique genetic trait, a hybrid can be crafted to retain desirable characteristics of its parents and propagate cultivars.

Hybrids themselves have a number of unique subcategories. Intraspecific hybrids are bred from parents of the same species. Mundo Novo is a spontaneous intraspecific hybrid of two traditional arabica varieties, for example. On the other hand, interspecific hybrids are a cross of multiple species. The Timor Hybrid is an interspecific hybrid of Coffea arabica and robusta (C. canephora). Interspecific hybrids can also be referred to as introgressed, meaning new genetic material was introduced. Castillo and Ruiru 11 are examples of introgressed varieties — both are arabica plants that contain a little genetic material introduced from robusta.

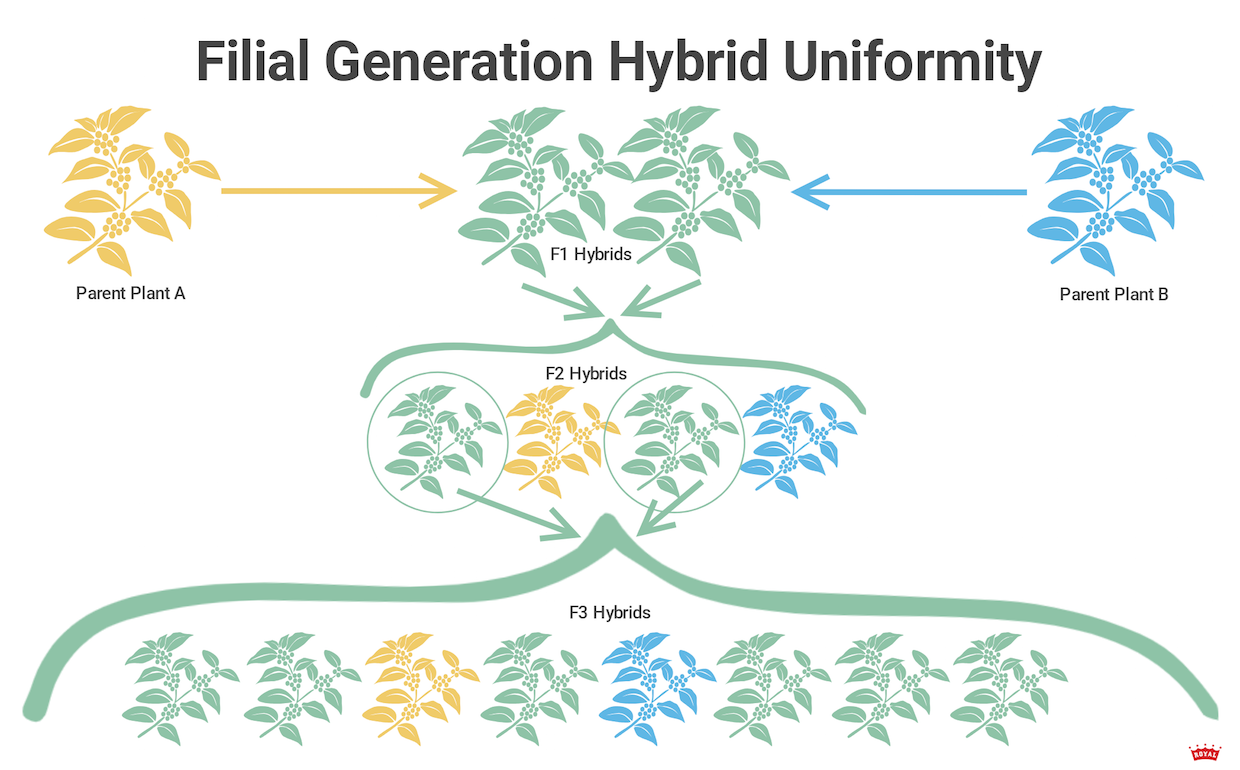

A hybrid of two distinct varieties will result in relatively uniform offspring. Dominant genes will express in most of this first generation. Breeders refer to this first crossed generation as filial, and designate each generation with a number. Centroamericano is an F1, a first filial generation hybrid, meaning it is a direct descendant of its two parents, a Sarchimor and Sudan Rume. However, if the parent plants are themselves hybrids, the F1 generation siblings might result in a composite with complex genetic variation built into the fabric of the cultivar’s genetic code. Castillo and Ruiru 11 are both composites — the seeds in a bag of Castillo will not produce identical trees.

F1 plants are not stable for reproductive purposes. Breeding two identical F1s together will result in a genetic rearrangement, where a sizable minority of the offspring will display a mix of traits from recessive genes or revert to expressions of the original parents. The more genetic variation in the parent plants, the less stable the F2 offspring will be. Creating a stable offspring usually requires selecting and breeding down to the fourth or fifth (F4 or F5) generations. For many coffees, fifth generation (F5) are usually considered relatively stable, but still not quite 100 percent. Castillo is an F5, or fifth filial generation plant.

