Portland, Oregon, played host to the biennial ASIC conference, which was held in the United States for the first time since 1991.

Baristas, roasters and cuppers, myself included, are quick to invoke the contributions of art and science in our field. Growing, processing, roasting, brewing, and sensory analysis all require a fair degree of scientific rigor before they meet the touch of a skilled craftsperson.

Specialty coffee professionals, I’d wager, usually fall a little right-brained-of-center at this particular intersection. I’ll include myself in this camp. My undergraduate degree is in language arts, and my coffee skills have been honed as an apprentice in the craft rather than as an academic. Yet my title reflects that I’m a “lab” manager, and it’s true that I endeavor to bring a fair degree of scientific exactness to my work with basic steps like blind cuppings and employing the scientific method, for example.

It became apparent at the Association for Science and Information on Coffee (ASIC) biennial symposium in mid-September in Portland, Oregon, however, that I was in way over my head when it came to the hard sciences. ASIC has held their conference roughly every other year since 1963 as a way to bring together specialists in the fields of science and technology as they pertain to coffee.

Roast Magazine Publisher Connie Blumhardt with Alex Brooks of Scott Laboratories (left) and Marcus Young of Boot Coffee. Photo by Roast Magazine.

I was thoroughly impressed by the level of rigor brought to the podium, and thoroughly humbled as a coffee professional whose career in science probably will need about eight to 10 more years of formal education before I can converse with any fluency.

So, with the aspect of an eager pupil, I took copious notes, and here I’ll attempt to distill some of the event’s many highlights. All research summarized below is the intellectual property of its respective participants and funders. I can claim no part in it other than minor rephrasing and dissemination.

Day One

Caffeine Metabolism

Monday’s first keynote, presented by ASIC Director Astrid Nehlig, focused on caffeine metabolism. Caffeine can be found in the brain within as little as two minutes after consumption, and while there’s a wide array of genetic variability, age does not factor into differences in caffeine absorption rates.

Pregnancy, obesity, and alcohol consumption can increase the half-life (normally 2.5 to 5 hours), while smoking increases the clearance rate. Interestingly, there are some genetic associations with predisposition to caffeine-induced anxiety, but this group doesn’t tend to consume less than any other group.

Dr. Nehlig closed her presentation noting that the study of caffeine’s effect on the human body is “still in a non-advanced stage, even though caffeine is one of the most studied and consumed substances in the world.”

Biomarkers in Coffee

Civet coffee was shockingly quick to make an appearance at the event. Dr. Emmanuel Garcia presented findings on biomarkers in coffee, as a way to verify authenticity. He found that there were about 130 protein distinctions between green and roasted coffee, just 19 between Liberica and Robusta species (apparently the cats don’t like Excelsa, and there wasn’t any Arabica around), and a mere nine between civet and non civet coffee. These differences were far more present prior to roasting, and some of the changes in civet coffee might be related to pathogen presence in the cat poop.

Dr. Garcia then made an interesting observations I hadn’t considered. He noted the concerns with animal abuse, but mentioned that if civet coffee were to lose value or be outlawed, farmers may opt to kill the cats as they would be seen as farm pests in competition for the harvest.

Coffee Fermentation Biology

Two researchers from Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium, Sophia Jiyuan Zhang and Florac De Bruyn, working in conjunction with Nestle in Ecuador and China, presented some fascinating research on the biology involved in coffee fermentation.

One of their most surprising findings to me was that lactic acid bacteria far outnumbered any other population, including yeasts, in any coffee fermentation type they observed. This seems to run contrary to previous research published that found yeasts to be more important. They also observed that “fermentation effects can be tempered by long duration of soaking” before drying the coffee — a technique currently employed in many locations in the coffee-growing world. Even though soaked coffees lost up to 10 percent of their weight compared to non-soaked coffee, the researchers found an increase in overall flavor intensity and quality rating. This could provide a scientific basis for that qualitative improvement in the post-fermentation soak.

