Between 1931 and 1944, Brazil literally burned 78.2 million bags of exportable coffee. That equates to an astounding 10.3 billion pounds of coffee, an amount that would take 3.7 years for Brazilians to consume these days.

Coffee has been an inextricable part of of Brazilian daily life since the 19th century, with important social ties. Coffee is so intertwined with Brazilian culture that in Brazilian Portuguese, the meal known as “breakfast“ is often referred to as “Café da Manhã,” or “coffee in the morning.”

So how did Brazil get to the point of burning this beloved and important material at its harbors, warehouses and farms? The answer lies in the political and economic significance of coffee on Brazilian life and livelihoods.

Historical Context

The history of burning coffee involves some historical context going back long before the first match was lit in 1931.

By the 1870s, Brazil was beginning to separate from the monarchy on its road to forming a republic, which officially came with with the 1889 military coup that overthrew Emperor Dom Pedro II.

Helping to articulate this political movement were large coffee producers and landowners who were seeking compensation for the abolishment of slavery as well as subsidies to bring in European immigrants for coffee plantation labor.

The term of the country’s second civilian president, Campo Sales, began in 1898, and with it came a regime that ultimately became known as the “República do café com leite,” or, “coffee with milk.”

This name was derived from the activities of the economically and politically dominant, and most populous, states at the time: Minas Gerais (milk) and São Paulo (coffee).

In this time, the political strength large coffee landowners led the government to encourage more cultivation, make credit lines available and create institutions to promote coffee growing, research, and commerce.

By 1906, an overabundance of coffee had caused coffee prices to drop. This prompted the governors of three coffee-producing states to engage in a valorization effort, using international loans to purchase surplus coffee stocks and thereby stabilize or increase international market prices.

This political and economic balance continued for decades, with Brazil dominating the world’s coffee production. At the same time, it was common practice for coffee crops to be stored for years, since concepts about quality had not evolved to today’s standards.

1929 Economic Crash

In 1929, the Great Depression severely affected the Brazilian economy, which was heavily reliant on coffee exports. Around that time, more than 50% of the value of exported goods from Brazil was in coffee, as compared to about 2.7% today.

The United States was by far Brazil’s largest export market for coffee at the time, and the U.S. stock market crash and subsequent loss of businesses reduced total Brazilian coffee exports and value for years.

At the beginning of 1929, a bag of coffee in Brazil was worth 200,000 Réis in the national currency; yet by then end of of the year, the same bag was worth just 10% of that.

The crash was one of myriad factors that led the country in 1930 to a military coup, which overthrew the president and his successor — putting an end to the “republic of café au lait.”

Getúlio Vargas took over power, and at first sought to break government ties with large rural coffee growers, but their influence remained strong.

However, the economic balance remained delicate. Up until the crash, Brazil’s leaders held the belief that its agricultural strength in coffee, cocoa, cotton and rubber would create a kind of eternal bond with the country’s longtime trading partners, the U.S. and Europe.

Yet the economic crash proved that belief wrong. Some historians have called the Brazilian economy at the time the “dessert economy”, since many of these were not associated with essential goods. Also at this time, export costs were rising, and other countries began investing in coffee production.

Meanwhile, decades of influence from large rural producers in Brazilian politics ended up de-incentivizing industrialization in favor of rural development. In short, commodities were sold for export while manufactured products were imported.