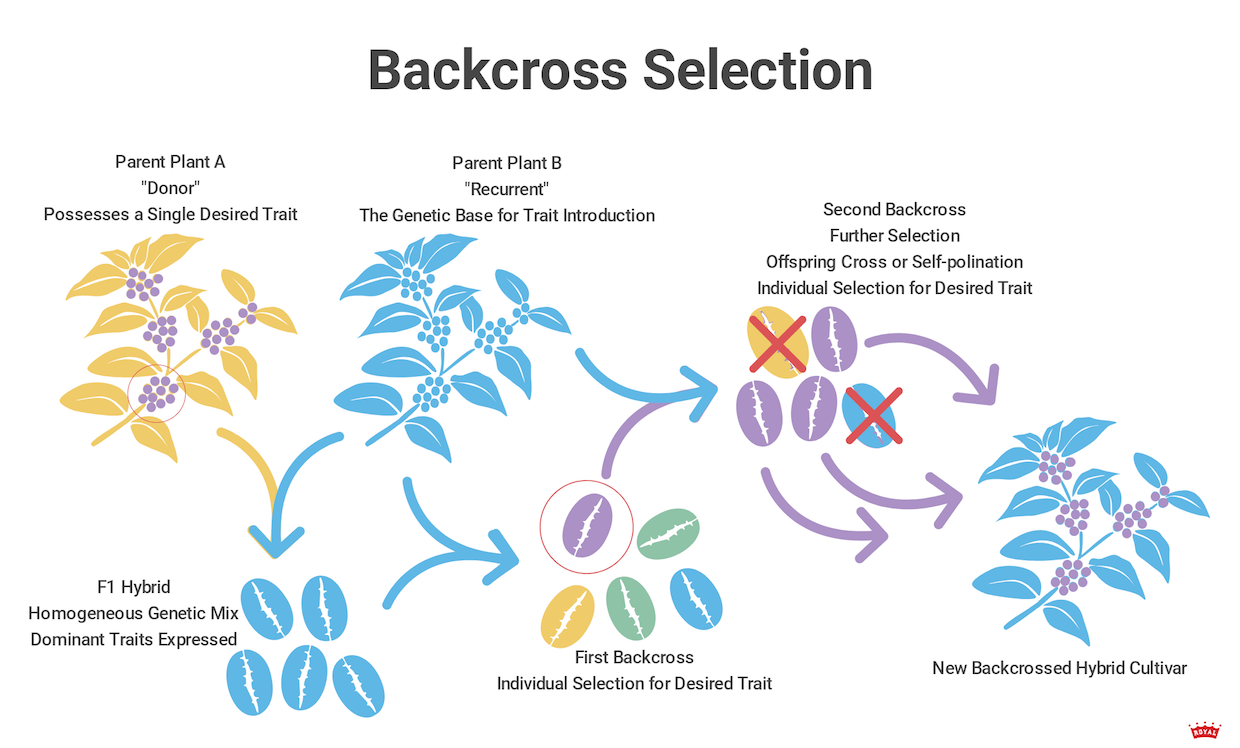

Lab-crafted hybrids are often backcrossed with a parent plant, to reinforce a particular genetic trait like disease resistance or seed size. In a typical backcrossing scenario, Parent Plant A will have a characteristic that the breeder wants to introduce to the makeup of Parent Plant B. An F1 hybrid of the parents will be created, and that hybrid will then be backcrossed in with Parent B. The next offspring will be selected for the gene marker from Parent A, then backcrossed again, repeating the process, occasionally self pollinating the generations, until the seedlings are a stable, uniform cultivar that expresses mostly Parent B’s characteristics, but with the new Parent A gene included.

Varieties and cultivars, even ones that that are supposed to be the same (like two F1 hybrids from the same parents) can still adapt differently to local environmental conditions. Recent work by University of Michigan alum and Coffee Manufactory Sustainability Director Stephanie Alcala showed three distinct phenotypes (observed characteristics like appearance and growth patterns) in Gesha trees on Hacienda Esmeralda, including a dwarf. This adaptability is often referred to as plasticity.

Now that we understand these different plant types, we can use this terminology to better understand the history and prominence of some of the most common varieties, cultivars and hybrids. Stay tuned for the next guide!

Chris Kornman

Chris Kornman is a seasoned coffee quality specialist, writer and researcher, and the Lab & Education Manager at The Crown: Royal Coffee Lab & Tasting Room.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

every one of chris’ articles seem to be a jewel for the coffee industry at large. in many cases i have found no more reputable, detailed, and easy to understand sources on the subjects about which he writes. it’s as if he does all the necessary research that so many writers don’t have the time to do, and distils it all into an article that we do have time to read, as dense and rich as it may be. i suggest taking notes on these articles, as i always do. this one is absolutely no exception.