The team established a processing hierarchy, one that could differentiate the effect on flavor intensity in the cup. Here are the results, from most impactful to least: processing type (natural vs. washed, etc.), fermentation duration, pulped vs. demucilaged, and, lastly, the post-fermentation soak.

Farm Management

Monday afternoon was dedicated to sustainability and farm management. The afternoon keynote speaker, Uganda-based agronomist Dr. Laurence Jassonge, provided an excellent perspective based on her experiences working with smallholders who have limited resources. Many of the most costly elements involved in farming include chemical inputs (fertilizers, pesticides, etc.) and labor. Working in a region highly susceptible to climate change where farmers typically do not receive exceptional prices for their coffees — regardless of whether it’s Robusta or Arabica — presents a singular challenge: achieving sufficient yields for survival.

Dr. Jassonge’s four-step proposal prioritizes efforts for smallholders like weeding, planting shade, controlling pests, pruning, and mulching over expensive and intensive solutions like irrigation, fertilization, herbicides or other chemical controls. While it’s common to consider these inputs as necessary, her work has shown major improvements can be achieved with lower cost efforts prior to expensive investments like chemical fertilization.

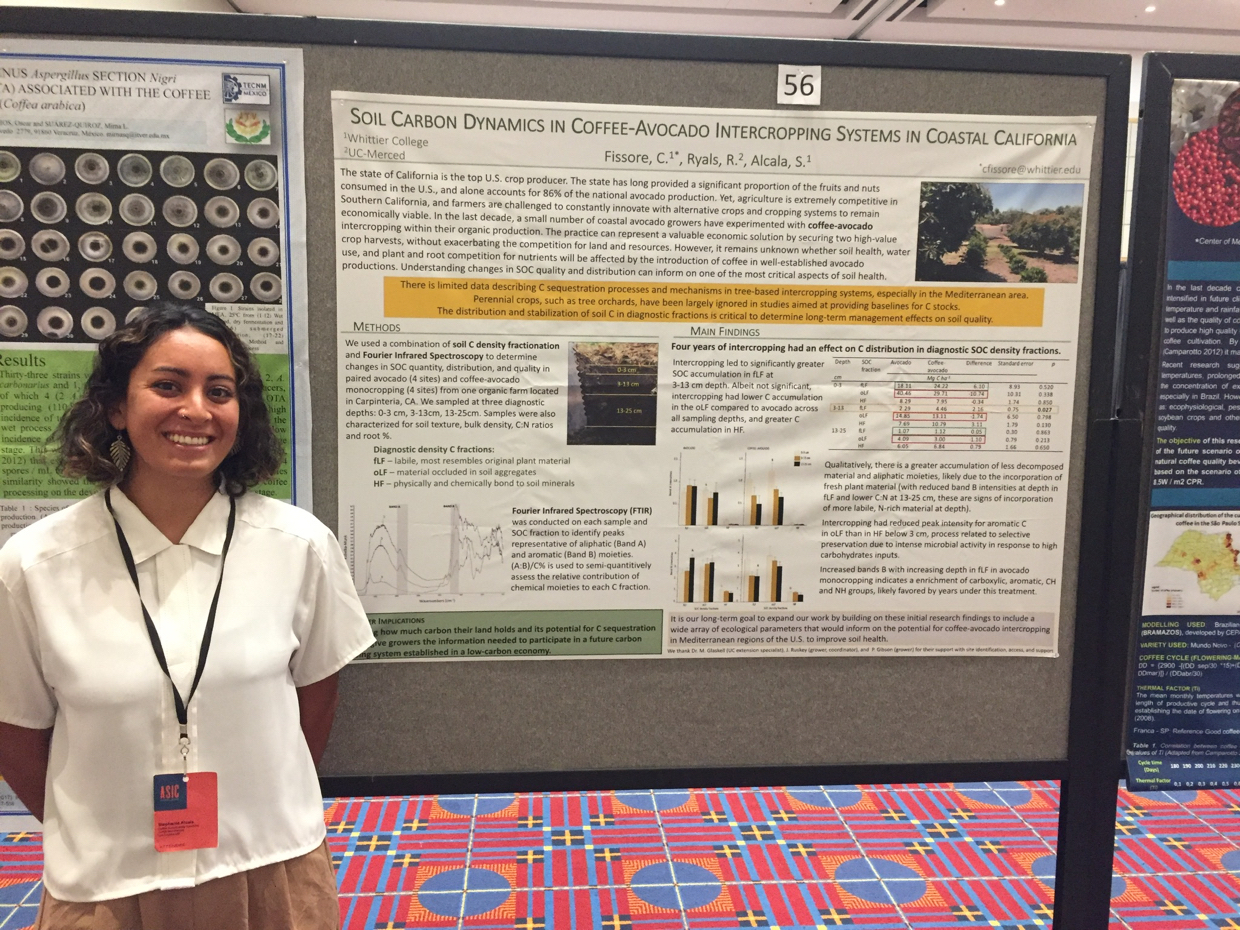

Outside of the seminars, researchers presented additional work. Here is Re:co Fellow and SCA LEAD Scholar Stephanie Alcala with her poster on coffee-avocado intercropping in California. Photo courtesy of the SCA.

The Number of Coffee Farms

Next, David Browning, the CEO of Enveritas, a nonprofit with the stated mission to end poverty in the coffee sector by 2030, displayed an impressive use of empirical and statistical analysis to provide a new estimate of the number of coffee farms in the world.

The popularized number, 25 million, was first published in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with ambiguous terms and no published methodology. Enveritas covered ground in 20 countries, consulted with 80 established institutions in the coffee sector and conducted over 20,000 interviews. Their final estimate of the number of coffee farms in the world was 12.5 million, nearly half of which are located in just three countries: Ethiopia, Uganda, and Indonesia.

Climate Issues