Let’s Burn

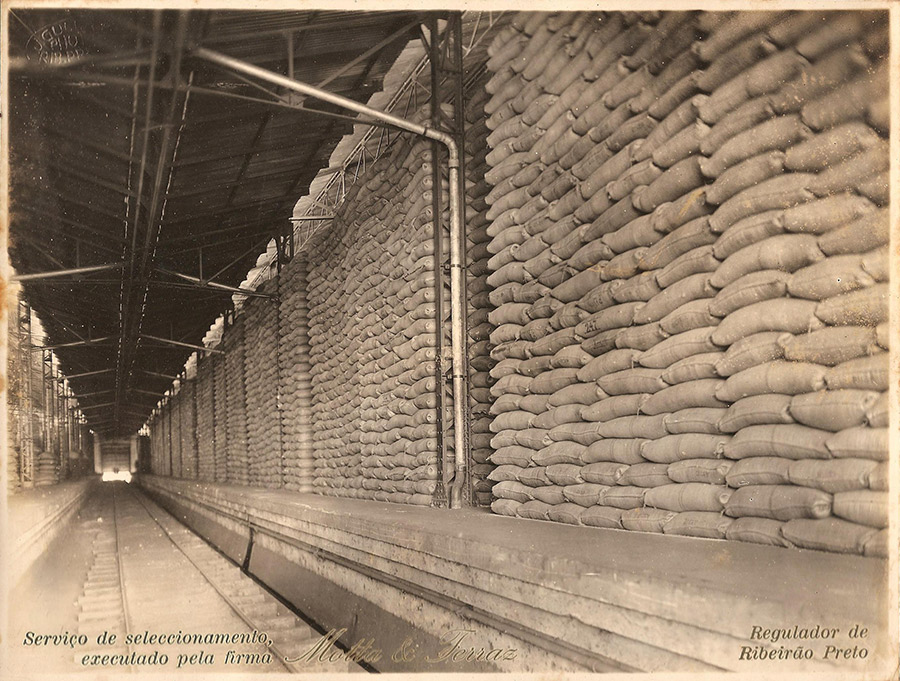

With the export market collapsing, fields filled with crops and sacks of coffee piled up in warehouses from previous crops, prices naturally crashed.

The total economy was still very coffee-based for exports, so the government under Getúlio opted to increase national customs duties and buy the stored coffee to burn it.

A commission of coffee chain members was created to make decisions, draw laws and oversee the destruction of the beans. At first, the idea was to destroy low-grade coffee, then the older coffee inventory; yet soon even quality new crop beans were also destroyed.

In theory, this would increase the value of the product on the international market by reducing supply and storage costs, which were largely financed by foreign loans. The burning of stocks was not a unanimously popular decision, ultimately led to a new finance minister, Oswaldo Aranha, who moved forward with the program in 1931.

In that year, approximately 12% of the stocks were burned. By 1937, a whopping 70% of the annual stockpile was set ablaze. On average, 27% of annual stocks were destroyed from the years 1931-44.

