Guatemalan coffee has long held a place of honor among specialty coffee roasters. Regional names like Antigua, Cobán, and Huehuetenango are familiar to many, and are frequently synonymous with exceptional quality.

The country’s history with coffee runs deep; most historians credit it as the first country in Central America to grow the crop. While 18th century exports from Central America were largely dominated by sugarcane, indigo, and cochenal (a short-lived, insect-derived dye), Spanish Jesuits cultivated coffee in Antigua prior to 1767, and perhaps as early as 1730 )p 30-31).

Throughout the 20th century, Guatemala was Central America’s leading exporter, and, despite being passed for that title by Honduras in 2011, the country continues to rank in the top tier of global coffee exports by both weight (10th in 2016) and value (14th in 2018).

Like most Central American countries, Guatemala was rocked by the coffee leaf rust epidemic in 2012-2013. It has also been a region of focus as increased public attention is drawn to the intersection of immigration and the historically low coffee prices of 2018-2019.

I’ve been thinking a bit about the way that coffee stories are told, specifically by roasters and importers, and how we can be better at amplifying the narratives told by others rather than speaking over them — or worse, taking the words out of their ownership completely and reframing them as our own.

In light of this and as we head into a new decade, I reached out to two coffee professionals in Guatemala, both of whom are connected deeply to production and trade, to hear in their words what the future of coffee holds in the country. I think their perspectives offer some sobering truths about the changing nature of specialty coffee production, but also a lot of hope for the future.

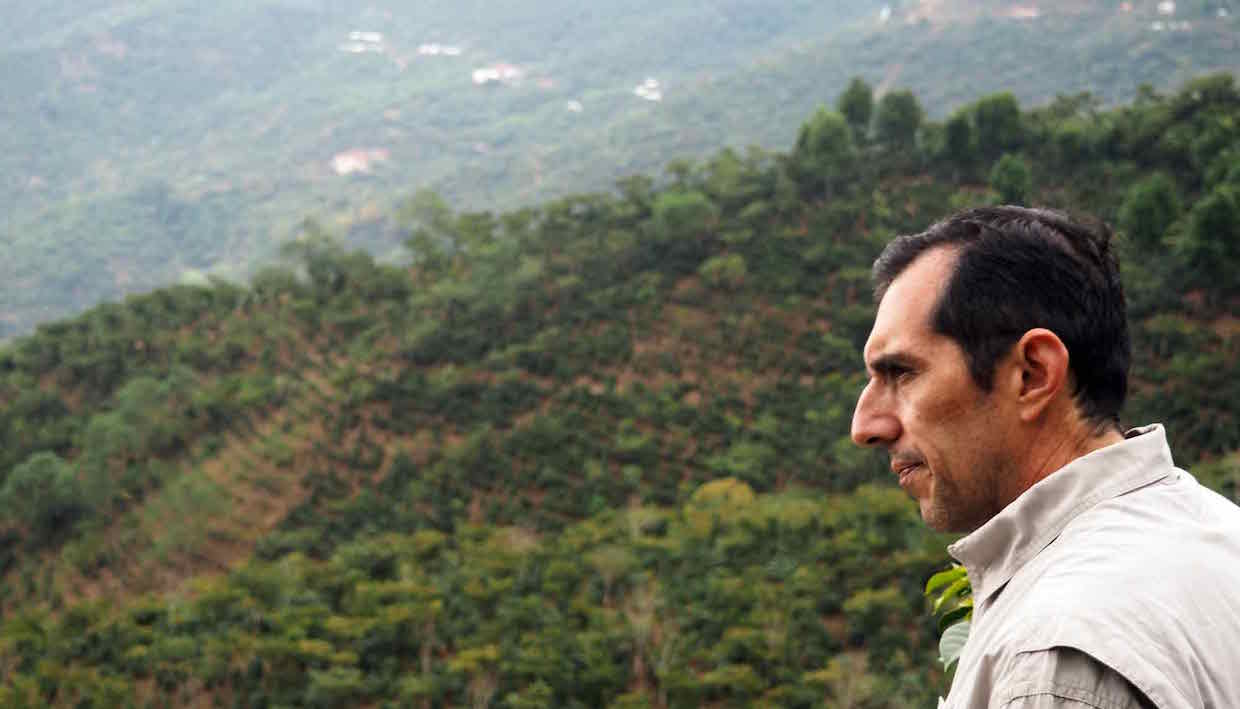

Jose Alejandro Solis Chavez is a third-generation coffee producer who manages production on his family farms Finca Huixoc and Injertal in Huehuetenango near San Pedro Necta. His farms are equipped with climate stations and his data collection has provided tools to both Guatemala’s Anacafe and to the UK-based Climate Edge firm. He is a long-term supplier to Royal Coffee, and I must confess I probably prod him far too frequently with questions about his thoughts on topics ranging from climate change to rust to improved cultivars.