Much of the afternoon focused on climate issues. The scientific community concerned with coffee production is hardly in the business of attempting to establish causes of climate change, or attempting to confirm or deny its existence. The issue is already a confirmed reality in many areas, and as a result research is focusing on multi-pronged approaches to alleviate, renew, or resolve issues related to loss of arable lands for coffee.

Christian Bunn of Colombia’s International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) painted a complex picture of global trends in climate affecting production. While macro agricultural trends are unshifted in the short term, local trends are much easier to observe, the starkest being an estimated 11.5 percent drop in production in Ethiopia. However, production losses also observed in places like Guatemala and Vietnam are largely offset in the short term by annual increases in production in Brazil.

Cooperative Farming

In a project funded by Starbucks and implemented under the joint efforts of World Coffee Research (WCR) and Guatemala’s Anacafe, a study was conducted on the profitability of cooperative farming. The results were absolutely disheartening.

Based on data provided by the farmers about the cost of production and the prices paid for their coffee, there was a 0 percent chance of profitability, and when a fair rate for the time and labor of the farming family was accounted for, there was a 50 percent chance of net loss. The only way for a farmer to profit was to take off-farm jobs, or to improve the productivity by replanting with hybrid cultivars resistant to rust and capable of higher yields. In light of the current market, one can easily imagine the unsustainable prices leading to farmer attrition for more profitable endeavors.

Soil Science

Offering a fascinating take on soil science, Dr. Andrew Margenot of UC Davis attempted to dispel the romantic myth of volcanic soil. He noted that less than 1 percent of the earth’s non-ice surface is covered in volcanic soil, and that, in fact, more of it exists in the U.S. Pacific Northwest than in the tropics. He also noted that the presence of a volcanic slope does not necessarily equate to the presence of volcanic soil, and demonstrated this using survey of 11 different sites on a single volcano, each with a diverse, highly variable soil profile.

[Editor’s note: DCN will have more of Chris Kornman’s coverage of the ASIC conference later this week.]

Chris Kornman

Chris Kornman is a seasoned coffee quality specialist, writer and researcher, and the Lab & Education Manager at The Crown: Royal Coffee Lab & Tasting Room.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Will ASIC have any of these presentations or links to presenters’ research?