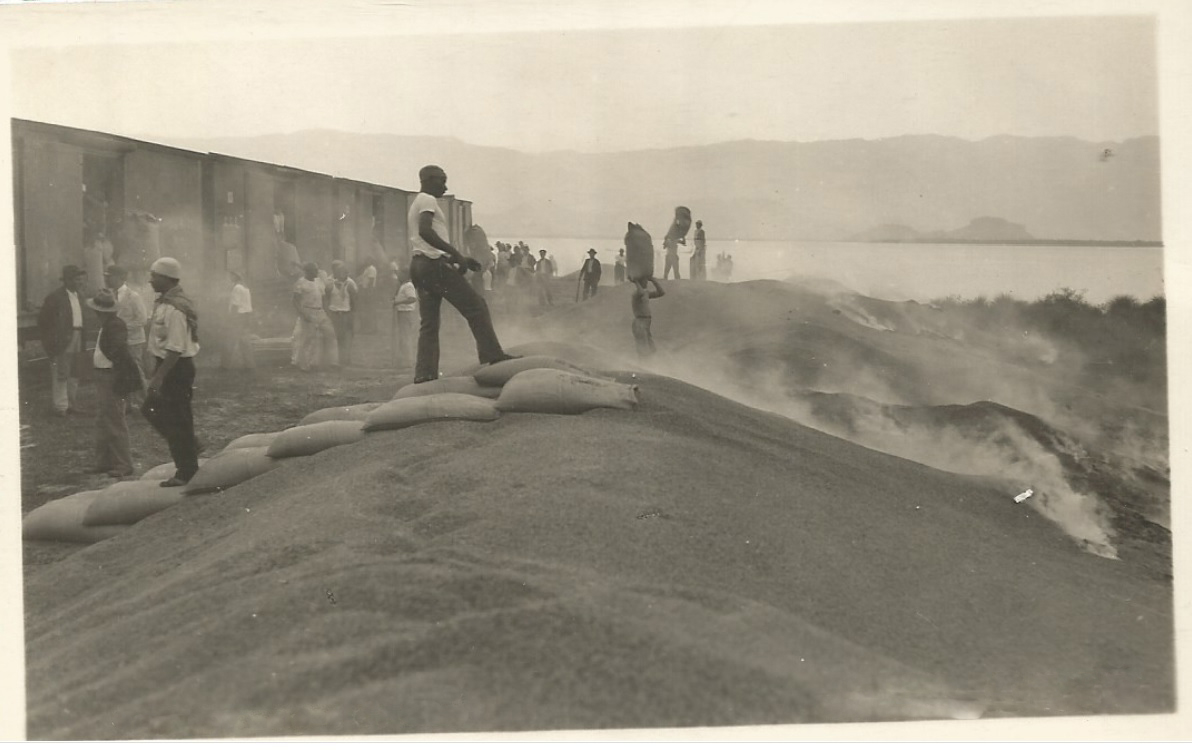

The coffee burning cycles took place mostly in the major seaport city of Santos, where currently more than 75% of all coffee still leaves Brazil to this day.

Newspapers at the time reported on the smell of burnt coffee that was carried by the wind up and down the coast of the state of São Paulo. Huge clouds of coffee smoke could be witnessed from kilometers away.

While destruction captured the headlines, preventing production also became a reality.. For five years beginning in 1931, producers were de-incentivized by a new tree tax.

In 1932 a national Coffee Stabilization Council was created to deal better with all the coffee-related issues, although international relations were strained as charges of anti-trust violations and “racketeering” came forth as a result of the stockpile burning.

Eventually, the volume of coffee sent to the fires was so great that port workers began to throw beans into the sea to reduce stockpiles. Some people then began to collect this “marine coffee” before drying it, bagging it, then reselling it — a crime.

So as not to go completely to waste, coffee earmarked for destruction was also used as an experimental fuel source in some factories and industrial boilers.

A 1932 a newspaper account detailed an experiment in which 2,912 kilos (6,420 pounds) of coffee were to fuel a steam locomotive. The green coffee fueled the furnace for two hours while moving the 610-ton train.

In Hindsight

We can now look back on this as a fascinating time in Brazilian coffee history — a kind of one-time experiment — although it had very real implications.

Many economists and historians have speculated that the market would have naturally regulated itself as time wore on after the 1929 economic crisis.

All the coffee destroyed did not generate export taxes, however small those may be. The cost to the Brazilian government was immense. Farmers were paid but many of them went bankrupt anyway as prices remained low for years as many bore debt and had little access to credit.

At the time, a reduction in domestic supply may have seemed like an attractive option for longer-term price relief. However, it is likely one more example that there are no easy solutions for many of coffee’s most complex problems.

The extreme price volatility spurred by recent frost events that unfortunately have affected thousands of producers in Brazil is another example of why rash market decisions should not be made. While the market requests immediate answers and action, the interests of coffee producers and the sector as a whole are best addressed through careful consideration and remediation based on actual conditions on the ground.

To quote American essayist H.L. Mencken, “For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.”

Jonas Ferraresso

Jonas Leme Ferraresso holds a degree in agronomy from São Paulo State University (UNESP). He has worked as a coffee farmer and as a Agronomist (Boa Esperança Coffee Farm), as a Roaster (Artesan Coffee Solutions), as a cupper and roaster (Amparo Rural Union), and as a consultant. He is based in Serra Negra, São Paulo, Brazil.

Comment

1 Comment

Comments are closed.

Drink TEA !!!! Coffee has so many health benefits and detriments as well,but tea is a meditative ritual,cleansing,or sweetened,or flowered &flavoured. Show me the coffee ceremony,or the mediation while making coffee,the ritual& wellness on its myriad forms.& The green matcha,now sold at some auctions or stamped in blocks with real gold dynasty stamps. Drink tea. You will get more than a buzz. You will get a spiritual experience. Unless you just want a lovely strong Indian chai with honey&milk- go for it,or a southern iced sweet tea&lemon. Or one of my favourites- a green tea vodka martini!