Melanie Walleska Herrera Moreira works in Antigua with Luiz Pedro Zelaya Zamora’s Bella Vista organization as a salesperson, relationship manager, and producer outreach partner. She holds degrees in Agribusiness from Zamorano University in Honduras, and International Trade, and Supply chain management from AGEXPORT/Universidad de San Carlos in Guatemala.

(The interviews below have been lightly edited and condensed for clarity. Many thanks to Mayra Orellana-Powell for the introductions.)

Chris Kornman: What do you see as the biggest challenges for coffee in Guatemala, particularly as we look to the future?

Melanie Herrera: Weather variation: temperature, rainfall, natural disasters, and greater incidence of plagues and diseases. These aspects make the sector very risky, so access to funds are very complicated to get. It limits the ability to invest, even more so for small producers, who have nothing to give as a guarantee to get loans.

Guatemala has been consistent in quality and has always excelled in this matter, but because of that we have forgotten about productivity. With low prices for arabicas, robustas are starting to draw attention for business opportunities in our zones.

CK: In what ways has coffee production needed to adapt over the last decade or so?

Alejandro Solis: If you mean adapting to the change in climate, we have mostly adapted in a few different ways: First, looking for varieties which can have resistance to rust and still have an acceptable cup quality. Second, we have, on Huixoc and Injertal, started to diversify our shade cover by planting a native oak species which can grow much higher than our shade trees and provide a higher shade cover. We also manage our shade cover more carefully, especially if we are under the effects of “El Niño.” We try to keep our soil covered all the time to prevent soil temperature in the soil to get to high.

I continue to gather weather data with my meteorological station. I am sending soon new data to Peter Baker [of Climate Edge] for him to analyze. Weather has become another risk factor which we have to follow.

MH: Most of the new changes come from the need to adapt to changes due to climate change. I would say the most critical thing now is considering irrigation, which is a heavy investment, especially when the prices of coffee are so low. But in the long run, producers who switch to irrigation will be the ones in advantage.

CK: Can you comment on the changes you see as the coffee producing world has entered the digital age?

MH: First, communication. With social media stories are easier to tell and reach more people. This opens up opportunities and closes a big gap for marketing and communication that existed for many years.

Data collection in all parts of the coffee chain has improved: from producing countries — small producers and estate farms — to mills, to exporting companies, to importing companies, to intermediaries, to final consumer.

With climate change and all it involves, coffee growers have to rely on technology to be able to produce more and better tasting coffee using less productive land, less water, and less resources than before — or at least with less opportunity to control as temperature rises, long droughts or excess of rains in places, etc etc. This leads to precision crop management that can improve the economic and environmental sustainability of crop production: more precise info on inputs required specifically per unit of production; needs of irrigation with real time information for efficient use of water; drones for fertilizing; apps for control of plagues and diseases. And furthermore, breaking the normal models of planting and by this I mean the exploration of using different spacing between plants and rows for a more efficient use of land. The flow of information is amazing!

AS: Definitely, I see a lot of benefits from the digital age. Information is more readily available on agrochemical products, new processing machinery and, more important, about the market trends and futures price market. Sometimes there is too much info and I barely have time to see a small part of all this.

I am not a user of social media, but I wanted to provide information about what’s going on in the farm to the roasters that buy our coffee from Huixoc and Injertal. So I got help from my daughter-in-law and started using social media (Facebook) to present to roasters what’s going on here at the farms. I would like roasters who cannot come to the farm to get a feeling of what’s going on here. However the best way to connect with roasters is when they come and visit. Social media presents only a front page of the farm but a visit really gives the person the knowledge of how through our work we provide some excellent coffee.

CK: What is your relationship like with local roasters and cafes in Guatemala?

AS: 100% of our coffee is exported. Specialty coffee here in Guatemala has grown significantly in the last five years, but it is still very small and the quantity consumed is still very low. Also, in times of low market prices, local cafes can get coffee at almost commercial values, which makes you favor the export of your coffee.

MH: Local roasters in specialty here have grown in Guatemala, especially in Guatemala City and more urbanized areas, but also in rural areas. People have found good business opportunities with coffee: Small cafes, coffee education, consumer awareness of why a good cup of coffee would be more expensive, and all the labor (and faces) it involves.

Bella Vista sells green coffee to local business but we focus mostly in selling roasted coffee. As for the coffee from the plot we own with my brother and sister in law, we deliver mostly to Bella Vista. I get to keep some. Bella Vista roasts it for us and we sell it locally. With the profits we sponsor girls so they can go to school. I had the privilege of getting high end education through scholarships. And I personally know what education can mean to a girl’s life. So we want to support education to the best that we can.

Chris Kornman

Chris Kornman is a coffee romantic and educator, and a quality specialist with a history of indiscreet coffee buying, roaster fires, ill-advised travel, and oversharing. He is the author of Green Coffee: A Guide for Roasters and Buyers and regularly contributes coffee-related disquisitions to publications worldwide.

Comment